41 min read

Network Capacity Planning Models

Introduction

Network capacity planning represents one of the most complex and critical challenges in modern telecommunications infrastructure. As networks evolve to support unprecedented data volumes, driven by artificial intelligence, autonomous vehicles, Internet of Things deployments, and ultra-high-definition media streaming, the mathematical models and optimization techniques required to ensure efficient, reliable, and cost-effective capacity allocation have become increasingly sophisticated. This advanced technical analysis examines the state-of-the-art in network capacity planning models, focusing on the mathematical foundations, algorithmic approaches, and industrial implementation strategies that define excellence in this domain.

The challenge of capacity planning has transformed from a periodic infrastructure exercise into a continuous, data-driven optimization problem. Consider that in 2025, a single autonomous vehicle generates more data per hour than 3,000 smartphone users did in 2020. This exponential growth in data consumption, combined with the heterogeneous nature of modern network traffic—ranging from latency-sensitive real-time applications to massive bulk data transfers—requires planning models that can simultaneously optimize for multiple competing objectives while operating under strict physical, power, and economic constraints.

Traditional capacity planning approaches relied on historical traffic analysis and manual forecast models updated quarterly or annually. These methods proved adequate when network growth followed predictable patterns and service requirements remained relatively static. However, the contemporary network environment demands fundamentally different approaches. Modern capacity planning must integrate real-time network telemetry, machine learning-based traffic prediction, multi-layer optimization across optical and packet layers, and dynamic resource allocation mechanisms that can respond to changing conditions within seconds or minutes rather than months.

The mathematical foundation of modern capacity planning traces back to Claude Shannon's seminal work on channel capacity, which established the theoretical limits of information transmission over noisy channels. Shannon's formula, C = B log2(1 + SNR), provides the fundamental bound on achievable capacity as a function of available bandwidth and signal-to-noise ratio. While this elegant expression captures the essence of the capacity-SNR relationship, practical network capacity planning requires extending these principles to account for wavelength division multiplexing, spatial division multiplexing, nonlinear optical effects, amplifier noise accumulation, and the complex interplay between modulation format selection, forward error correction overhead, and achievable spectral efficiency.

This deep dive examines network capacity planning from multiple perspectives. We begin with the rigorous mathematical foundations, including Shannon capacity bounds, generalized signal-to-noise ratio (GSNR) based capacity prediction models, and the statistical frameworks required for forecasting traffic demand with quantifiable confidence intervals. We then explore advanced optimization algorithms, including linear programming formulations for multi-commodity flow problems, integer programming approaches for discrete resource allocation, and metaheuristic techniques for solving NP-hard network design problems. The analysis extends to multi-layer network optimization, where decisions at the optical transport layer must be coordinated with routing and wavelength assignment in the packet layer to achieve globally optimal resource utilization.

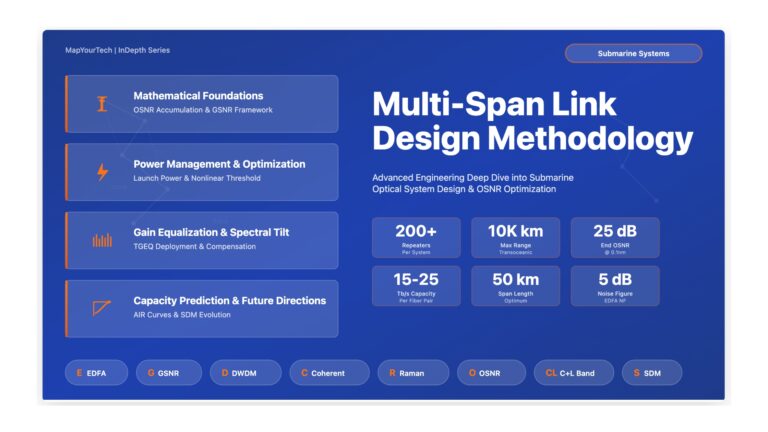

Submarine cable systems provide particularly illuminating case studies for capacity planning at scale. These systems, which carry over 99% of intercontinental data traffic, must be designed to operate reliably for 25 years while accommodating continuous technology evolution through open cable architectures. The capacity planning challenge for a transpacific submarine cable exemplifies the complexity of modern network design: with distances exceeding 10,000 km, hundreds of optical amplifier repeaters deployed on the seafloor, power budgets constrained by available feeding current, and capacity requirements measured in hundreds of terabits per second, the optimization problem involves thousands of interdependent design variables and constraints.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning have emerged as essential tools in modern capacity planning. Neural network models trained on historical traffic patterns can predict future demand with accuracy exceeding traditional statistical methods. Reinforcement learning algorithms can discover optimal resource allocation policies through interaction with network digital twins. Graph neural networks can process network topology information to identify bottlenecks and recommend targeted capacity upgrades. The integration of AI into capacity planning workflows represents a paradigm shift from human-driven, periodic planning cycles to continuous, automated optimization.

The industrial implementation of capacity planning models must balance theoretical optimality with practical constraints. Real networks operate under diverse regulatory requirements, must integrate equipment from multiple vendors with varying capabilities, face labor and materials cost structures that vary geographically and temporally, and must maintain service continuity during upgrades. Capacity planning tools used in production environments typically employ hybrid approaches combining rigorous mathematical optimization for offline strategic planning with heuristic algorithms and rule-based systems for real-time operational decisions. The ability to rapidly evaluate "what-if" scenarios, perform sensitivity analysis on key assumptions, and generate actionable implementation plans distinguishes effective capacity planning platforms from academic exercises.

