19 min read

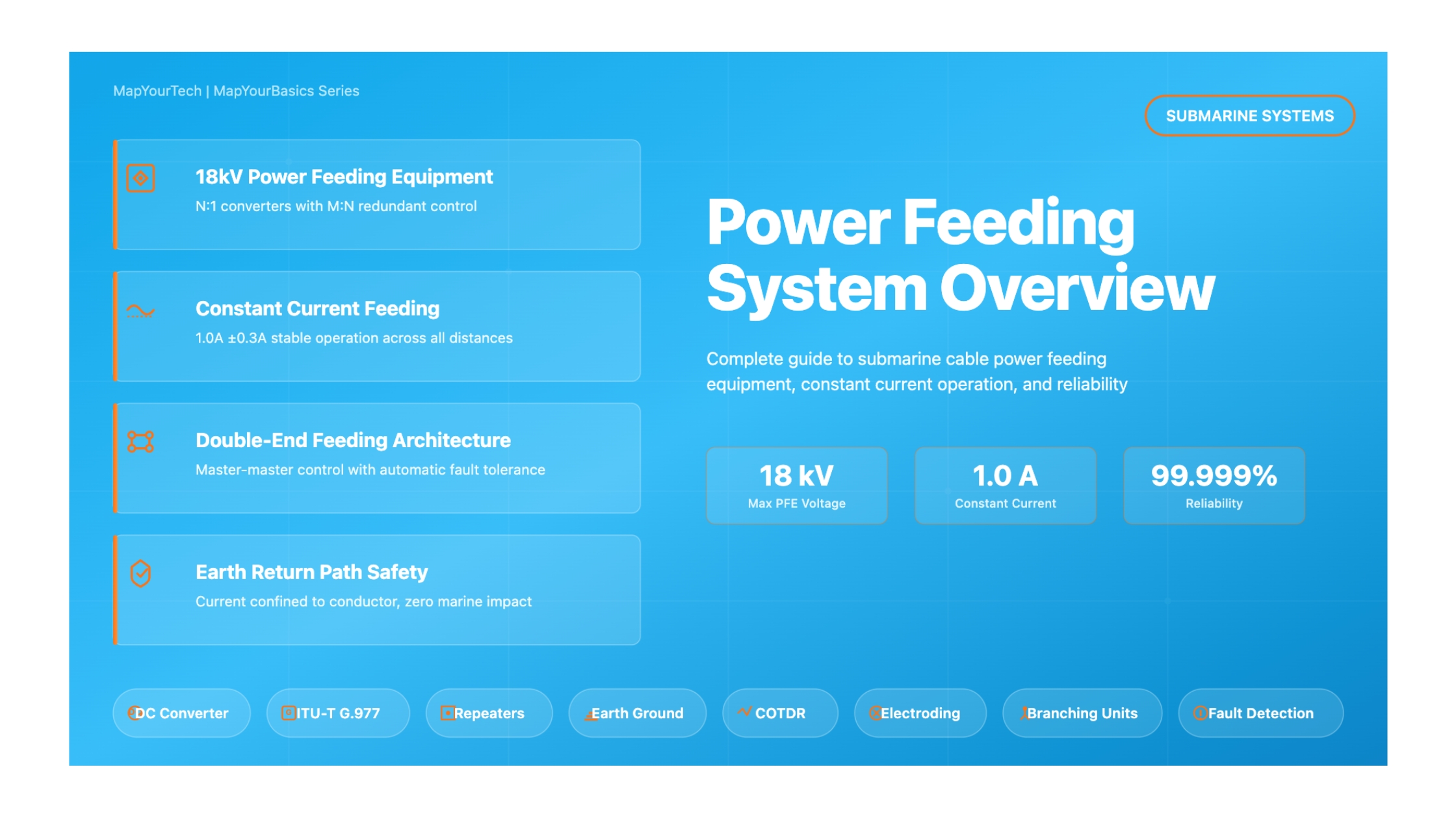

Power Feeding System Overview

Power Feeding Equipment (PFE)

1. Introduction

Power feeding systems are the lifeblood of submarine cable networks, providing the essential electrical power required to operate optical amplifiers and repeaters across vast ocean distances. These systems represent a critical component of the global telecommunications infrastructure, enabling continuous high-speed data transmission that connects continents and supports modern digital communications.

In submarine cable systems, Power Feeding Equipment (PFE) installed at terminal stations supplies constant direct current through the metallic conductor of the cable to energize submerged repeaters connected in series along the system. The electrical circuit is completed via a return path through the earth and sea, with each PFE unit connected to earth to complete this circuit. This constant current power feeding architecture ensures stable repeater characteristics and optimal transmission performance across the entire cable length.

