6 min read

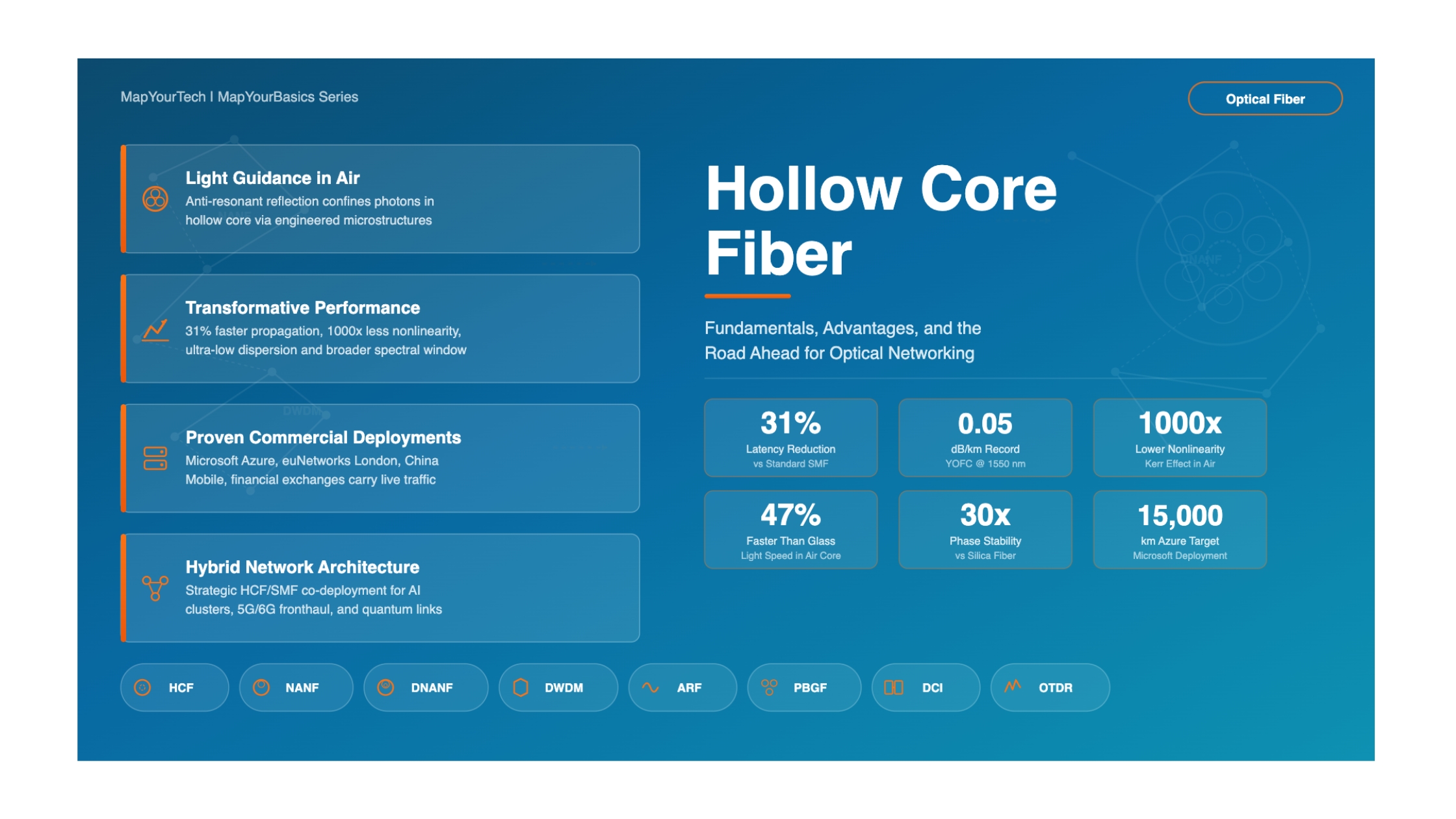

Hollow Core Fiber: Fundamentals, Advantages, and the Road Ahead

A comprehensive guide to Hollow Core Fiber (HCF) technology -- from basic principles and fiber types to real-world deployments, current challenges, and the technology's trajectory toward mainstream optical networking.

1. Introduction

For over four decades, optical fiber communication has relied on a single foundational principle: guiding light through a solid glass core using total internal reflection. Standard Single-Mode Fiber (SMF) built on this principle has become the backbone of global telecommunications, with billions of kilometers deployed worldwide. Yet solid-core silica fiber has inherent physical limitations -- its refractive index slows light to roughly 69% of its vacuum speed, its glass medium introduces nonlinear effects at high optical power, and Rayleigh scattering imposes a fundamental floor on attenuation near 0.14 dB/km at 1550 nm.

Hollow Core Fiber (HCF) represents a fundamentally different approach: instead of sending light through glass, it guides photons through an air-filled (or vacuum) core, using engineered microstructures in the cladding to confine light. This seemingly simple change -- replacing glass with air as the transmission medium -- unlocks a cascade of performance advantages that address the core limitations of conventional fiber. Light travels approximately 47% faster through air than through silica glass, nonlinear optical effects are reduced by roughly 1,000 times, and recent HCF designs have achieved attenuation below the Rayleigh scattering limit of solid silica.

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of HCF technology, covering its guiding principles, fiber types, performance advantages, practical challenges, commercial maturity, and best-suited use cases. It is designed to serve as a reference-grade resource for optical networking professionals, engineers, and researchers seeking to understand where HCF stands as of 2025 and where it is headed.

2. Fundamental Principles of Hollow Core Fiber

2.1 How Light is Guided in Air

In a conventional SMF, light is confined to a solid silica core (approximately 8-10 µm diameter) by a surrounding cladding with a slightly lower refractive index. The mechanism is Total Internal Reflection (TIR), which occurs because the core's refractive index (~1.468) is higher than the cladding's (~1.462).