Throughout this analysis, we maintain a focus on practical applicability while not shying away from mathematical rigor. Each major concept is illustrated with worked examples using realistic parameters drawn from contemporary network deployments. Mathematical formulations are presented with clear definitions of all variables and assumptions. Where multiple approaches to a problem exist, we provide comparative analysis highlighting the trade-offs between computational complexity, solution quality, and implementation requirements. The goal is to equip senior engineers and network architects with both the theoretical foundations and practical insights needed to design and optimize world-class communication networks.

Scope and Applicability: Universal Principles with Submarine Cable Examples

The capacity planning principles, mathematical foundations, and optimization techniques presented in this analysis apply universally to all optical fiber networks, whether submarine or terrestrial. Shannon's capacity theorem governs all communication channels regardless of their physical location. Multi-commodity flow optimization works equally well for metropolitan fiber rings and transoceanic cables. Machine learning traffic forecasting doesn't distinguish between data crossing the Atlantic Ocean or crossing a city. The fundamental mathematics of network capacity planning is environment-agnostic.

However, you'll notice this article draws heavily from submarine cable system examples. This pedagogical choice is deliberate and offers several advantages for learning. Submarine systems present mathematically cleaner scenarios because their constraints are well-defined and fixed: you have exactly X watts of power from shore feeding equipment, precisely Y kilometers of distance with repeaters every Z kilometers, and a specific number of fiber pairs that cannot be easily changed. This clarity of constraints allows us to focus on core optimization principles without the operational complexity that terrestrial networks introduce through their greater flexibility.

Terrestrial networks face different practical constraints. Power is rarely the limiting factor since grid electricity is available at every amplifier site. Instead, terrestrial planners optimize for right-of-way costs, real estate footprint in dense urban areas, spectrum efficiency in environments with multiple competing operators, and the ability to incrementally upgrade infrastructure as technology evolves. Terrestrial networks typically plan on five to ten year horizons with multiple technology refresh cycles, whereas submarine cables must be designed for twenty-five year operational lifetimes. These differences affect implementation details and optimization priorities, but the underlying mathematical frameworks remain identical.

As you work through the examples, recognize that when we analyze a 10,000 kilometer submarine cable with 200 repeaters and power budget constraints, we're illustrating principles that scale and adapt to terrestrial networks of any size. The power allocation optimization for submarine systems has its terrestrial analog in spectrum allocation optimization across metropolitan wavelength-division multiplexed networks. The GSNR-based capacity prediction model works whether light travels through fiber on the ocean floor or through conduits beneath city streets. The AI-driven traffic forecasting techniques apply to any network carrying variable data loads. Think of submarine examples as case studies that make abstract mathematical concepts concrete and measurable, providing a foundation you can apply to whatever network environment you encounter in practice.

1. Mathematical Foundations and Shannon's Theorem

1.1 Shannon Capacity Bounds and Information Theory

Claude Shannon's 1948 mathematical theory of communication established the fundamental limits of reliable information transmission over noisy channels. The Shannon-Hartley theorem states that the maximum channel capacity C, measured in bits per second, for a continuous channel with bandwidth B hertz and signal-to-noise ratio SNR is given by the elegant formula presented in the visualization above. This theorem provides both a theoretical upper bound on achievable data rates and practical guidance for system design.

The profound implication of Shannon's theorem is that arbitrarily low error rates can be achieved at any data rate below the channel capacity through the use of sufficiently sophisticated error correction codes. Conversely, no coding scheme, regardless of complexity, can reliably transmit information at rates exceeding the Shannon limit without introducing errors. This establishes a fundamental trade-off between transmission rate, error probability, and required signal quality that governs all communication system design.

Shannon-Hartley Theorem: Detailed Formulation

For a continuous-time channel with bandwidth B and additive white Gaussian noise:

C = B × log2(1 + SNR)

Where:

C = Channel capacity in bits/second

B = Available bandwidth in Hz

SNR = Signal-to-Noise Ratio (linear, not dB)

Converting SNR from dB to linear:

SNR_linear = 10(SNRdB/10)

Spectral Efficiency (bits/s/Hz):

η = C/B = log2(1 + SNR)

For Dual Polarization (modern coherent optical systems):

CDP = 2 × B × log2(1 + SNR)

The factor of 2 accounts for independent data streams on

X-polarization and Y-polarization transmitted simultaneously

Practical Example: 100 GHz channel with 25 dB OSNR

B = 100 × 109 Hz

SNR_linear = 10(25/10) = 316.23

C = 100 × 109 × log2(1 + 316.23)

C = 100 × 109 × 8.308

C ≈ 830.8 Gb/s (theoretical maximum)

In practical optical communication systems, the achievable capacity falls short of the Shannon limit due to several factors. Forward error correction introduces overhead that reduces the net information rate relative to the symbol rate. Modulation formats must operate with finite constellation sizes, and digital signal processing algorithms have computational complexity limits. Guard bands between wavelength channels reduce the effective bandwidth utilization. Nonlinear optical effects introduce signal-dependent noise that violates the additive white Gaussian noise assumption underlying Shannon's theorem.

1.2 Generalized Signal-to-Noise Ratio (GSNR) Model

For wavelength division multiplexed optical systems, particularly submarine cable systems operating over thousands of kilometers with hundreds of in-line amplifiers, the Generalized Signal-to-Noise Ratio provides a more practical capacity prediction framework than direct application of Shannon's theorem. GSNR accounts for the accumulation of amplified spontaneous emission noise through the amplifier chain while maintaining a linear, additive noise model that enables tractable system design calculations.