System Overview: Complete Power Feeding Architecture

End-to-end submarine cable system showing power feeding from shore stations through underwater repeaters

Key Concept: Power feeding to submarine cable systems is a well-established practice that has evolved from coaxial submarine systems to modern optical amplifier systems. The fundamental principle remains consistent: constant DC current is fed through the cable's inner conductor to power repeaters, while seawater and earth provide the return path.

1.1 Why Power Feeding Systems Matter

Modern submarine cable systems span thousands of kilometers across ocean floors, requiring optical amplifiers (repeaters) positioned every 50-100 km to maintain signal strength. Without reliable power feeding, these repeaters cannot function, making power feeding systems absolutely essential for:

- Global Connectivity: Submarine cables carry over 99% of international data traffic, supporting internet, telecommunications, and financial transactions worldwide

- System Reliability: Power feeding equipment must maintain continuous operation for 25+ years with extremely high availability requirements

- Capacity Expansion: Modern DWDM systems require increased power feeding current to support higher numbers of transmission wavelengths

- Cost Efficiency: Proper power feeding design enables longer cable segments and fewer power feed points, reducing infrastructure costs

1.2 Real-World Applications

Power feeding systems serve critical functions across various submarine cable applications:

- Transoceanic Communications: Systems like transpacific cables spanning 9,000+ km require sophisticated power feeding with voltages up to 18 kV

- Regional Networks: Shorter systems connecting neighboring countries utilize optimized power feeding configurations

- Scientific Observatories: Underwater sensor networks require both constant current and constant voltage power feeding options

- Offshore Applications: Oil and gas platforms and offshore wind farms depend on reliable submarine power transmission

2. Historical Context & Evolution

The evolution of power feeding systems parallels the advancement of submarine cable technology itself, progressing from simple coaxial systems to sophisticated optical amplifier networks. Understanding this historical context provides valuable insights into current design practices and future development directions.

Evolution Timeline: Power Feeding Technology

Key milestones in submarine cable power feeding development

2.1 Early Development Period (1960s-1980s)

The coaxial submarine cable era established fundamental power feeding principles that remain relevant today. These early systems employed regeneration, reshaping, and retiming (3R) technology with typical feeding currents of 1.6A ± 0.2A. Power feeding equipment during this period was limited to approximately 8 kV maximum voltage for transpacific systems, constraining system length and requiring multiple power feed points for long-distance cables.

2.2 Optical Revolution (1988-2010)

The introduction of optical fiber submarine cables marked a significant shift in power feeding requirements. Early optical systems like TPC-3 (Japan-Guam-Hawaii) demonstrated the viability of trunk-and-branch configurations with local power feeding at branching points. This period saw the transition to optical amplifier systems, which required lower feeding currents (typically 1.0A ± 0.3A) compared to regenerative systems, enabling more efficient power utilization.

2.3 Modern DWDM Era (2010-Present)

Dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) systems introduced new power feeding challenges and opportunities. The dramatic increase in transmission capacity required higher power consumption to support multiple wavelengths, leading to increased feeding currents. Enhanced PFE designs now generate voltages exceeding 15 kV, with current systems reaching 18 kV, enabling single-end feeding capability for the longest transpacific cable systems.

2.4 Future Outlook

Based on current industry trends and recent developments, several key advancements are shaping the future of power feeding systems:

- Higher Voltage Capabilities: Industry leaders are pushing beyond 18 kV to support ultra-long distance systems and increased capacity demands

- Improved Efficiency: Advanced power conversion technologies are reducing losses and improving overall system efficiency

- Enhanced Reliability: Redundancy architectures and fault tolerance mechanisms continue to evolve, targeting even higher availability

- Smart Monitoring: Integration of advanced monitoring and control systems enables predictive maintenance and optimization

- Portable Solutions: New portable PFE designs facilitate repair operations and temporary installations

3. Core Concepts & Fundamentals

Understanding the fundamental principles of power feeding systems requires grasping several interconnected concepts that govern their design and operation. These core principles ensure reliable, efficient power delivery across thousands of kilometers of submarine cable.