HCF inverts this relationship. The core is hollow -- filled with air or vacuum -- and has a lower refractive index (~1.0) than the surrounding glass cladding (~1.45). TIR cannot occur in this geometry because light would refract outward at the core-cladding interface. Instead, HCF relies on engineered microstructures in the cladding to prevent light from escaping. The two primary confinement mechanisms that have emerged are the Photonic Bandgap (PBG) effect and Anti-Resonant (AR) reflection.

HCF guides light through air by surrounding the hollow core with carefully designed glass microstructures that act as "mirrors," preventing photons from leaking into the cladding. Because more than 99.9% of the optical power travels in air rather than glass, HCF inherits the superior optical properties of air: faster propagation, negligible nonlinearity, and reduced scattering.

Figure 1: Cross-section comparison of Standard SMF (left) with solid silica core and Total Internal Reflection, versus Hollow Core NANF (right) with air core and nested anti-resonant capillaries.

2.2 Types of Hollow Core Fiber

Two principal families of HCF have been developed, each distinguished by how the cladding structure confines light to the hollow core.

2.2.1 Photonic Bandgap Fibers (PBGFs)

PBGFs use a periodic microstructure in the cladding -- essentially a two-dimensional photonic crystal made of a regular array of air holes in silica. This periodic arrangement creates a photonic bandgap: a range of wavelengths (and propagation angles) that are forbidden from propagating radially outward. Light at wavelengths within the bandgap is effectively reflected back into the hollow core "defect" at the center of the structure.

PBGFs were the first type of HCF to be seriously explored for telecommunications. The lowest loss achieved in a PBGF was 1.7 dB/km at 1565 nm (reported by Mangan et al. in 2004), a record that stood for many years. However, PBGFs have inherent drawbacks. Their operational bandwidth is relatively narrow, limited by the width of the bandgap itself. They also tend to support multiple transverse modes in the relatively large core (~25 µm diameter), requiring careful mode management. Additionally, surface modes -- modes that exist at the interface between the hollow core and the periodic cladding -- create narrow spectral regions of high loss, which reduce the usable transmission window.

2.2.2 Anti-Resonant Fibers (ARFs)

ARFs employ a different confinement principle. Instead of a periodic crystal lattice, the cladding consists of one or more rings of thin-walled glass capillaries (tubes) surrounding the hollow core. Light confinement depends on the anti-resonant reflection of light from these thin glass membranes. At wavelengths where the membrane thickness corresponds to a resonance condition, light leaks through the walls. At anti-resonant wavelengths -- where the glass walls act as effective reflectors -- light is strongly confined in the core.

The ARF family has seen extraordinary progress in recent years and now dominates state-of-the-art HCF research. ARFs offer broader transmission bandwidths than PBGFs (potentially spanning octaves of spectral range) and are generally less sensitive to fabrication imperfections. Two revolutionary refinements within the ARF family have driven this progress:

Nested Anti-resonant Nodeless Fiber (NANF): Proposed by Francesco Poletti at the University of Southampton in 2014, the NANF architecture introduced two critical innovations. First, the cladding capillaries are "nodeless" -- they do not touch each other. In earlier designs, the points of contact between capillaries (nodes) created structural imperfections that acted as leakage pathways. Eliminating nodes produces a smoother, wider, low-loss transmission window. Second, smaller capillaries are "nested" inside the primary capillaries, adding additional anti-resonant reflecting surfaces that further suppress light leakage from the core.

Double-Nested Anti-resonant Nodeless Fiber (DNANF): A further refinement where a second layer of nesting is added, creating even more reflecting surfaces. The DNANF design is responsible for multiple record-low loss achievements and represents the current state of the art in HCF performance.

Figure 2: Evolution of HCF cladding designs from Photonic Bandgap (periodic lattice) through Tubular Anti-Resonant to state-of-the-art Nested (NANF) and Double-Nested (DNANF) architectures, with associated loss records.

| Parameter | Photonic Bandgap (PBGF) | Anti-Resonant (ARF/NANF/DNANF) |

|---|---|---|

| Guiding Mechanism | Photonic bandgap effect from periodic cladding | Anti-resonant reflection from thin glass membranes |

| Bandwidth | Narrow (tens of nm), limited by bandgap width | Very broad (potentially octave-spanning) |

| Best Reported Loss | 1.7 dB/km @ 1565 nm (2004) | <0.11 dB/km @ 1550 nm (OFC 2024, DNANF) |

| Mode Behavior | Relatively large core supports multiple modes | Effective single-mode operation achievable |

| Surface Modes | Problematic -- cause narrow high-loss features | Largely eliminated in nodeless designs |

| Fabrication Sensitivity | High sensitivity to structural imperfections | More tolerant; simpler non-periodic structures |

| Current Status | Commercially available (OFS AccuCore), niche use | State of the art; driving all new deployments |

3. Advantages of Hollow Core Fiber

The decision to guide light through air rather than glass produces a set of advantages that are not incremental improvements over SMF -- they are transformative, addressing fundamental physical limitations that have constrained optical networking for decades.

3.1 Ultra-Low Latency

This is the most immediately impactful advantage. Light travels at speed c in vacuum/air but is slowed to c/n in a material with refractive index n. In silica glass (group index ng ~ 1.467), the signal propagation speed is approximately 204,190 km/s. In the air core of HCF (neff ~ 1.0), the speed approaches 299,792 km/s -- the speed of light in vacuum.

-- Latency per kilometer comparison --

SMF latency = ng / c = 1.467 / (3 × 108 m/s) = 4.89 µs/km

HCF latency = neff / c = ~1.003 / (3 × 108 m/s) = ~3.34 µs/km

Latency saving = 4.89 - 3.34 = ~1.54 µs/km (round trip: ~3.08 µs/km)

-- This represents approximately a 31% reduction in propagation delay --

-- HCF effectively makes light 47% faster than in glass --This 1.54 µs/km one-way saving may seem small in absolute terms, but over meaningful distances it becomes significant. On a 100 km link, HCF saves approximately 154 µs one-way (308 µs round-trip). In high-frequency trading, where algorithmic strategies compete at nanosecond timescales, this advantage translates directly to revenue. In distributed AI training, where thousands of GPUs synchronize gradients across data center campuses, reduced latency improves parallel computing efficiency.