The GSNR model partitions the end-to-end signal quality into contributions from different subsystems: the transmitter's optical signal-to-noise ratio, the cable's accumulated ASE noise, and the receiver's implementation penalties. This decomposition enables open cable architectures where submarine cable suppliers can specify cable GSNR independent of terminal equipment, allowing terminal equipment vendors to optimize transponder designs to extract maximum capacity from a given cable GSNR.

GSNR Calculation for Submarine Systems

End-to-end GSNR combining multiple noise sources:

1/GSNRtotal = 1/GSNRTX + 1/GSNRcable + 1/GSNRRX

Cable GSNR for N repeaters with identical EDFAs:

GSNRcable = Pch / (N × NASE)

Where:

Pch = Channel power per wavelength (W)

N = Number of repeater amplifiers

NASE = ASE noise power per amplifier (W)

ASE noise power calculation:

NASE = NF × h × ν × (G - 1) × Bref

Where:

NF = Noise figure of amplifier (linear)

h = Planck's constant (6.626 × 10-34 J·s)

ν = Optical frequency (Hz)

G = Amplifier gain (linear)

Bref = Reference bandwidth (typically 12.5 GHz)

Practical Example: 10,000 km transatlantic cable

Repeater spacing = 50 km

N = 200 repeaters

Pch = 0.5 mW per channel

NF = 5 dB (3.162 linear)

G = 17 dB (50.12 linear) compensating fiber loss

NASE = 3.162 × (6.626×10-34) × (1.94×1014) × 49.12 × (12.5×109)

NASE ≈ 2.5 × 10-7 W

GSNRcable = (0.5×10-3) / (200 × 2.5×10-7)

GSNRcable = 10 (10 dB in 12.5 GHz reference bandwidth)

Converting GSNR to Shannon capacity estimate:

Assuming GSNRtotal ≈ GSNRcable = 10 dB

Symbol rate = 64 GBaud

SNRlinear = 10

η = log2(1 + 10) = 3.459 bits/s/Hz

CShannon = 64 × 3.459 ≈ 221 Gb/s per carrier

With 100 WDM channels:

Total Cable Capacity ≈ 22.1 Tb/s (theoretical)

Practical with overhead ≈ 15-18 Tb/s

The GSNR framework enables powerful system design optimizations. Submarine cable designers can adjust repeater spacing, fiber type, amplifier noise figure, and channel power to maximize cable GSNR subject to power feeding constraints. Terminal equipment designers can select optimal modulation formats, baud rates, and forward error correction schemes to achieve target bit error rates at the available GSNR. Network operators can forecast available capacity upgrades by comparing terminal equipment capabilities against measured cable GSNR.

1.3 Spectral Efficiency and Modulation Format Selection

The spectral efficiency, measured in bits per second per hertz, represents the amount of information that can be transmitted per unit of bandwidth. Higher spectral efficiency allows more data to be transmitted through a given fiber infrastructure but generally requires higher signal-to-noise ratios. The selection of modulation format represents a fundamental design trade-off in capacity planning between spectral efficiency (maximizing capacity per fiber) and reach (maximizing transmission distance for a given signal quality).

Modulation Format Trade-offs in Modern Coherent Systems

Contemporary coherent optical systems support adaptive modulation where the transmitter can dynamically select among multiple formats based on the measured GSNR. Common formats include:

QPSK (Quadrature Phase Shift Keying): 2 bits/symbol, low SNR requirement (~11 dB for BER = 10-3), maximum reach

8QAM (8-ary Quadrature Amplitude Modulation): 3 bits/symbol, medium SNR requirement (~15 dB), balanced reach/capacity

16QAM: 4 bits/symbol, medium-high SNR requirement (~18 dB), reduced reach, higher capacity

32QAM: 5 bits/symbol, high SNR requirement (~21 dB), short reach, very high capacity

64QAM: 6 bits/symbol, very high SNR requirement (~24 dB), metro applications only, maximum capacity

Dual polarization effectively doubles the spectral efficiency: DP-16QAM achieves 8 bits/s/Hz (4 bits/symbol × 2 polarizations) before accounting for forward error correction overhead.

Capacity planning requires selecting the optimal modulation format for each network segment based on the available GSNR, considering both the physical layer constraints and traffic demand requirements. A submarine cable system spanning 8,000 km might employ DP-16QAM (8 bits/s/Hz) for maximum capacity per fiber pair, accepting the higher GSNR requirement and deploying sufficient repeaters to maintain signal quality. A terrestrial long-haul system might use DP-8QAM (6 bits/s/Hz) to extend reach between regeneration sites. Metro networks with short distances and high GSNR can leverage DP-64QAM (12 bits/s/Hz) to maximize fiber capacity.

2. Advanced Optimization Algorithms for Capacity Planning

2.1 Multi-Commodity Flow Optimization

Network capacity planning fundamentally addresses a multi-commodity flow problem: how to route multiple traffic demands (commodities) across a shared network infrastructure to meet service level agreements while minimizing cost and maximizing resource utilization. The classical multi-commodity flow formulation provides a powerful framework for optimal network design, capacity allocation, and traffic engineering.

In the multi-commodity flow model, the network is represented as a directed graph G = (V, E) where V represents network nodes (routers, optical switches) and E represents links (fiber spans, wavelength channels). Each commodity k represents a traffic demand from source sk to destination tk with required bandwidth dk. The optimization objective is to find flow assignments for each commodity on each link that satisfy all demands while respecting link capacity constraints and minimizing an objective function such as total network cost, maximum link utilization, or total propagation delay.