3.1 Constant Current Power Feeding Principle

The cornerstone of submarine cable power feeding is the constant current approach. PFE units maintain a stable DC current regardless of cable length or component variations. This design choice offers several critical advantages:

- Stable Repeater Operation: Constant current ensures consistent voltage drop across each repeater, maintaining stable amplification characteristics

- Automatic Fault Balancing: In the event of a shunt fault, the system automatically balances around the fault point

- Reduced Voltage Stress: Not all cable sections experience maximum voltage, reducing dielectric breakdown risk

- Simplified Design: Repeaters can be designed for a specific current requirement without complex voltage regulation

Constant Current Operation Principle

How constant current power feeding maintains stable repeater operation

3.2 Power Feeding Budget Components

The power feeding budget aggregates all voltage drops along the electrical path and confirms PFE specifications. Understanding each component is essential for proper system design:

Power Feeding Budget Components

Complete voltage budget showing all contributing factors (based on ITU-T standards)

| Budget Component | Description | Typical Values |

|---|---|---|

| PFE Impedance | Internal voltage drop within power feeding equipment | Varies by design |

| Submarine Cable | Resistance proportional to cable length and temperature | Temperature-dependent |

| Repeater Voltage Drop | Voltage drop across each repeater or branching unit | 1-3 kV per unit |

| Land/Earth Cable | Resistance of shore-side cable sections | Minimized in design |

| Earth Ground Resistance | Resistance of earth electrode connection | < 3Ω recommended |

| Earth Potential Difference | Natural voltage between PFE earth connections | ~0.1 V/km nominal |

| Repair Margin | Additional capacity for future cable/repeater additions | 10-20% typical |

3.3 Power Feeding Current Requirements

The power feeding current is derived from repeater current requirements to maintain stable amplification. For modern optical amplifier systems, current distribution within a repeater typically follows this pattern:

| Parameter | Proportion | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Pump Laser Diode Current | 80% | Includes ~10% end-of-life margin |

| Control Circuit Current | 10% | Monitoring and regulation circuitry |

| Electroding Margin | 10% | 80 mA margin for in-service electroding |

Historical Comparison: Early 3R systems required 1.6A ± 0.2A, while optical amplifier systems operate at 1.0A ± 0.3A. Recent DWDM systems have seen increased current requirements due to higher wavelength counts, but advances in pump laser efficiency help contain this growth.

3.4 Earth Potential Difference

The power feeding circuit forms a complete loop with return path through earth and sea. Earth potential difference (EPD) between terminal stations must be considered in voltage calculations. This phenomenon arises from:

- Earth's Magnetic Field: Movement of Earth's mantle creates potential differences

- Solar Activity: 11-year sunspot cycles can cause magnetic storms affecting EPD

- Geographic Location: Higher latitudes experience greater EPD variations

Design guidelines specify approximately 0.1 V/km for EPD in typical specifications, though ITU-T Recommendation G.977 suggests up to 0.3 V/km based on historical experience. Notable events include the March 1989 magnetic storm that produced 700V EPD on the TAT-8 cable (5,066 km), equivalent to 0.138 V/km.

Design Consideration: Since PFE operates in constant DC current output mode, extraneous voltages caused by magnetic field changes are automatically corrected through output voltage adjustment, as long as the change remains within the PFE's voltage range.

4. Technical Architecture & Components

A complete power feeding system comprises multiple integrated components working together to deliver reliable, constant current power across the entire submarine cable network. Understanding the architecture and individual component functions is essential for system design and operation.

4.1 Power Feeding Equipment (PFE) Architecture

PFE Functional Block Diagram

Complete power feeding equipment architecture

4.2 PFE Component Functions

Power Regulator Unit: Comprises multiple power generation (converter) units connected in series to generate the required voltage at the specified current. The converters employ N:1 redundancy protection, ensuring operation continues even if individual converter units fail. Modern PFE systems can generate voltages exceeding 18 kV through series connection of multiple converter modules.

Control Unit: Continuously detects generated current and voltage, sending control signals to each converter to maintain specified values. M:N protection is employed for controller redundancy. The control unit performs:

- Precise current control with master-master coordination between geographically separate PFEs

- Voltage limitation to prevent exceeding specified maximum values

- Slow ramp-up/down control to avoid large surge currents

- Safety monitoring and automatic shutdown functions

Load Transfer Unit: Switches the PFE output between the submarine cable line and a test load unit. The low-pass filter smooths voltage ripple and provides impedance matching. This unit enables standalone PFE testing without connecting to the cable plant.

Earth Switching Unit: Switches the system earth connection from sea earth to station earth if degradation of the sea earth is detected. The automatic changeover capability ensures continuous operation even during earth electrode issues. Dual earth paths provide critical redundancy for the current return circuit.

4.3 PFE Required Functions

PFE Essential Functions

Key operational capabilities required in modern power feeding equipment

Electroding Function Details: This function helps cable ships locate and identify cables for maintenance. An electroding tone (4-50 Hz low-frequency signal) is applied to the cable. In-service mode uses ±80 mA superposed on normal current with no traffic effect. Out-of-service mode uses ±160 mA, detectable over 500 km with 10 mA signal strength.

