HomePosts tagged “Telecommunications”

Telecommunications

Showing 1 - 7 of 7 results

In this comprehensive exploration of 400G ZR and ZR+ optical communication standards, we delve into the advanced world of Probabilistic...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

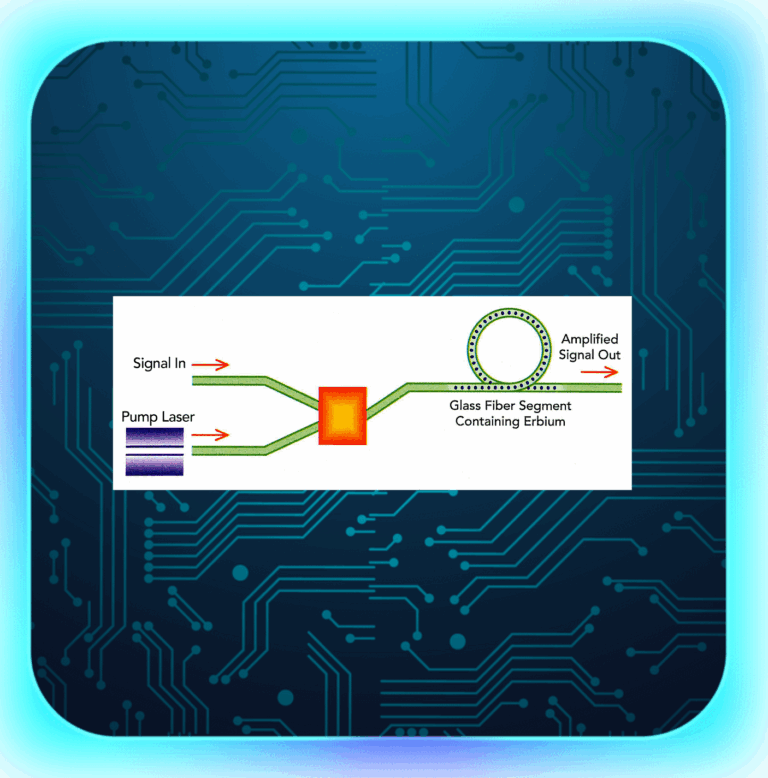

Optical Amplifiers (OAs) are key parts of today’s communication world. They help send data under the sea, land and even...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

Optical networks are the backbone of the internet, carrying vast amounts of data over great distances at the speed of...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

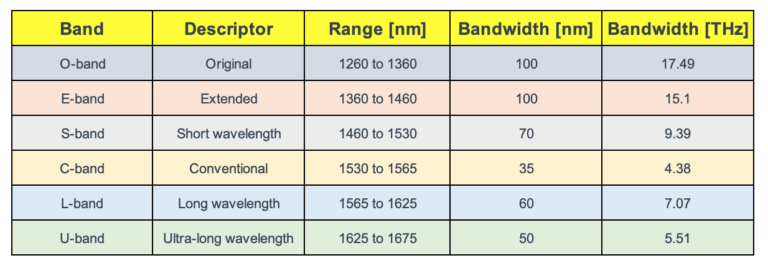

When we talk about the internet and data, what often comes to mind are the speeds and how quickly we...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

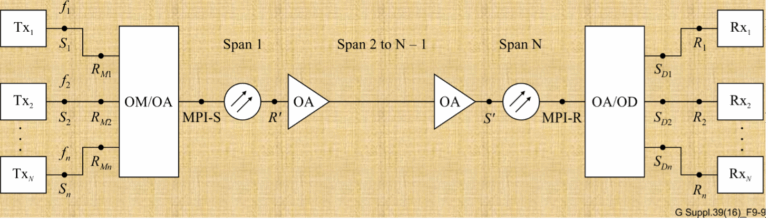

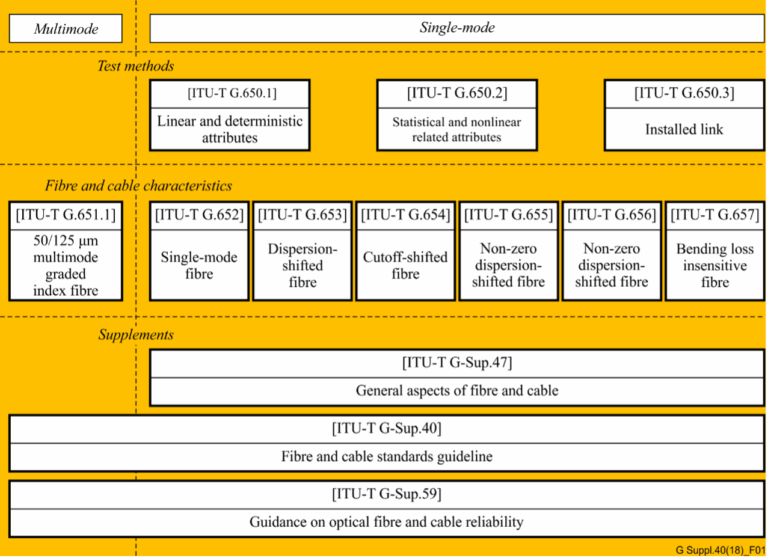

In the realm of telecommunications, the precision and reliability of optical fibers and cables are paramount. The International Telecommunication Union...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

Carrier Ethernet: A Formal Definition The MEF (Metro Ethernet Forum) has defined Carrier Ethernet as the “ubiquitous, standardized, Carrier-class service defined by five...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

Explore Articles

Filter Articles

ResetExplore Courses

Tags

automation

ber

Chromatic Dispersion

coherent optical transmission

Data transmission

DWDM

edfa

EDFAs

Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers

fec

Fiber optics

Fiber optic technology

Forward Error Correction

Latency

modulation

network automation

network management

Network performance

noise figure

optical

optical amplifiers

optical automation

Optical communication

Optical fiber

Optical network

optical network automation

optical networking

Optical networks

Optical performance

Optical signal-to-noise ratio

Optical transport network

OSNR

OTN

Q-factor

Raman Amplifier

SDH

Signal integrity

Signal quality

Slider

submarine

submarine cable systems

submarine communication

submarine optical networking

Telecommunications

Ticker