Linear Programming Formulation for Multi-Commodity Flow

Decision Variables:

fk,e = flow of commodity k on edge e (continuous, ≥ 0)

Objective: Minimize total network cost

minimize: Σe∈E ce × Σk∈K fk,e

Subject to constraints:

1) Flow conservation at each node (except source/sink):

For each commodity k, each node v ≠ sk, tk:

Σe∈in(v) fk,e - Σe∈out(v) fk,e = 0

2) Flow generation at source:

Σe∈out(sk) fk,e - Σe∈in(sk) fk,e = dk

3) Flow termination at sink:

Σe∈in(tk) fk,e - Σe∈out(tk) fk,e = dk

4) Link capacity constraints:

Σk∈K fk,e ≤ Ce for all edges e

Where:

ce = cost per unit flow on edge e

dk = demand for commodity k (bandwidth requirement)

Ce = capacity of edge e

in(v) = set of edges entering node v

out(v) = set of edges leaving node v

Practical Example: Small network with 3 commodities

Network: 5 nodes, 7 bidirectional links

Commodities:

k1: A→E, demand = 100 Gb/s

k2: B→D, demand = 50 Gb/s

k3: C→E, demand = 75 Gb/s

Link capacities: 200 Gb/s each

Link costs: proportional to physical distance

Solution approach:

1) Formulate LP with 3 commodities × 14 directed edges = 42 variables

2) Add 5 × 3 = 15 flow conservation constraints

3) Add 14 capacity constraints

4) Solve using simplex or interior-point method

Result: Optimal routing minimizing weighted path lengths

Computation time: milliseconds for small networks

Challenge: scales to thousands of variables for real networks

The multi-commodity flow LP provides globally optimal solutions when continuous flow splitting is permitted and all costs are linear. However, practical network implementations face additional constraints. Optical networks must allocate integer numbers of wavelength channels. Traffic demands often cannot be arbitrarily split across multiple paths due to packet reordering concerns or wavelength contention. Equipment comes in discrete capacity increments (10G, 100G, 400G line cards) rather than continuous values. These realities require extending the basic LP formulation to integer programming and mixed-integer programming variants.

2.2 Routing and Wavelength Assignment (RWA) Problem

In wavelength-routed optical networks, capacity planning must solve the Routing and Wavelength Assignment problem: for each connection request, select a physical path through the network and assign a wavelength (or set of wavelengths for multi-carrier transponders) such that no two connections sharing a fiber link use the same wavelength. This wavelength continuity constraint fundamentally distinguishes optical network planning from traditional packet network routing.

The RWA problem is NP-complete, meaning no polynomial-time algorithm is known to find optimal solutions for large problem instances. Practical capacity planning tools employ a hierarchy of solution approaches. For offline planning with known traffic matrices, Integer Linear Programming formulations can find provably optimal or near-optimal solutions for networks with dozens of nodes and hundreds of wavelengths, albeit with computation times ranging from seconds to hours. For real-time provisioning or very large networks, heuristic algorithms provide good solutions in milliseconds.

Common RWA Heuristic Algorithms

First-Fit Wavelength Assignment: After computing a path using shortest-path routing, assign the lowest-indexed available wavelength. Simple, fast, but can lead to wavelength fragmentation.

Least-Used Wavelength Assignment: Select the wavelength currently used by the fewest connections. Balances wavelength utilization but requires global network state knowledge.

Most-Used Wavelength Assignment: Pack connections onto the smallest number of distinct wavelengths, leaving others completely free. Maximizes potential for future wavelength reclamation.

k-Shortest Paths with Sequential Assignment: Compute k candidate paths sorted by cost/length, attempt wavelength assignment on each path in sequence until success. Balances path quality with wavelength availability.

Tabu Search and Simulated Annealing: Metaheuristic approaches that explore the solution space through guided random walks, escaping local optima through controlled randomization. Can find high-quality solutions for very large problem instances.

Modern capacity planning tools often employ hybrid approaches: use ILP optimization for initial network design and periodic reoptimization (running overnight), combined with fast heuristics for incremental capacity additions and failure recovery scenarios requiring sub-second response times. Machine learning models trained on historical RWA solutions can also predict good wavelength assignments, achieving near-optimal blocking probability with minimal computation.

2.3 Multi-Layer Optimization: IP over Optical

Contemporary network capacity planning must address the interaction between multiple network layers. IP routers forward packets based on longest-prefix match routing tables. These routers connect via optical transport infrastructure that moves traffic as wavelength channels between router ports. Capacity planning decisions at one layer impact requirements at other layers, creating a complex multi-layer optimization problem.

Consider a simple scenario: an IP link between two routers is congested. The capacity planner has several options: upgrade the optical transponders to higher-rate interfaces (100G to 400G), provision additional parallel wavelengths between the same router pair, route some IP traffic via alternative paths through intermediate routers, or deploy additional optical transport bandwidth by installing new fiber cables. Each option has different cost, capacity, and latency implications. The optimal choice depends on forecasted traffic growth, equipment costs, operational complexity, and network resilience requirements.

The multi-layer optimization challenge intensifies in networks using coherent pluggable optics, where router line cards directly generate optical wavelengths without separate transponder equipment. Here, decisions about IP routing topology, wavelength assignments, and modulation format selection must be made jointly. A wavelength operating at lower modulation order (lower spectral efficiency) can reach longer distances, potentially enabling a direct optical connection between routers and avoiding IP-layer routing hops. Conversely, using higher modulation order reduces optical reach but increases capacity per wavelength, potentially requiring fewer wavelength channels to carry the same traffic volume.