4.4 System Redundancy Architecture

Power feeding systems implement multiple layers of redundancy to achieve extremely high reliability:

System Redundancy: Double-end power feeding configurations use master-master current control. Line current is maintained at desired value through automatic voltage adjustment at each PFE, continuing operation even if a cable fault occurs or one PFE develops issues.

Equipment Redundancy: Single-end power feeding (typically for branch stations) uses distinct working and standby PFE units. While unable to maintain operation during cable faults, equipment redundancy ensures continued operation if one PFE unit fails completely.

Parts Redundancy: Key subsystems within each PFE are duplicated:

- Power converter units with N:1 protection

- Current/voltage detection packages

- Current/voltage controller packages with M:N protection

- Dual earth return current paths (sea earth and station earth)

Path Reconfiguration: Branching units enable power feeding path reconfiguration, providing additional fault tolerance and maintenance flexibility. The combination of these redundancy features achieves overall power feeding system reliability approaching five-nines (99.999%) availability.

5. Powering Topologies

The power feeding topology depends on the overall submarine cable system configuration and determines how electrical power is distributed to repeaters throughout the network. Two main categories exist: point-to-point topology and trunk-and-branch topology, each with specific characteristics and applications.

5.1 Point-to-Point Topology

Point-to-Point Power Feeding Configuration

Double-end feeding with voltage balancing

Point-to-point topology represents the traditional and simplest configuration for submarine cable power feeding. In this architecture:

- Double-End Feeding: PFE units at both terminals supply power simultaneously, with each applying equal but opposite voltages to achieve highest reliability

- Voltage Balancing: The zero voltage point ideally occurs at the cable midpoint, distributing voltage stress evenly

- Fault Tolerance: If one PFE fails, the other can power the entire system in single-ended configuration

- Shunt Fault Handling: Both PFEs automatically adjust voltage levels so the zero voltage point coincides with the fault location, maintaining system operation

Design Constraint: Maximum line voltage must not exceed the lowest withstand voltage among all system components (repeaters, BUs, cables, joint boxes, PFE). If initial design exceeds any withstand voltage, redesign is necessary through current reduction or system segmentation.

5.2 Trunk-and-Branch Topology

Trunk-and-Branch Topologies

Star, fishbone, and branch-on-branch configurations

Trunk-and-branch topologies enable connection of multiple landing points using branching units, allowing cost-effective connectivity for many cities and communities. Three main variants exist:

Star Application: Basic trunk-and-branch configuration connecting three landing points. The trunk cable is powered from both end stations, while the branch is powered by local PFE feeding to a sea earth at the BU. Power feeding can be reconfigured such that a cable fault on one segment doesn't affect other segments.

Fishbone Application: Each branch cable connects directly to the trunk. Multiple BUs along the trunk enable connections to several branch stations. This topology provides good capacity distribution while maintaining reasonable complexity.

Branch-on-Branch Application: Branches are concatenated, with secondary BUs on primary branch cables. This hierarchical approach enables capacity allocation between parties consistent with optimized physical connections for economical solutions.

Critical Design Rule: In trunk-and-branch topology, the polarity of branch segment PFE feeding to the BU sea-earth must be negative to avoid elution of the BU's sea earth electrode by electrolysis. This requirement stems from Faraday's law governing electrode mass loss.

5.3 Branching Unit Power Reconfiguration

Switchable BUs enable power feeding path reconfiguration to maintain connectivity during faults or maintenance. Key reconfiguration capabilities include:

- Fault Isolation: When trunk cable fault occurs, power path switches to allow double-end feeding of branch to the other trunk side, or single-end feeding of branch to BU and other trunk to BU

- Hot Switching Prevention: Reconfiguration sequences avoid hot switching through current-limiting resistor banks and careful coordination

- Multi-BU Coordination: Complex systems with multiple BUs require tight coordination among terminal stations, typically supported by computerized powering support systems

- Current Control Method: BU switching operates by controlling PFE ramp-up sequence at each station to inject specified small currents into each BU leg

Electrode Elution Calculation: Using Faraday's law, if a PFE operates in positive power feeding mode toward a copper BU sea earth at 1A current, after one year the elution mass will be approximately 21 kg. Since typical BU sea earth electrodes are ~25 kg, positive power feeding toward BUs must be limited to within one year accumulated time during system life.

6. Fault Handling and Localization

Fault detection and localization capabilities are essential for maintaining submarine cable system reliability. Power feeding systems include sophisticated mechanisms for identifying, locating, and managing various fault conditions while minimizing service disruption.