Figure 3: One-way propagation latency comparison between SMF and HCF over distance. The green shaded area represents the cumulative latency advantage of HCF, reaching 154 µs at 100 km.

3.2 Negligible Nonlinear Effects

Optical nonlinear effects -- including Self-Phase Modulation (SPM), Cross-Phase Modulation (XPM), Four-Wave Mixing (FWM), and Stimulated Brillouin Scattering (SBS) -- arise from the interaction between intense light and the silica medium. In conventional fiber, these effects impose strict limits on launch power, channel spacing, and achievable transmission distances.

In HCF, light propagates almost entirely in air, where the nonlinear coefficient is approximately 1,000 times lower than in silica. This means HCF can handle much higher optical power levels without degradation, support denser wavelength multiplexing without inter-channel interference, and enable longer unrepeated spans. The practical consequence is that system designers gain significantly more freedom in optical link engineering.

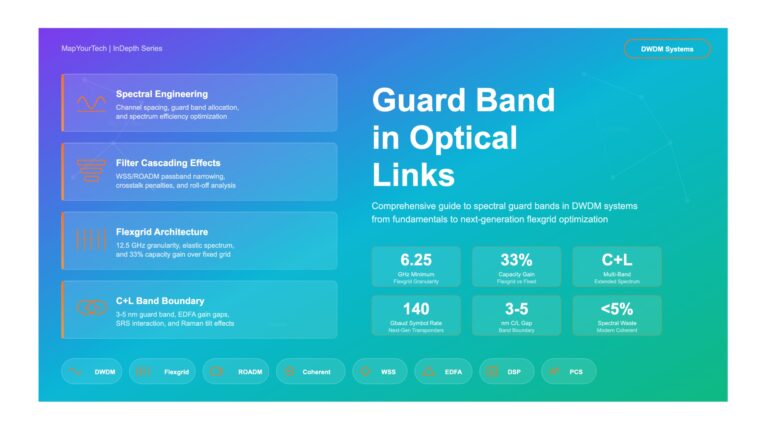

3.3 Broad Usable Bandwidth: Multi-Band Transmission

One of HCF's most transformative advantages is its ability to transmit light across a dramatically wider spectral range than conventional silica fiber. To understand why, it helps to first consider what limits SMF -- and then see how HCF breaks through those limits entirely.

3.3.1 Why Standard SMF is Band-Limited

In standard single-mode fiber, light propagates through a solid silica glass core. The usable transmission spectrum is fundamentally constrained by the material properties of that glass. Rayleigh scattering (caused by microscopic density variations in the glass) sets a minimum loss floor that increases at shorter wavelengths following an inverse fourth-power law. Infrared absorption from Si-O molecular vibrations rises sharply at wavelengths beyond ~1600 nm. And the historically troublesome hydroxyl (OH−) absorption peak at 1383 nm creates a high-loss barrier in the E-band, though modern G.652.D "zero water peak" fibers have largely suppressed this.

These combined silica material effects define the traditional telecom transmission bands within a roughly 1260-1675 nm window, with the lowest loss concentrated in the C-band (~0.17-0.18 dB/km at 1550 nm). The standard ITU-T defined bands for single-mode fiber are:

| Band | Wavelength Range | SMF Limitation | HCF Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-Band (Original) | 1260 – 1360 nm | Higher loss (~0.33-0.35 dB/km); low dispersion causes FWM susceptibility | Continuous low-loss transmission; no FWM penalty due to negligible nonlinearity |

| E-Band (Extended) | 1360 – 1460 nm | Water peak (OH−) at 1383 nm in legacy fiber; even G.652.D has ~0.35 dB/km | No water peak — air core contains no hydroxyl ions; seamless low-loss band |

| S-Band (Short) | 1460 – 1530 nm | ~0.25 dB/km; limited amplifier options (TDFA/BDFA still maturing) | Continuous low-loss spectrum; no glass absorption effects |

| C-Band (Conventional) | 1530 – 1565 nm | Lowest SMF loss (~0.17-0.18 dB/km); mature EDFA amplification | Comparable or lower loss in advanced DNANF; primary telecom deployment band for HCF |

| L-Band (Long) | 1565 – 1625 nm | Slightly higher loss (~0.20 dB/km); EDFA gain efficiency lower than C-band | Continuous low-loss coverage extending seamlessly from C-band |

| U-Band (Ultra-long) | 1625 – 1675 nm | Rising infrared absorption; no rare-earth amplifiers; silica approaches material limits | Air core avoids infrared absorption entirely; extended usable spectrum |

3.3.2 Why HCF Supports a Wider Spectrum

In hollow core fiber, light travels predominantly through air (or vacuum/inert gas), not through glass. This single fact eliminates the three material-dependent loss mechanisms that constrain silica fiber.

No Rayleigh Scattering Floor: The dominant loss mechanism in SMF -- Rayleigh scattering from the silica glass -- is eliminated because the light-glass overlap is minimal. In a well-designed NANF or DNANF, less than 0.1% of the optical power propagates in the glass walls. The fundamental loss floor in HCF is therefore not determined by the glass material but by the structural design quality of the fiber itself (confinement loss, surface scattering at the glass-air interface). This is why recent DNANF designs have achieved loss values below the Rayleigh scattering limit of silica -- something physically impossible in any solid-core fiber.

No Hydroxyl Absorption: The 1383 nm water peak that historically rendered the E-band unusable in silica fiber simply does not exist as a fundamental issue in HCF. Since light propagates through air, there are no OH− ions in the transmission medium. This means HCF naturally provides a continuous, uninterrupted low-loss window from the O-band through the L-band and beyond, without the spectral gaps that define silica fiber's transmission landscape.