3. AI and Machine Learning in Capacity Planning

3.1 Traffic Prediction Using Neural Networks

Accurate traffic forecasting is the foundation of effective capacity planning. Traditional statistical methods such as exponential smoothing, ARIMA models, and linear regression have served network operators for decades, providing reasonable predictions when traffic growth follows historical trends. However, modern networks exhibit complex, non-stationary traffic patterns influenced by content delivery network behaviors, video streaming quality adaptation algorithms, software update schedules, and coordinated bot activity. These phenomena create traffic patterns that violate the assumptions of classical time series models.

Deep learning approaches, particularly recurrent neural networks with Long Short-Term Memory units and more recent Transformer architectures, have demonstrated superior forecasting accuracy on network traffic time series. These models can automatically learn hierarchical representations of traffic patterns across multiple time scales: diurnal patterns with morning and evening peaks, weekly patterns with weekday versus weekend differences, seasonal variations driven by holidays and major events, and secular trends reflecting long-term growth. The models can also incorporate exogenous variables such as weather conditions, scheduled maintenance windows, and marketing campaign schedules.

A typical deep learning traffic prediction pipeline operates as follows. Historical traffic measurements at 5-minute or 15-minute granularity from network management systems feed into a preprocessing stage that normalizes data, handles missing values, and identifies outliers. The processed time series enters a multi-layer LSTM network that learns to predict traffic demand at various forecast horizons (1 hour ahead, 1 day ahead, 1 week ahead). The model trains on historical data using backpropagation through time, minimizing mean squared prediction error. During operation, the model continuously ingests new traffic measurements and generates updated forecasts, providing network planners with probabilistic predictions including confidence intervals.

Critical Considerations for ML-Based Traffic Prediction

While machine learning offers powerful forecasting capabilities, several challenges must be addressed in production deployments. Training data must span multiple years to capture seasonal patterns and exceptional events. Models require periodic retraining as network usage patterns evolve. Forecast confidence intervals must be calibrated to avoid systematic under or over-prediction. Most critically, models must be robust to unprecedented events like global pandemics or infrastructure failures that produce traffic patterns outside the training distribution. Hybrid approaches combining ML predictions with domain expert judgment often outperform purely algorithmic methods in practice.

3.2 Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Resource Allocation

While supervised learning excels at prediction tasks, reinforcement learning provides a framework for learning optimal decision policies through interaction with an environment. In network capacity planning, reinforcement learning can discover resource allocation strategies that maximize long-term objectives (network availability, cost efficiency) while responding to dynamic traffic conditions and failure scenarios.

The reinforcement learning formulation models the network as a Markov Decision Process. The state space encompasses current traffic loads, link utilizations, equipment failures, and available resources. Actions correspond to capacity planning decisions: provision additional wavelengths, upgrade transponder line cards, route traffic via alternate paths, or defer action. A reward function encodes the planning objectives, providing positive rewards for meeting service level agreements and negative rewards for equipment costs and service disruptions. The RL agent learns a policy mapping states to actions that maximizes expected cumulative future rewards.

Deep reinforcement learning algorithms such as Deep Q-Networks, Proximal Policy Optimization, and Actor-Critic methods can handle the high-dimensional state spaces and continuous action spaces encountered in realistic network planning problems. These algorithms have demonstrated success in optimizing data center network traffic engineering, wireless spectrum allocation, and optical network reconfiguration. A key advantage of RL approaches is their ability to learn from simulated experience using network digital twins, avoiding the risks and costs of experimenting with live production networks.

3.3 Graph Neural Networks for Network Topology Analysis

Network topology itself embodies critical structural information that influences capacity planning decisions. Graph Neural Networks provide a natural framework for learning representations of network graphs that capture both local connectivity patterns and global topological properties. GNNs can predict link failure probabilities based on topology position, identify bottleneck locations that constrain network capacity, and recommend strategic placements for capacity upgrades.

A GNN operates through iterative message passing: each node aggregates information from neighboring nodes, updates its representation, and passes messages to its neighbors. After several iterations, node representations capture information from increasingly distant neighbors, effectively learning a distributed representation of the global network structure. These learned representations can feed into downstream tasks such as link congestion prediction, node importance ranking, or capacity expansion recommendation.

Recent research has applied GNNs to routing optimization, showing that networks trained on moderate-sized network instances can generalize to larger topologies. This transfer learning capability is particularly valuable for capacity planning, where the ability to apply insights from simulated or small-scale networks to enterprise or carrier-scale deployments offers substantial efficiency gains compared to solving optimization problems from scratch for each network configuration.

4. Submarine Cable System Capacity Planning

4.1 Unique Constraints of Submarine Systems

Submarine cable systems present capacity planning challenges that differ fundamentally from terrestrial networks. A transoceanic cable may span 10,000 kilometers or more, operate for 25 years without physical access for upgrades, cost hundreds of millions to billions of dollars, and carry significant fractions of intercontinental internet traffic. These characteristics demand exceptionally thorough capacity planning during the initial design phase, as subsequent capacity expansion options are severely limited compared to terrestrial systems.

The power budget constraint dominates submarine system design. Unlike terrestrial networks with ubiquitous grid power, submarine cables rely on shore-based power feeding equipment that injects direct current through the cable's copper conductor to power optical amplifier repeaters deployed every 50-80 km on the seafloor. The maximum voltage that can be applied is typically limited to 15-20 kV by insulation technology and safety regulations. The current-carrying capacity of the conductor determines the available power. This fixed power envelope must be allocated among all fiber pairs and all optical amplifiers, creating a fundamental trade-off between fiber count (parallelism) and amplifier power per fiber (signal quality).

Capacity planning for submarine systems therefore involves optimizing the degree of parallelism. A cable with more fiber pairs can carry more total capacity through spatial division multiplexing, but each fiber receives less amplifier power, reducing the achievable GSNR and limiting modulation order or transmission reach. Conversely, a cable with fewer fiber pairs can allocate more power per fiber, achieving higher GSNR and enabling higher spectral efficiency or longer distances without regeneration, but offers less total capacity. The optimal design point depends on the specific traffic requirements, cable length, and economic factors.