6.1 Shunt Fault Behavior

Shunt Fault Response Characteristics

Current and voltage behavior during and after shunt fault occurrence

When a shunt fault occurs, the power feeding system responds through several phases:

Initial Phase (0-5 seconds): Current continuity is temporarily interrupted. The magnitude of interrupted current relates to distance from the shunt fault point. Surge current at the fault point may exceed 100A due to short circuit of cable charged capacitance, with peak current limited by sea ground resistance and cable resistance.

Adjustment Phase (5-30 seconds): Both PFEs in double-ended configuration automatically adjust voltages to re-establish current flow. Adjustment time depends on power feeding line length and potential difference magnitude, as the cable acts as a low-pass filter in the power feeding line.

Steady State: PFEs stabilize with zero voltage point at the fault location. System remains operational with repeaters on both sides of the fault continuing to function normally. The surge protection circuit in repeaters and BUs enables current flow >200A for long pulses and 450A/15kV for short pulses to bypass surge current.

6.2 Fault Localization Methods

| Method | Fault Type | Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitance Measurement | Open Fault | Entire System | ±1 repeater span |

| DC Resistance Measurement | Shunt Fault | Entire System | High (with master table) |

| Pulse Echo Test | Shunt/Open | <20 km from access | Very High |

| COTDR | Fiber Break | Beyond Repeaters | Excellent |

| Electroding | Shunt Fault | >500 km | Pinpoint Location |

DC Resistance Measurement: Most common method for shunt faults. The length between PFE and shunt fault point is calculated using:

L = (V₀ - ΣV_rep - V_pfe - V_earth - V_difference) / (R_cable × i₁)

Where practical implementation uses a master reference table reflecting system design and commissioning test data for quick fault location.

Electroding: Enables cable ships to locate and identify cables for maintenance. A low-frequency signal (4-50 Hz) is applied from the terminal station to the cable shunt fault point. The cable ship trailing a magnetic sensor detects this signal through multiple passes to pinpoint the fault location. In-service mode (±80 mA) has no effect on traffic, while out-of-service mode (±160 mA) can be detected over 500 km with 10 mA signal strength.

7. Safety & Environmental Protection

One of the most common questions about submarine cable power feeding systems concerns safety: "With thousands of volts and constant current flowing through cables on the ocean floor, why isn't this dangerous to marine life, divers, or ships?" The answer lies in the fundamental principles of electrical circuit design and the physical properties of seawater.

7.1 Why High Voltage is Not a Hazard to Marine Life

Current Flow and Safety Principles

Understanding why submarine cables are safe despite high voltages

The fundamental safety principle is simple: current flows only through the copper conductor inside the cable, never through the surrounding seawater. Here's why:

Closed Circuit Operation: The power feeding system operates as a closed electrical circuit. Current flows from PFE through the cable's copper conductor to the repeaters and returns through the same conductor (or parallel conductor in some designs) back to the earth electrode at the terminal station. The seawater is NOT part of the normal current path along the cable route.

7.2 Multiple Protection Layers

Submarine cables are engineered with multiple concentric layers specifically designed to contain electrical current and protect against environmental hazards:

| Layer | Material | Primary Function | Voltage Withstand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Conductor | Copper tube | Carries DC power current (1.0A typical) | N/A |

| Primary Insulation | Cross-linked polyethylene | Primary electrical insulation | >20 kV |

| Secondary Insulation | Additional polymer layers | Redundant electrical protection | >15 kV |

| Steel Wire Armor | High-strength steel | Mechanical protection, grounded | Grounded shield |

| Outer Sheath | Polyethylene or polypropylene | Water barrier, abrasion protection | N/A |

These layers ensure that even if the outer sheath is damaged by fishing activities or anchor dragging, multiple redundant insulation barriers remain intact. The design withstand voltage typically exceeds the maximum operating voltage by a factor of 1.5 to 2.0 for safety margin.

7.3 Understanding Current vs. Voltage Hazard

A common misconception is that high voltage automatically means high danger. However, electrical hazard depends on current flow through a body, not voltage alone:

Why There's No Shock Hazard from Intact Cables:

- No Current Path: For electric shock to occur, current must flow through the body. Since the cable is completely insulated and current stays inside the conductor, there is no path for current to reach marine life or divers

- Voltage is Relative: The high voltage (up to 18 kV) exists only between the cable's inner conductor and earth ground. The cable's outer surface is at seawater potential (essentially zero voltage relative to the surrounding environment)

- Current Magnitude: Even if insulation were somehow breached, the total system current is only 1.0A - this is limited by the PFE constant current design and is spread over the entire cable length

- Seawater Conductivity: Seawater is a relatively good conductor. Any hypothetical current leakage would disperse over a huge volume, resulting in negligible current density

What Happens During a Cable Fault: Even in the case of a shunt fault (where cable damage exposes the conductor to seawater), the safety systems activate within seconds. The constant current design causes the PFE to automatically adjust voltages to balance around the fault point. The surge current is momentary (typically <5 seconds) and localized to the immediate fault area. Marine life meters away experiences no current flow.