No Infrared Material Absorption: The rising infrared absorption above ~1600 nm in silica (caused by Si-O bond vibrations) does not affect HCF. The air core is transparent well into the mid-infrared and beyond, limited only by the design of the cladding structure rather than fundamental material properties.

The anti-resonant guidance mechanism is inherently broadband. By engineering the cladding capillary wall thickness, a single AR-HCF can be designed to support an ultra-wide transmission window exceeding 1000 nm of contiguous bandwidth. This stands in contrast to SMF's roughly 400 nm usable window (O through U band), and even that 400 nm window has variable performance across bands.

Bandwidth Comparison: Advanced DNANF designs have demonstrated measured low-loss transmission from approximately 600 nm to beyond 2000 nm wavelength range. In the telecom region specifically, a single HCF can provide ~400 nm or more of contiguous low-loss bandwidth (compared to SMF's ~100 nm of C+L band optimized bandwidth). This represents a roughly 4x increase in the usable spectral window for a single fiber type.

3.3.3 Beyond Telecom: Spectral Windows Unique to HCF

HCF's ability to guide light in air extends its utility far beyond the conventional telecom bands. By adjusting the fiber's structural dimensions -- primarily the capillary wall thickness and core diameter -- designers can tailor HCF for optimized performance in spectral regions where solid silica fiber cannot compete.

The 850 nm Window: This wavelength is widely used for short-reach multimode fiber links within data centers and sensing applications. Researchers have demonstrated HCFs that outperform solid glass fibers at this wavelength, with a 10.9 km fiber achieving only 0.33 dB/km attenuation at 850 nm. This opens the door for single-mode, high-bandwidth operation in a spectral region historically constrained to multimode fiber.

The 1060 nm Window: This band is critical for high-power ytterbium-doped industrial fiber lasers. While commercial HCF products here show moderate attenuation (<100 dB/km), the primary advantage is an extraordinarily high damage threshold. Experiments have demonstrated delivery of 1 kilowatt (kW) of continuous-wave laser power over a 1 km length of HCF with a loss of just 0.74 dB/km -- a feat unattainable with solid-core fiber over such distances.

The 2 µm Window: HCFs perform well in the mid-infrared, with demonstrated losses in the 0.85-1.25 dB/km range around 2 µm. This spectral region is growing in importance for medical applications, remote sensing, and gas spectroscopy, and is a range where silica's intrinsic absorption increases significantly.

Visible Spectrum (400-700 nm): HCFs have been engineered for guidance in visible light, achieving losses comparable to or lower than solid-core equivalents at wavelengths like 660 nm. Advanced AR-HCF designs for the visible spectrum report theoretical confinement losses below 10−5 dB/m with excellent bending resistance at small radii, important for applications in endoscopy, bio-imaging, and UV laser delivery. A UV-guiding HCF has demonstrated single-mode transmission with only 0.13 dB/m loss at 320 nm wavelength, with no fiber degradation under sustained UV exposure.

Mid-Infrared (3-10 µm): HCFs, especially when using chalcogenide glass cladding instead of silica, can extend into the far infrared for molecular spectroscopy, environmental monitoring, and industrial process control applications -- regions entirely beyond the reach of silica-based fiber.

3.4 Ultra-Low Chromatic Dispersion

Chromatic Dispersion (CD) in HCF is dramatically lower than in SMF -- typically less than 2-3 ps/nm·km compared to approximately 17 ps/nm·km for standard SMF at 1550 nm. Lower dispersion means less signal broadening over distance, potentially allowing simpler and lower-power electronic compensation in Digital Signal Processors (DSPs). Microsoft has reported that reduced dispersion in HCF can lower power consumption for coherent transmission systems.

3.5 Enhanced Physical Security

HCF is inherently more difficult to tap than conventional fiber. The hollow core and sensitive microstructure mean that any physical intrusion -- drilling, tight bending, or evanescent coupling -- causes significant and detectable changes in signal loss, backscatter, or mode behavior. This makes real-time intrusion detection feasible through continuous monitoring, a property valued by government, defense, and financial sector networks requiring high physical-layer security.

3.6 Superior Phase Stability

Because the optical mode in HCF has minimal overlap with glass, its sensitivity to environmental perturbations (temperature, vibration, acoustic noise) is significantly reduced. HCF demonstrates 20-30 times better phase stability than SMF. This property is critical for fiber optic gyroscopes, quantum key distribution (QKD), and precision time-frequency transfer applications.

Figure 4: Comparative visualization of key performance parameters between HCF and standard SMF. HCF demonstrates advantages across latency, dispersion, nonlinearity, bandwidth, and phase stability.

- ~31% lower latency (1.54 µs/km saving)

- ~1,000x lower nonlinear coefficient

- Broader usable transmission bandwidth

- Ultra-low chromatic dispersion (<3 ps/nm·km)

- Enhanced physical security and tamper detection

- 20-30x better phase stability

- Higher optical power handling capacity

- Reduced DSP power requirements

- 50-100x higher cost per km than SMF

- Complex and low-yield manufacturing

- Difficult splicing and connectorization

- Higher attenuation than best SMF (in most fibers)

- Bend sensitivity requiring careful handling

- No established ITU-T standards yet

- Limited supplier ecosystem

- Sparse field personnel training

4. Challenges and Disadvantages

Despite its compelling physics advantages, HCF faces several significant practical and economic challenges that currently limit its adoption to specialized, high-value applications.

4.1 Manufacturing Complexity and Cost

Producing HCF is far more complex than manufacturing standard fiber. The process typically involves the "stack-and-draw" method, where precisely dimensioned capillaries and rods are assembled into a preform and then drawn down to fiber dimensions. Achieving nanometer-scale precision and uniformity in the intricate microstructure over kilometer-length continuous draws is technologically demanding. Structural distortions -- variations in hole size, shape, wall thickness, or core boundary -- can significantly degrade fiber performance.