Submarine Cable Power Budget Analysis

Total available power from shore feeding:

Ptotal = Vmax × Imax

Power consumed by N repeaters with F fiber pairs:

Pconsumed = N × F × Pamp + Poverhead

Power budget constraint:

Pconsumed ≤ Ptotal

Capacity scaling relationship (Shannon limit):

Ccable ∝ F × log2(1 + SNR)

Where SNR depends on power per fiber pair:

SNR ∝ Pamp / F

Practical Example: 10,000 km transatlantic cable

Given parameters:

Vmax = 15,000 V (shore power feed)

Imax = 1.0 A (conductor current limit)

Ptotal = 15,000 W = 15 kW

Repeater spacing = 50 km

N = 10,000/50 = 200 repeaters

Poverhead = 3,000 W (telemetry, monitoring)

Available for amplifiers: 15,000 - 3,000 = 12,000 W

Scenario A: 6 fiber pairs (high capacity per pair)

Pamp per FP = 12,000 / (200 × 6) = 10 W per amplifier

Higher power → higher GSNR → higher modulation order

Can support 64QAM modulation

Cper FP ≈ 30 Tb/s, Total = 180 Tb/s

Scenario B: 12 fiber pairs (moderate capacity per pair)

Pamp per FP = 12,000 / (200 × 12) = 5 W per amplifier

Lower power → lower GSNR → lower modulation order

Limited to 16QAM modulation

Cper FP ≈ 20 Tb/s, Total = 240 Tb/s

Scenario C: 24 fiber pairs (lower capacity per pair)

Pamp per FP = 12,000 / (200 × 24) = 2.5 W per amplifier

Minimal power → minimal GSNR → minimal modulation

Limited to QPSK modulation

Cper FP ≈ 12 Tb/s, Total = 288 Tb/s

Optimal choice depends on: traffic forecast, cost per FP,

terminal equipment capabilities, and upgrade strategy

4.2 Open Cable Architecture and GSNR Specification

The emergence of open cable architectures has transformed submarine capacity planning by decoupling wet plant (submarine cable, repeaters, branching units) from dry plant (terminal equipment, transponders, routers). In this model, the cable supplier designs and deploys the submarine infrastructure to meet a specified GSNR performance target, typically expressed as minimum GSNR in a reference bandwidth at the optical connection interface. Terminal equipment suppliers then independently develop transponders and modems optimized to extract maximum capacity from the available GSNR.

This separation enables technology evolution. The submarine cable, designed for 25-year service life, provides stable GSNR performance throughout its lifetime. Terminal equipment, with 5-7 year technology cycles, can be upgraded multiple times over the cable's life to incorporate advances in digital signal processing, forward error correction, and constellation shaping. A cable deployed in 2015 supporting 100G per wavelength with QPSK modulation might be upgraded in 2020 to 200G with 16QAM, and again in 2025 to 400G with probabilistically-shaped 64QAM, all using the same submarine infrastructure.

Capacity planning in the open cable model requires careful GSNR specification. The cable supplier must guarantee minimum GSNR across all wavelength channels in the usable spectrum (typically C-band, possibly extended to C+L band), accounting for worst-case channel positions, aging effects, and environmental variations. Terminal equipment suppliers design to this guaranteed GSNR, incorporating appropriate margin for component tolerances and implementation penalties. Network operators forecast capacity needs and select terminal equipment configurations that match or exceed requirements while staying within cable GSNR budget.

Open Cable GSNR Guidelines (ITU-T and SubOptic)

Industry standards organizations have developed guidelines for open cable GSNR specifications to enable multi-vendor interoperability. Typical requirements include:

Reference Bandwidth: GSNR measured in 12.5 GHz bandwidth (accommodating modern transponder symbol rates up to ~100 GBaud)

Minimum GSNR: 10-15 dB depending on cable length and design (longer cables have lower GSNR)

GSNR Variation: Maximum 2-3 dB variation across wavelength channels to ensure uniform performance

Spectral Coverage: Full C-band (1530-1565 nm, 96+ channels at 50 GHz spacing) guaranteed, L-band (1565-1625 nm) optional

Aging Budget: 1-2 dB margin allocated for component degradation over 25-year cable life

These specifications enable terminal equipment vendors to guarantee performance independent of specific cable implementation details, facilitating competition and innovation in transponder technology.

4.3 Spatial Division Multiplexing: Multi-Core Fiber Cables

As submarine cable capacity requirements approach and exceed 1 Petabit per second, the industry is exploring spatial division multiplexing using multi-core fiber technology. A multi-core fiber contains multiple independent fiber cores within a single fiber cladding, effectively multiplying capacity without proportionally increasing cable size, weight, or deployment cost. Early deployments use 4-core or 6-core fibers, with research demonstrations extending to 12-core and beyond.

Multi-core fiber introduces new capacity planning considerations. The amplification technology must efficiently amplify all cores simultaneously while maintaining low noise figure and acceptable power consumption. Multi-core EDFAs with shared pump lasers offer better power efficiency than N independent single-core amplifiers, but at the cost of increased complexity and potentially reduced redundancy. Core-to-core crosstalk, though minimized through careful fiber design, must be accounted for in GSNR budgets. The terminal equipment must interface with all cores, requiring multi-core fan-out components and parallel transponder arrays.