7.4 Earth Return Current and Ocean Ground Beds

The return current path is often a source of confusion. Here's how it actually works:

Earth Return Current Path

How return current flows safely without affecting marine environment

Critical Understanding: The return current path is through deep geological earth layers, NOT through the ocean water where the cable lies. Here's the detailed explanation:

- Earth Electrodes at Terminals Only: Ocean ground beds (sea earth electrodes) are installed only at the terminal stations, not along the cable route. Current enters/exits the earth only at these specific points

- Deep Earth Path: Return current flows through geological earth layers (rock, sediment, earth's crust) following the path of least resistance between the two terminal earth electrodes

- Current Density: The return current (1.0A) spreads over an enormous cross-sectional area through the earth. Current density becomes infinitesimally small - typically nanoamperes per square meter at any given point

- Ocean Water Not in Path: The ocean water along the cable route carries essentially ZERO current. The cable acts as a direct wire connection, while earth provides the distant return path

7.5 Marine Life and Environmental Safety Studies

Extensive environmental studies and decades of operational experience demonstrate that submarine cable power feeding systems pose no hazard to marine ecosystems:

Scientific Evidence:

- Electromagnetic Field Studies: The DC magnetic field around submarine cables is extremely weak (microtesla range) and does not affect marine animal navigation or behavior. Many species use Earth's natural magnetic field (much stronger) for navigation without issue

- Temperature Effects: Cable power dissipation is minimal (I²R losses are small with 1A current). Temperature rise at the cable surface is typically less than 1°C, undetectable in the ocean environment

- Fish Behavior Studies: Long-term monitoring shows no changes in fish behavior, migration patterns, or population density near submarine cables

- Electroreception in Sharks: While sharks can detect electric fields, the zero current flow in surrounding water means there are no detectable electric fields for them to sense from intact, operating cables

Decades of Safe Operation: Submarine cable systems have been operating for over 50 years with hundreds of thousands of kilometers of cable deployed worldwide. There has never been a documented case of marine life injury or environmental harm from the electrical power feeding systems during normal operation.

7.6 Safety for Divers and Marine Operations

For human activities near submarine cables:

Diver Safety:

- Normal Operations: Divers can safely work near or even touch intact submarine cables without any electrical hazard. The cable's outer surface is at seawater potential with no voltage difference to the surrounding environment

- During Repairs: When cables are intentionally cut for repair, power is shut down first. Cable ships follow strict procedures to discharge stored energy before cutting

- Accidental Contact: Even if a cable were somehow damaged while energized, the insulation layers and fault protection systems prevent current from reaching the water

Ship Safety:

- Anchor Strikes: While anchor dragging can damage cables mechanically, there is no electrical shock hazard. The automatic fault detection systems activate immediately if conductor exposure occurs

- Fishing Operations: Trawler nets contacting cables experience no electrical effects. Cable burial in shallow waters provides mechanical protection

7.7 Regulatory Compliance and Standards

Submarine cable power feeding systems must comply with international safety standards:

| Standard | Organization | Key Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| ITU-T G.977 | International Telecommunication Union | Power feeding voltage limits, earth potential difference specifications |

| IEC 60287 | International Electrotechnical Commission | Cable current rating, temperature rise calculations |

| IEC 60840 | International Electrotechnical Commission | Insulation requirements for submarine power cables |

| ICPC Recommendations | International Cable Protection Committee | Environmental protection, route planning, marine safety |

Summary - Why Submarine Cable Power Feeding is Safe:

- Current flows ONLY inside the insulated copper conductor, never in seawater along the cable

- Multiple layers of high-voltage insulation completely contain electrical energy

- Return current uses deep earth geological path, not ocean water

- Constant current design (1.0A) limits total energy even in fault conditions

- Automatic fault detection and voltage adjustment protect against damage scenarios

- 50+ years of safe operation with zero documented marine life impacts

- Cable outer surface is at seawater potential - no voltage difference to environment

- International standards ensure environmental safety and regulatory compliance

8. Latest Developments & Market Trends

The submarine cable power feeding industry continues to evolve rapidly, driven by increasing global data demands, technological advances, and expanding applications beyond traditional telecommunications.

8.1 Current Market Landscape (2024-2025)

The global submarine cables market has experienced substantial growth, with market size estimated at USD 31.70 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 44.33 billion by 2030, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.6% from 2025 to 2030. This growth is significantly driven by rising investments in offshore wind farms and increasing data traffic fueled by over-the-top (OTT) provider demands.