The cost implications are substantial. As of 2025, commercial HCF costs approximately $5-10 per meter, compared to roughly $0.10 per meter for high-volume standard SMF -- a 50 to 100 times cost premium. Only a handful of manufacturers can produce telecommunications-grade HCF, and production volumes remain orders of magnitude below conventional fiber. Microsoft has partnered with Corning and Heraeus Covantics to scale manufacturing, and Chinese manufacturers including YOFC and Linfiber Technology are advancing rapidly, but achieving cost parity with SMF remains years away.

4.2 Splicing and Connectorization

Integrating HCF into existing networks presents a major practical challenge. The hollow core and delicate microstructure make fusion splicing significantly more complex than with solid fiber. Precise alignment of the tiny air core and surrounding capillaries is required, and standard fusion splicing equipment and programs do not work well with HCF. Specialized splicing techniques and connector ferrules have been developed -- Microsoft reports achieving 0.05 dB HCF-to-HCF self-splicing loss and under 0.3 dB hollow-to-solid connections -- but these require specialized training and equipment.

A critical operational concern is cleanliness: any dust or impurities entering the hollow core during termination can dramatically increase loss. Field termination may require cleanroom-like conditions, adding complexity and cost to installation and maintenance.

4.3 Attenuation

While HCF loss has improved dramatically, it remains above the best conventional SMF for most practical deployed fibers. Standard SMF routinely achieves 0.17-0.18 dB/km in production, while commercial HCF cables typically operate at 0.5-1.0 dB/km. Record laboratory results have demonstrated <0.11 dB/km (OFC 2024, DNANF design) and even 0.05 dB/km reported at OFC 2025 by YOFC, breaking through the Rayleigh scattering limit of silica. However, translating laboratory records into consistent, high-yield production fiber at these loss levels remains an ongoing challenge.

Higher attenuation limits unrepeated span distance. euNetworks' commercial London deployment, for example, operates 40 km of end-to-end HCF without mid-span amplification -- impressive, but shorter than what standard fiber can achieve. For long-haul and submarine applications, HCF's current attenuation penalty is a barrier, though this gap is narrowing with each generation of fiber design improvements.

4.4 Bend Sensitivity

The delicate cladding microstructure of HCF makes it more sensitive to bending than conventional fiber. Bending distorts the micro-structured cladding, disrupting the conditions for optimal light guidance (whether PBG or anti-resonance) and increasing leakage loss. Installation requires careful attention to minimum bend radii, and cables must be designed to protect the fiber from mechanical stress during pulling through ducts, bending around corners, and surviving environmental conditions. Modern fiber designs are improving bend resistance by optimizing the ratio between cladding capillary diameter and core diameter (typically 0.6-0.7 for AR-HCF), but this often involves trade-offs with other parameters.

4.5 Standardization Gap

As of 2025, no ITU-T recommendations exist for HCF equivalent to conventional fiber's mature G.652/G.654/G.655/G.657 series. This means there are no standardized fiber specifications, test methodologies, installation procedures, certification programs, or warranty frameworks. Each manufacturer currently produces proprietary, incompatible designs. The lack of industry standards prevents multi-vendor interoperability and makes it difficult for network operators to evaluate, specify, and procure HCF with the same confidence they have for standard fiber. Developing these standards typically requires years of committee work and industry consensus.

Amplification Challenge: Standard Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers (EDFAs) are designed for solid-core fiber and work within the C and L bands. HCF's broader bandwidth potential cannot be fully used until compatible amplification solutions are developed. Raman amplification, which relies on the nonlinear response of the fiber medium, is ineffective in HCF due to its negligible nonlinearity. New amplifier architectures will be needed to exploit HCF's full spectral capacity.

4.6 Gas Ingress and Fiber End Management

One of the most distinctive operational challenges of HCF -- and one that has no equivalent in conventional solid-core fiber -- is the vulnerability of the hollow core to atmospheric gas contamination. This is a well-documented issue that network operators must understand and plan for when deploying HCF links.

The Mechanism: How Contamination Occurs

During the fiber drawing process, the hollow core and cladding voids are typically sealed at elevated temperature under controlled atmospheric conditions. When the fiber is drawn, the internal pressure inside the micro-structured hollow regions is often slightly lower than ambient atmospheric pressure. After fabrication, if the fiber ends are left open or are cut (during cleaving, splicing, or connector preparation), this internal low-pressure environment acts as a weak suction mechanism that draws ambient air into the hollow core from the exposed ends.

Over time -- days, weeks, or months depending on the fiber length and ambient conditions -- atmospheric gases progressively diffuse deeper into the hollow core. The primary contaminants are:

| Gas Species | Source | Absorption Impact | Affected Wavelengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Vapor (H2O) | Atmospheric humidity ingress | Roto-vibrational absorption; increases loss near fiber ends | ~1.37 µm (strong), ~1.87 µm |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO2) | Atmospheric ingress | CO2 absorption lines visible on signal spectrum in lower C-band | ~1.4 µm, ~1.57 µm, ~2.0 µm |

| Hydrogen Chloride (HCl) | Remnants of halogenated precursors used in silica production | Absorption from manufacturing residue | ~1.7-1.8 µm region |

In long-span HCF transmission experiments, CO2 absorption lines have been directly observed on the optical signal spectrum at lower C-band wavelengths. During the record 301.7 km unrepeated transmission demonstration, researchers noted visible CO2 absorption signatures and quantified their impact on transmission performance. OTDR measurements also reveal transient changes in scattering near both ends of an HCF span, caused by gas pressure gradients where atmospheric air has partially diffused into the fiber.

The "Cutback" Solution: Periodic Fiber End Trimming

The practical solution to this gas contamination issue is periodic fiber end trimming, commonly called "cutback." Because gas ingress is a diffusion process that propagates inward from the exposed fiber ends, contamination is concentrated in the first few meters of fiber at each end. By cleaving off a short section (typically 1-5 meters) from each end and re-terminating, the contaminated fiber is removed and the optical performance is restored.