Capacity planning with multi-core fibers focuses on maximizing aggregate cable capacity subject to power and cost constraints. The optimization involves fiber core count, core-to-core spacing (affects crosstalk), amplifier design (individual core pumping versus shared pumping), and per-core channel count. Current generation submarine cables using 4-6 core fibers achieve 400-600 Tb/s on transatlantic distances, with projections for multi-Petabit cables using 12-24 core fibers by 2030.

5. Industrial Implementation and Best Practices

5.1 Hierarchical Planning Approach

Industrial-strength capacity planning tools employ a hierarchical decision-making structure that mirrors the time scales and scope of different planning activities. Strategic planning operates on 3-5 year horizons, determining major infrastructure investments such as new submarine cable deployments, metro network fiber builds, or data center interconnect projects. Tactical planning works at 6-12 month timescales, deciding equipment procurement, network expansions within existing infrastructure, and configuration changes. Operational planning happens daily or weekly, handling traffic engineering, failure recovery, and incremental capacity additions.

Each planning level uses optimization techniques appropriate to its time scale and decision complexity. Strategic planning employs sophisticated mathematical programming models, often running overnight or over weekends to explore large solution spaces and evaluate multiple scenarios. These models might optimize fiber route selection, equipment vendor choices, and technology selection (single-core versus multi-core fiber, DWDM versus packet-optical integration) considering forecasted demand, cost models, and risk factors.

Tactical planning balances optimization quality with computational speed. Tools must evaluate capacity upgrade options within hours to support procurement decision timelines. Common approaches include decomposition methods that break large optimization problems into smaller subproblems (per-metro-region or per-traffic-class optimizations that can run in parallel), heuristic algorithms that sacrifice optimality for computational tractability, and hybrid methods combining limited-scope exact optimization with broader heuristic search.

Operational planning requires real-time or near-real-time decision making. When a fiber cut occurs, traffic must be rerouted within seconds to minutes to minimize service impact. When a major content provider requests emergency capacity for a product launch, provisioning decisions must happen within hours. These timescales preclude complex optimization; instead, operational tools rely on pre-computed provisioning plans, rule-based decision systems, and fast heuristics. Machine learning models trained on historical planning decisions can predict good configurations instantly, enabling automated responses to common scenarios while escalating unusual situations to human planners.

5.2 Scenario Planning and Sensitivity Analysis

Network capacity planning must account for substantial uncertainty in future demand, technology evolution, and economic conditions. A submarine cable commissioned in 2025 must provide value through 2050, spanning multiple generations of terminal equipment technology and dramatic changes in traffic patterns. Terrestrial networks face similar uncertainties over shorter horizons: cloud migration trends, 5G deployment rates, and enterprise work-from-home policies all influence capacity requirements in ways difficult to predict accurately years in advance.

Robust planning methodologies address uncertainty through scenario analysis. Rather than optimizing for a single demand forecast, planners develop multiple scenarios representing different possible futures: high growth, moderate growth, low growth, with variations in technology adoption rates, geographic distribution, and service mix. The capacity plan aims to perform acceptably across all scenarios, trading some optimality in any single scenario for robustness to forecast uncertainty.

Sensitivity analysis quantifies how plan performance degrades as assumptions change. Key metrics include: What traffic growth rate makes the planned capacity insufficient? How much does total cost increase if fiber installation costs rise 20%? What is the impact of a two-year delay in coherent transponder technology improvements? By answering these questions systematically, planners identify critical assumptions where small changes have large consequences, guiding risk mitigation efforts toward the most impactful areas.

Real Options Analysis in Network Planning

Financial techniques from real options analysis increasingly inform network capacity planning decisions. The ability to defer an investment decision (wait for better demand visibility), expand capacity incrementally (start small, scale as needed), or abandon an under-performing asset (redeploy equipment to higher-value locations) has real economic value. Traditional net present value calculations ignore these flexibilities, potentially undervaluing modular, scalable network architectures relative to large upfront deployments. Modern planning frameworks use decision tree analysis, Monte Carlo simulation, and stochastic optimization to quantify option values and identify architectures that maximize strategic flexibility.

5.3 Integration with Business Processes

Effective capacity planning requires tight integration with broader business processes. Demand forecasting must incorporate input from sales teams tracking customer requirements, marketing teams planning new service launches, and strategic planning teams evaluating market opportunities. Equipment procurement must align capacity plans with vendor lead times, volume pricing tiers, and maintenance contract structures. Network operations must execute capacity additions while maintaining service levels, often requiring careful scheduling around maintenance windows and high-traffic periods.

Modern planning platforms integrate with IT systems across the organization. Network management systems provide real-time and historical performance data that feeds planning models. Order management systems trigger capacity planning evaluations when large customer contracts are signed. Financial systems provide cost and budget constraints. GIS systems supply geographic data for route planning. This integration enables automated workflows: when traffic growth on a link exceeds a threshold, the system automatically generates capacity upgrade proposals, estimates costs, checks budget availability, and routes requests to appropriate approvers.

The human element remains critical despite increasing automation. Expert network engineers bring domain knowledge that complements algorithmic optimization: understanding of vendor product roadmaps, awareness of regulatory constraints, insight into customer relationship dynamics, and intuition about emerging technology opportunities. The most effective planning organizations combine sophisticated tools with skilled practitioners, using automation to handle routine analysis while freeing engineers to focus on strategic questions, edge cases, and innovation.

5.4 Continuous Improvement and Learning

Network capacity planning is an iterative process that improves through learning from past decisions. Post-deployment reviews compare actual traffic growth and network performance against planning assumptions, identifying systematic biases in forecasting models or optimization heuristics. A/B testing of planning strategies, where different approaches are applied to similar network segments, provides empirical evidence for best practices. Regular calibration of planning parameters (cost models, traffic growth rates, technology evolution curves) using operational data keeps models aligned with reality.