Dry Plant Market Dominance: Dry plant products, including power feeding equipment, monitoring systems, and transmission terminals, dominated the submarine communication market component segment in 2024. This growth stems from increasing adoption to enhance network reliability, simplify maintenance, and reduce operational costs.

8.2 Advanced PFE Technology Developments

Recent technological advances in power feeding equipment include:

Voltage Capability Enhancement: Modern PFE systems now achieve maximum output voltages up to 18 kV, with industry leaders pushing development beyond this threshold. This increased voltage capability enables:

- Longer cable segments without intermediate power feed points

- Single-end feeding capability for transpacific systems in fault conditions

- Support for increased repeater power requirements in high-capacity DWDM systems

Portable PFE Solutions: New portable high voltage PFE systems (PFE-P) facilitate cable repair operations and temporary installations. These compact, mobile units provide:connection flexibility during maintenance, rapid deployment for emergency repairs, and reduced logistical requirements for cable ship operations.

Shipborne PFE Systems: Advanced 6 kV to 20 kV systems installed on major cable laying ships have become the preferred choice of cable shipbuilders and owners. These systems enable:

- Real-time power feeding during cable laying operations

- Immediate fault detection and localization

- System testing and commissioning at sea

8.3 Recent Major Submarine Cable Projects

Several significant projects highlight the ongoing expansion of submarine cable infrastructure:

- Kochi-Lakshadweep Islands System (2024): Completed by a leading vendor in collaboration with Indian authorities, this 1,870 km system connects 11 remote islands, demonstrating power feeding systems' role in digital inclusion initiatives

- Microsoft Subsea Cable Projects (2025): Three new cables (Tuskar, SOBR1, SOBR2) connecting Ireland to Wales for enhanced data center connectivity, showcasing enterprise investment in dedicated infrastructure

- Google Pacific Investment (2024): $1 billion allocation for new subsea cable networks between United States and Japan, emphasizing content provider infrastructure investments

8.4 Environmental Considerations

Modern power feeding system design increasingly considers environmental factors:

Electromagnetic Induction: Submarine cables near high-voltage AC power transmission lines or within electric railway catchment areas may experience induced voltages. Design considerations include:

- Assessment of potential induction sources during route planning

- Inclusion of surge protection devices in terminal equipment

- Coordination with power utilities for mitigation measures

Lightning Protection: Terminal stations near coastal areas face lightning strike risks. Modern PFE designs incorporate:

- Multi-stage surge protection circuits

- Effective grounding systems with low resistance paths

- Isolation transformers and optical coupling for critical circuits

8.5 Future Technology Directions

Emerging trends shaping the future of power feeding systems include:

Smart Monitoring and Control: Integration of advanced sensors and AI-based analytics for predictive maintenance, real-time optimization, and automated fault response.

Higher Efficiency Converters: Wide bandgap semiconductor adoption (SiC, GaN) enabling higher switching frequencies, reduced losses, and more compact designs.

Hybrid Power Systems: Development of systems supporting both constant current and constant voltage modes for multi-purpose cable applications including telecommunications and power transmission.

Standardization Initiatives: Ongoing work in ITU-T and IEEE to establish comprehensive standards for next-generation power feeding systems supporting terabit-scale transmission.

9. Best Practices & Practical Guidelines

Successful power feeding system implementation requires careful attention to design principles, installation procedures, and operational practices developed through decades of industry experience.

9.1 Design Phase Best Practices

Comprehensive Power Budget Development:

- Account for all voltage drops including PFE impedance, cable resistance (temperature-adjusted), repeater drops, land cables, earth cables, and earth potential difference

- Include adequate repair margin (typically 10-20%) for future cable/repeater additions

- Consider worst-case scenarios including maximum EPD and temperature variations

- Verify all power feeding paths support single-end feeding capability where economically feasible

Component Withstand Voltage Verification:

- Ensure maximum system voltage never exceeds lowest component withstand voltage

- Apply Weibull statistics for dielectric breakdown risk assessment

- Include safety margins beyond calculated maximum voltages

- Consider aging effects on insulation materials over 25-year lifetime

Earth Electrode Design:

- Target earth ground resistance below 3Ω for optimal performance

- Use multiple ground electrodes or mesh networks for redundancy

- Conduct thorough soil resistivity surveys before installation

- Implement proper earth electrode sizing to support maximum expected currents

- Consider electrode material selection for corrosion resistance in marine environments

9.2 Installation and Commissioning Guidelines

Pre-Installation Testing:

- Verify PFE output characteristics match design specifications

- Confirm all redundancy mechanisms function correctly

- Test emergency shutdown and discharge systems

- Validate current and voltage detection accuracy

Commissioning Sequence:

- Measure earth ground resistance and compare to design values

- Perform capacitance measurements on complete cable system

- Conduct low-current power-up to verify repeater operation

- Gradually increase to nominal operating current with continuous monitoring

- Measure and record actual EPD for future reference

- Test BU switching sequences if applicable

- Verify electroding function and signal detection range

9.3 Operational Best Practices

Routine Monitoring:

- Continuously monitor output voltage and current for deviations

- Track earth potential difference variations, especially during geomagnetic activity

- Log all power feeding path reconfigurations

- Maintain detailed records of PFE voltage adjustments

Preventive Maintenance:

- Schedule regular PFE component inspections and testing

- Periodically verify redundant equipment through controlled switching

- Test backup power supplies and automatic transfer switches

- Inspect and maintain earth electrode connections

- Update master voltage/current reference tables after repairs

9.4 Fault Response Procedures

Fault Response Flowchart

Step-by-step procedure for handling cable faults

9.5 Safety Protocols

Power feeding systems operate at dangerous high voltages requiring strict safety procedures:

Personnel Protection:

- Enforce lockout/tagout procedures before any PFE maintenance

- Utilize automatic shutdown systems when accessing high-voltage terminals

- Maintain proper isolation distances from energized equipment

- Require appropriate personal protective equipment for all operations

- Provide comprehensive training on high-voltage hazards

Earth Protection:

- Monitor earth electrode integrity continuously

- Implement automatic earth switching on degradation detection

- Limit voltage differential between system earth and station earth to <20V normal, <90V exceptional

- Verify earth connections before energizing system

Discharge Procedures:

- Always discharge cable capacitance before maintenance

- Use controlled discharge through resistive circuits first

- Verify zero voltage with appropriate test equipment

- Apply grounding before touching conductors

Technical Specifications (Current Systems):

- Maximum PFE voltage: 18 kV (modern systems), development beyond this threshold ongoing

- Operating current: 1.0A ±0.3A for optical amplifiers (reduced from 1.6A in 3R systems)

- Current distribution in repeater: 80% laser diodes, 10% control circuits, 10% electroding margin

- Earth potential difference: ~0.1 V/km nominal, up to 0.3 V/km per ITU-T G.977

- Design lifetime: 25+ years with proper maintenance

- System reliability: 99.999% (five nines) availability

- Electroding capability: ±80 mA in-service, ±160 mA out-of-service, >500 km detection range

- Surge protection: >200A long pulse, 450A/15kV short pulse capability in modern PFEs

Safety Principles (Why It's Safe for Marine Life):

- Current confined to insulated conductor – zero current leakage to seawater under normal operation

- Multiple redundant insulation layers exceed voltage requirements by 1.5-2× safety factor

- Marine life completely safe – 50+ years operational history with zero documented harm

- Ocean water NOT in current path – cable acts as direct wire, earth provides distant return

- Constant current design limits energy even in fault conditions (1.0A total system current)

- Cable outer surface at seawater potential – no voltage difference to surrounding environment

- Earth return current density negligible – 1.0A spreads over enormous geological cross-section

- Automatic shutdown systems protect personnel from high voltage exposure

Key Takeaways

Power feeding systems are essential infrastructure enabling global submarine cable networks that carry 99% of international data traffic. Understanding their design, operation, and maintenance is crucial for modern telecommunications.

Critical Success Factors:

- Constant current feeding (1.0A ±0.3A) ensures stable repeater operation regardless of system length

- Double-end feeding with master-master control provides automatic fault tolerance

- Current flows ONLY inside insulated conductor – multiple polyethylene and steel armor layers prevent any leakage to seawater

- Earth return path uses deep geological layers – NOT ocean water along cable route

- N:1 power converter and M:N control redundancy in PFE ensures exceptional reliability (99.999%)

- Earth electrode resistance target: <3Ω critical for proper system grounding

- Comprehensive power budget includes PFE impedance, cable drops, repeaters, earth components, EPD (~0.1 V/km), and repair margins

- Branch PFE polarity MUST be negative to prevent sea earth electrode elution (1A positive for 1 year = 21 kg copper loss)

- Automatic fault detection and voltage adjustment maintain operation even during shunt faults

- ITU-T G.977 compliance and adherence to international standards mandatory

For educational purposes in optical networking and DWDM systems

Note: This guide is based on industry standards, best practices, and real-world implementation experiences. Specific implementations may vary based on equipment vendors, network topology, and regulatory requirements. Always consult with qualified network engineers and follow vendor documentation for actual deployments.

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here