OFS (now Furukawa Electric), the manufacturer of the AccuCore HCF product line, explicitly includes on-site cable trimming as part of their commercial HCF deployment service. Their service package covers indoor/outdoor field-deployable cable, installation support, on-site cable trimming, and both field and factory termination with standard connectors -- acknowledging that periodic end maintenance is a normal part of HCF lifecycle management, not a defect.

Practical Implication: Network planners should factor in a small amount of extra fiber length at each end to accommodate periodic trimming over the link's operational lifetime. For a 20-year deployment, a few extra meters at each termination point provides a consumable margin for maintenance cuts. This is a minor consideration in link design, but it differs fundamentally from SMF, which requires no such end-of-life length management.

Mitigation Strategies

Several approaches are used to minimize gas ingress and extend the interval between required maintenance cuts:

Hermetic Sealing: HCF-to-HCF and HCF-to-SMF splices should provide hermeticity (airtight sealing) to prevent ongoing contamination of the fiber core. Splicing the HCF to solid-core SMF patch tails at each end effectively seals the hollow core, as the solid glass interface blocks further atmospheric ingress. This is why commercial HCF cables are typically terminated with SMF pigtails at both ends.

Inert Gas Fill: Some HCF cable designs use dry nitrogen fill in the hollow core rather than leaving it with ambient air. Nitrogen filling serves dual purposes: it prevents moisture and airborne contaminants from entering, and it slightly reduces Rayleigh scattering compared to humid air. Research is ongoing into optimal gas compositions for different operating environments.

Controlled Cleaving Environment: Cisco's published operational guidelines specifically note that cleaving and splicing of HCF should be conducted in a dust-free, low-humidity environment. The low internal pressure of the fiber acts as a suction that draws in dust and wet air during any open-end operation. A critical prohibition applies: cleaning of a cut but unsealed HCF with liquid solvents (isopropyl alcohol, acetone, etc.) is strictly forbidden, as the solvent would impregnate all voids through capillary action and the fiber would permanently lose its guiding properties.

Long-Term Stability: The Good News

An important distinction must be made: the gas ingress issue affects only the first few meters near exposed fiber ends, not the bulk fiber. Research published at OFC 2022 by Rikimi et al. compared the optical performance of Photonic Bandgap and Anti-Resonant hollow core fibers after long-term exposure to the atmosphere and found that exposed NANF fiber has shown no degradation over time. The anti-resonant fiber design proved inherently stable against atmospheric exposure. This means a properly sealed and spliced HCF link, once installed, maintains stable performance throughout its core length -- the trimming requirement applies only at interfaces where the fiber has been cut and re-exposed.

5. Technology Maturity and Commercial Status

HCF has transitioned from a laboratory curiosity to a commercially validated technology, though its adoption remains concentrated in high-value niche applications. The following timeline captures key milestones in HCF's development and commercialization.

5.1 Key Milestones

First single-mode PBG guidance in air: Cregan et al. demonstrate light guidance in a hollow-core photonic crystal fiber, proving the concept of using photonic bandgap to confine light in air.

PBGF loss record of 1.7 dB/km: Mangan et al. achieve the lowest loss in a photonic bandgap hollow-core fiber, a record that stands for years and shows the technology's potential for telecommunications.

NANF concept proposed: Francesco Poletti at the University of Southampton publishes the Nested Anti-resonant Nodeless Fiber design, which becomes the blueprint for all subsequent record-breaking HCF performance.

Lumenisity founded: University of Southampton spinout established to commercialize NANF-based hollow core fiber, producing the CoreSmart cable solution.

OFS launches AccuCore HCF: First commercially available terrestrial hollow-core fiber cable solution using photonic bandgap technology, targeting high-frequency trading and HPC applications.

euNetworks first commercial HCF deployment: World's first commercial HCF deployment connecting Interxion LON1 data center to the London Stock Exchange, proving commercial viability for latency-sensitive trading.

Microsoft acquires Lumenisity: Strategic acquisition expanding Microsoft's ability to optimize Azure cloud infrastructure. DNANF achieves 0.174 dB/km at OFC 2022 -- the first HCF to approach silica fiber loss levels. Comcast deploys 40 km in Philadelphia (10-400 Gbps bidirectional, 33% latency reduction).

Record loss below 0.11 dB/km: DNANF achieves <0.11 dB/km at 1550 nm and 0.15 dB/km at 1310 nm (OFC 2024 postdeadline). Microsoft begins deploying HCF across Azure data center interconnects, carrying live customer traffic with zero failures.

Commercial expansion accelerates: Microsoft targets 15,000 km deployment by late 2026. YOFC reports 0.05 dB/km at OFC 2025. China Mobile deploys 20 km Shenzhen-Hong Kong commercial link (0.085 dB/km, 30%+ latency optimization). Relativity Networks secures $4.6M funding for AI data center interconnect. euNetworks deploys "longest ever" HCF segment exceeding 40 km to Euronext in Bergamo, Italy. Navigation-grade fiber optic gyroscope demonstrated with 29.4x improvement over previous HCF gyroscopes.

5.2 Current Market Reality

As of 2025, HCF serves under 0.1% of global fiber installations. It remains a technology with clear technical superiority in specific performance dimensions -- latency, nonlinearity, bandwidth -- but with cost and ecosystem barriers that prevent mainstream displacement of conventional SMF. The technology is best described as commercially validated in niche applications with a credible pathway to broader adoption over the next 5-10 years.

Key suppliers include Microsoft (NANF/DNANF, leading deployment scale), OFS (AccuCore PBG-based, commercial product), Relativity Networks (ARF, co-manufacturing with Prysmian), Exail (ARF, industrial applications), and YOFC/Linfiber Technology (ARF, Chinese market).

Figure 6: Evolution of hollow core fiber attenuation records at 1550 nm. Recent DNANF designs have broken through the fundamental Rayleigh scattering limit of silica fiber (~0.14 dB/km), achieving 0.05 dB/km as of OFC 2025.