Organizations that excel at capacity planning establish formal knowledge management processes. Planning decisions are documented with rationale, key assumptions, and expected outcomes. Results are tracked and analyzed. Lessons learned are captured in planning guidelines and tool configurations. This institutional knowledge accumulates over time, enabling new engineers to quickly reach competence and the organization to avoid repeating past mistakes. Machine learning systems can partially automate this knowledge capture, learning planning heuristics from historical decisions and continuously refining their recommendations based on observed outcomes.

Conclusion

Network capacity planning represents one of the most challenging and consequential problems in telecommunications engineering. The mathematical foundations—rooted in Shannon's information theory, graph theory, and stochastic processes—provide elegant frameworks for understanding fundamental limits and optimality conditions. Yet practical planning must navigate a vast space of design choices, balance competing objectives, accommodate uncertain futures, and operate within real-world constraints that defy simple optimization formulations.

The field continues to evolve rapidly. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are transforming how networks predict demand, optimize resource allocation, and respond to changing conditions. Coherent optical technology advances enable unprecedented spectral efficiency and flexible network architectures. Software-defined networking and network function virtualization blur traditional boundaries between network layers. Submarine cable systems push toward Petabit-scale capacities through spatial division multiplexing and advanced modulation formats. Each of these developments creates new opportunities and challenges for capacity planners.

Success in capacity planning requires mastery of diverse disciplines: applied mathematics for optimization algorithms, signal processing and optical physics for understanding transmission systems, computer science for algorithmic implementation and data processing, economics for cost modeling and investment analysis, and systems thinking for managing complexity and interdependencies. The senior engineers and network architects who excel in this field combine deep technical knowledge with practical judgment, analytical rigor with creative problem-solving, and attention to detail with strategic vision.

As networks continue their relentless growth in capacity, complexity, and criticality to global infrastructure, the importance of sophisticated capacity planning will only increase. The techniques, models, and frameworks presented in this deep dive represent the current state of the art, but also just one point in an ongoing evolution. Future advances in quantum communications, free-space optical links, neuromorphic computing, and technologies yet to be conceived will create new capacity planning challenges and opportunities. The fundamental principles—maximizing information transfer subject to physical constraints, allocating scarce resources efficiently, planning under uncertainty—will endure while their specific realizations continue to advance.

For engineers aspiring to excellence in network capacity planning, the path forward involves continuous learning across multiple domains, hands-on experience with real systems and planning tools, engagement with research literature to stay current with emerging techniques, and cultivation of both analytical skills and practical wisdom. The field offers intellectually rich problems with tangible real-world impact, combining the elegance of mathematical optimization with the complexity of large-scale engineered systems. Those who invest the effort to develop deep expertise will find rewarding careers at the cutting edge of global telecommunications infrastructure.

References and Further Reading

Fundamental Theory

[1] C. E. Shannon, "A Mathematical Theory of Communication," Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, pp. 379-423, 1948.

[2] A. Carena, V. Curri, G. Bosco, P. Poggiolini, and F. Forghieri, "Modeling of the Impact of Nonlinear Propagation Effects in Uncompensated Optical Coherent Transmission Links," Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 30, no. 10, pp. 1524-1539, 2012.

Submarine Cable Systems

[3] J.-X. Cai, G. Mohs, and N. S. Bergano, "Ultra-Long-Distance Undersea Transmission Systems," in Optical Fiber Telecommunications VII, Academic Press, 2019.

[4] E. R. Hartling, A. Pilipetskii, D. Evans, E. Mateo, et al., "Design, Acceptance and Capacity of Subsea Open Cables," Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 742-756, 2021.

Optimization and Algorithms

[5] R. K. Ahuja, T. L. Magnanti, and J. B. Orlin, Network Flows: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications, Prentice Hall, 1993.

[6] M. Pióro and D. Medhi, Routing, Flow, and Capacity Design in Communication and Computer Networks, Morgan Kaufmann, 2004.

Machine Learning Applications

[7] K. Benziane, M. Rastegarfar, and C. S. Cavdar, "Forecasting in Optical Networks Using Deep Learning," Journal of Optical Communications and Networking, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. E102-E112, 2021.

[8] L. Xiao, Z. Xu, and A. Xu, "Graph Neural Networks for Routing Optimization in Optical Networks," IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 60, no. 5, pp. 92-98, 2022.

Industry Standards and Guidelines

[9] ITU-T Recommendation G.709, "Interfaces for the Optical Transport Network," 2020.

[10] SubOptic Open Cables Working Group, "Open Cable Specification Guidelines," 2022.

Advanced Topics

[11] G. Rademacher, R. S. Luis, B. J. Puttnam, et al., "Long-Haul Transmission Over Multi-Core Fibers," Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1590-1596, 2022.

[12] Y. Yamamoto, T. Kawasaki, and K. Nakamura, "AI-Driven Network Planning and Optimization for 5G and Beyond," IEEE Network, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 45-52, 2024.

Recommended Book

Sanjay Yadav, Optical Network Communications: An Engineer's Perspective – Bridge the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Optical Networking.

Developed by MapYourTech Team

For educational purposes in Optical Networking Communications Technologies

Note: This guide is based on industry standards, best practices, and real-world implementation experiences. Specific implementations may vary based on equipment vendors, network topology, and regulatory requirements. Always consult with qualified network engineers and follow vendor documentation for actual deployments.

Feedback Welcome: If you have any suggestions, corrections, or improvements to propose, please feel free to write to us at feedback@mapyourtech.com

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here