6. Hollow Core Fiber vs. Standard Single-Mode Fiber

| Parameter | Hollow Core Fiber (HCF) | Standard SMF (G.652/G.654) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Medium | Air / vacuum | Solid silica glass |

| Guiding Mechanism | Photonic bandgap or anti-resonant reflection | Total internal reflection |

| Latency | ~3.34 µs/km (near speed of light in vacuum) | ~4.89 µs/km |

| Attenuation (production) | 0.5-1.0 dB/km typical; lab record: <0.11 dB/km | 0.17-0.18 dB/km (production); limit: ~0.14 dB/km |

| Chromatic Dispersion | <2-3 ps/nm·km | ~17 ps/nm·km at 1550 nm |

| Nonlinear Effects | Negligible (~1,000x lower than SMF) | Significant at high power (SPM, XPM, FWM, SBS) |

| Usable Bandwidth | Ultra-wide: continuous O through L+ band (>400 nm); no water peak; can be designed for visible through mid-IR | Limited by silica properties; ~100 nm optimized (C+L); water peak in legacy E-band fiber |

| Power Handling | Much higher (reduced nonlinearity and damage threshold) | Limited by nonlinear effects and damage threshold |

| Physical Security | Inherently tamper-detectable | Can be tapped without easy detection |

| Phase Stability | 20-30x better than SMF | Baseline |

| Cost per km | $5-10 per meter (50-100x premium) | ~$0.10 per meter |

| Maturity | Early commercial; limited vendors and standards | Fully mature; billions of km deployed globally |

| Splicing | Complex; specialized equipment required | Routine; well-established procedures |

| Fiber End Management | Periodic cutback required (gas ingress at exposed ends); solvent cleaning prohibited | No special end management; standard cleaning procedures apply |

7. Best Use Cases for Hollow Core Fiber

HCF's current cost-performance profile makes it most compelling in applications where its unique physical properties provide value that clearly justifies the cost premium. The technology is following a classic adoption trajectory: beginning in high-value niche markets and gradually expanding toward broader deployment as manufacturing scales and costs decrease.

The earliest and most established commercial application. Trading firms gain competitive advantage from microsecond latency reductions between exchanges and data centers. euNetworks' London deployment connects the London Stock Exchange, ICE Basildon, and multiple financial data centers with 30%+ latency reduction over conventional fiber.

3 µs/km round-trip saving | 30%+ latency reductionHCF enables data centers to be placed farther apart without performance penalties, expanding the viable "latency envelope" from ~60 km to ~90 km radius -- a 2.25x increase in available geographic area. This allows hyperscalers to access cheaper land, more sustainable power, and favorable climates for AI infrastructure.

90 km DCI reach vs. 60 km SMF | 2.25x area expansionMicrosoft is deploying HCF across Azure to accelerate east-west traffic between servers and between regional clusters. Reduced latency improves distributed AI model training efficiency and real-time cloud service performance. Microsoft targets 15,000 km of HCF deployment by late 2026.

15,000 km target by 2026 | Zero-failure operationsHCF's intrinsic tamper-detection capability makes it valuable for secure government communications. Any physical intrusion causes detectable signal changes, enabling real-time security monitoring at the physical layer -- a property conventional fiber cannot match.

Real-time intrusion detection | Enhanced physical securityNext-generation mobile networks require ultra-low latency connections between antennas and centralized baseband units. HCF's reduced propagation delay improves network responsiveness. China's Guangdong Province deployed over 8,000 km for 5G+ industrial internet with 18% reduction in base station energy consumption.

18% energy reduction | Sub-ms latency improvementHCF's 20-30x better phase stability, 170x reduced Kerr effect, and 20x reduced Faraday effect make it ideal for precision inertial navigation. A 2025 demonstration achieved navigation-grade performance with 29.4x improvement over previous HCF gyroscopes.

Navigation-grade accuracy | 170x Kerr reductionHCF's superior phase stability and reduced environmental sensitivity enable more stable quantum channels over longer distances, advancing the practical deployment of quantum-secure communication networks.

20-30x phase stability improvementKeeping intense light out of glass avoids nonlinear distortion and damage. HCF can transport kilowatt-scale continuous laser powers for industrial machining, medical procedures, and glass cutting for smartphones -- applications where solid-core fibers cannot compete.

kW-scale power delivery | Zero glass damage8. Practical Deployment Considerations

8.1 Hybrid Network Architecture

The most practical near-term deployment approach is hybrid: using HCF selectively on the most latency-sensitive or performance-critical segments while retaining conventional SMF elsewhere. This has been proven in commercial deployments -- euNetworks' London network uses a 45 km hybrid route combining HCF and SMF segments, running 10% faster than an equivalent all-SMF route. HCF and SMF can be spliced and coexist in the same network, with HCF-to-SMF connectorized patch tails providing the interface between the two fiber types.

Figure 5: Hybrid HCF/SMF network deployment architecture showing HCF on the latency-critical DCI path and standard SMF on the secondary route, with DWDM compatibility at both data center ends.

8.2 Installation and Handling

Microsoft has demonstrated that HCF can be installed using standard cable installation practices -- blowing cable through pre-installed conduit using high-pressure air, with re-fleeting and re-jetting at access chambers. Purpose-designed cable joint enclosures protect HCF splices underground. Inside data centers, connectorized "plug-and-play" HCF-specific patch tails interface with existing DWDM equipment. However, technicians require specialized training on the nuances of HCF handling, and the fiber demands more careful treatment during installation than conventional cable.

8.3 Testing and Monitoring

Standard Optical Time Domain Reflectometers (OTDRs) need adaptation for HCF, as the fiber's low backscatter characteristics (desirable for performance) make conventional OTDR measurements challenging. Microsoft has developed custom HCF OTDR solutions for fault location. Ultra-high resolution and long-range Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry (OFDR) techniques are being explored for detailed HCF characterization and monitoring. Additionally, standard optical spectrum analyzers and coherent transponders work with HCF, enabling compatibility with existing DWDM systems for multi-Tb/s capacity delivery.

9. Future Outlook

The trajectory for HCF over the 2025-2030 period suggests continued dominance in specialized applications with gradual expansion into broader markets, driven by several converging trends.

Manufacturing Scale-Up: Microsoft's partnerships with Corning and Heraeus Covantics represent critical steps toward volume production. The Romsey facility has demonstrated production-grade continuous lengths over 15 km with specifications maintained end-to-end. Chinese manufacturers' rapid progress provides alternative commercialization pathways and competitive pressure that should accelerate cost reductions.

Loss Reduction Continuing: The fundamental limits of the newest HCF fibers are still unknown. Loss continues to drop as fabrication techniques improve. Researchers speculate that in a few years, new hollow-core fibers might be ten times clearer than the fundamental limit of solid-core fibers at shorter wavelengths.

Standardization Progress: While no ITU-T standards exist yet, the growing commercial deployment base and multi-vendor ecosystem are creating the conditions for standardization work to begin. Establishing test methodologies, fiber specifications, and installation guidelines is essential for the technology to scale beyond current specialist deployments.

New Application Frontiers: Beyond current deployments, HCF is expanding into quantum communications, precision navigation for aerospace and autonomous vehicles, chemical and gas sensing (exploiting the hollow core's ability to contain sample gases for optical interrogation), and medical laser delivery systems.

The Bottom Line: HCF is not a replacement for conventional fiber -- it is a complementary technology that excels in specific performance dimensions. The future of optical networking will likely be hybrid, with HCF strategically deployed where its physics advantages produce the most value. As manufacturing scales, costs decrease, and standards develop, the range of applications where HCF makes economic sense will steadily expand.

10. Conclusion

Hollow Core Fiber represents one of the most significant technological advances in optical fiber since the development of low-loss silica fiber in the 1970s. By replacing glass with air as the light-guiding medium, HCF breaks through fundamental physical barriers that have constrained optical networking for decades: the speed of light in glass, nonlinear signal degradation, and Rayleigh scattering limits.

The technology's advantages are real and proven in commercial deployments. A ~31% latency reduction, ~1,000-fold lower nonlinearity, broader usable bandwidth, ultra-low chromatic dispersion, enhanced physical security, and superior phase stability create a compelling set of properties that no incremental improvement to conventional fiber can match.

Equally real are the challenges. A 50-100x cost premium, complex manufacturing, difficult splicing, absence of industry standards, and a limited vendor ecosystem restrict HCF to high-value niche markets where its performance gains justify the investment. High-frequency trading, AI data center interconnects, hyperscale cloud infrastructure, and precision sensing are the applications driving current adoption.

The path forward is clear: continued loss reduction through advanced fiber design, manufacturing scale-up through strategic partnerships, ecosystem development through standardization, and market expansion as costs decrease. HCF will not replace conventional fiber overnight, but it is establishing itself as an indispensable tool in the optical networking toolkit -- enabling a new generation of applications built on the foundation of light-speed connectivity through air.

References

- ITU-T Recommendation G.652 -- Characteristics of a single-mode optical fibre and cable.

- F. Poletti, "Nested antiresonant nodeless hollow core fiber," Opt. Express 22, 23807-23828 (2014).

- G. T. Jasion et al., "0.174 dB/km Hollow Core Double Nested Antiresonant Nodeless Fiber (DNANF)," OFC 2022, Postdeadline Paper Th4C.7.

- Y. Chen et al., "Hollow Core DNANF Optical Fiber with <0.11 dB/km Loss," OFC 2024, Postdeadline Paper Th4A.8.

- E. N. Fokoua et al., "Loss in hollow-core optical fibers: mechanisms, scaling rules, and limits," Adv. Opt. Photonics 15, 1-85 (2023).

- Microsoft Azure Blog, "How hollow core fiber is accelerating AI."

- Microsoft Official Blog, "Microsoft acquires Lumenisity, an innovator in hollow core fiber (HCF) cable."

- euNetworks, "euNetworks deploys Lumenisity Hollow-core Fibre in London."

- OFS, "AccuCore HCF Fiber Optic Cable Assembly" -- Product documentation.

- H. Sakr et al., "Hollow core optical fibres with comparable attenuation to silica fibres between 600 and 1100 nm," Nat. Commun. 11, 6030 (2020).

- C. Forster, J. Gaudette, F. Rey, T. Pearson, R. Ellis, C. Badgley, and A. Saljoghei, "The Deployment of Hollow Core Fiber," Microsoft TechCommunity.

- S. Rikimi et al., "Comparison between the Optical Performance of Photonic Bandgap and Antiresonant Hollow Core Fibers after Long-Term Exposure to the Atmosphere," OFC 2022.

- K. Borzycki et al., "Hollow-Core Optical Fibers for Telecommunications and Data Transmission," Recent Developments, Emerging Trends and Technologies for Optical Networks.

- E. N. Fokoua et al., "Advances in hollow-core fiber for the 1 mm and visible," Optics Letters (2023).

- T. Bradley et al., "Unrepeated HCF Transmission over spans up to 301.7 km," OFC 2025.

- Cisco Systems, "Hollow Core Fiber -- Operational Considerations," BRKMSI-2006, Cisco Live 2025.

- Sanjay Yadav, "Optical Network Communications: An Engineer's Perspective" -- Bridge the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Optical Networking. Available on Amazon

Developed by MapYourTech Team

For educational purposes in Optical Networking Communications Technologies

Note: This guide is based on industry standards, best practices, and real-world implementation experiences. Specific implementations may vary based on equipment vendors, network topology, and regulatory requirements. Always consult with qualified network engineers and follow vendor documentation for actual deployments.

Feedback Welcome: If you have any suggestions, corrections, or improvements to propose, please feel free to write to us at feedback@mapyourtech.com

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here