3 min read

Optical Modulation and Constellation Diagrams: A Comprehensive Engineering Guide

Understanding the Foundation of Modern High-Capacity Coherent Optical Communications

Introduction

Optical modulation techniques represent the fundamental mechanism through which digital information is encoded onto light waves for transmission through fiber optic networks. The constellation diagram, a graphical representation showing all possible symbol states in the complex signal space, has emerged as both a powerful design tool and an essential diagnostic instrument in modern optical communications. Understanding these concepts is no longer optional for engineers working with today's high-speed networks carrying terabits of data across metropolitan areas, continental backbones, and undersea cables connecting the world.

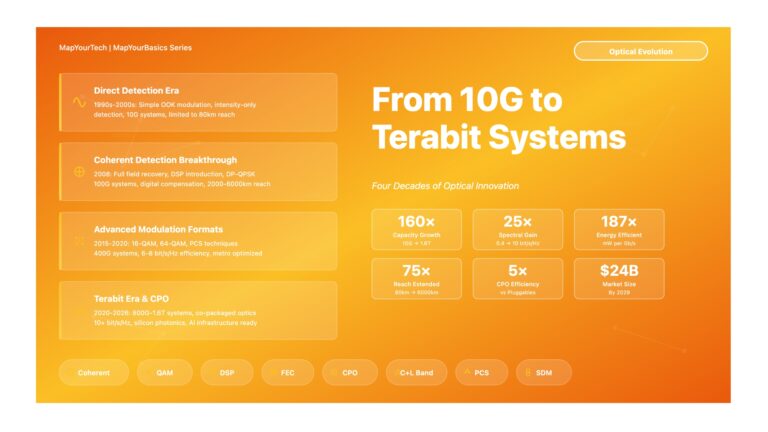

The journey from simple intensity modulation to sophisticated multi-dimensional signaling schemes mirrors the exponential growth in network capacity demands. Early optical systems used straightforward on-off keying where the presence or absence of light represented binary ones and zeros. Modern coherent systems exploit the full electromagnetic nature of light, modulating amplitude, phase, and polarization simultaneously to achieve spectral efficiencies that seemed impossible just two decades ago. This evolution has been enabled by advances in both optical components and digital signal processing that allow us to manipulate and detect the optical field with extraordinary precision.

This comprehensive guide explores the entire spectrum of optical modulation formats from foundational concepts through cutting-edge techniques. We examine how constellation diagrams capture the essential properties of each format, revealing the fundamental trade-offs between spectral efficiency, power efficiency, and robustness against impairments. Whether you are designing next-generation transceivers, planning network capacity upgrades, or developing signal processing algorithms, the principles presented here form the theoretical foundation that connects physics, information theory, and practical engineering.

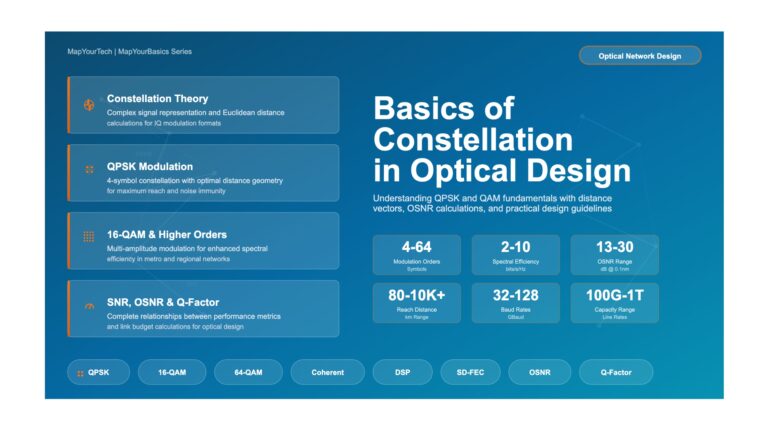

Figure: Comprehensive overview showing constellation density evolution and performance trade-offs across modulation orders. Note how symbol spacing decreases exponentially while OSNR requirements increase linearly with each step in format complexity.

1. Fundamentals of Signal Space and Constellation Representation

1.1 The Complex Signal Space

In coherent optical communications, we represent transmitted signals as complex numbers where the real part corresponds to the in-phase component and the imaginary part represents the quadrature component of the optical field. This mathematical abstraction allows us to work with phase and amplitude information simultaneously, treating the two-dimensional signal space as a unified entity. The constellation diagram visualizes this space by plotting each possible transmitted symbol as a point in the complex plane.

The geometric properties of constellation arrangements directly determine system performance characteristics. The minimum Euclidean distance between constellation points governs noise tolerance, while the average symbol energy determines required transmit power. The arrangement of points in the signal space reflects deliberate design choices balancing these competing requirements. A well-designed constellation maximizes the spacing between symbols subject to constraints on average power, peak power, and implementation complexity.

For a modulation format with M symbols, we can transmit log2(M) bits per symbol, defining the spectral efficiency. However, increasing M necessarily reduces the spacing between points if we maintain constant average power. This fundamental trade-off between spectral efficiency and power efficiency pervades all aspects of modulation format design. Understanding this relationship through the lens of constellation geometry provides intuition that guides practical system optimization.

Key Performance Metrics Derived from Constellations

Several critical parameters emerge directly from constellation geometry. The average symbol energy Es represents the mean squared distance of constellation points from the origin, directly relating to transmit power requirements. The minimum Euclidean distance dmin between any two points determines the noise margin, with larger distances providing better error performance. The constellation figure of merit combines these factors, quantifying the power efficiency relative to other formats at the same spectral efficiency. These metrics allow rigorous comparison of competing modulation schemes and guide selection for specific applications.

1.2 Bit-to-Symbol Mapping and Gray Coding

The mapping between binary bit patterns and constellation points significantly impacts bit error rate performance. In Gray coding, adjacent constellation points differ by only a single bit, ensuring that the most probable symbol errors (those involving confusion between neighboring points) cause only single bit errors rather than multiple bit errors. This property effectively halves the bit error rate compared to natural binary coding for many practical scenarios where errors predominantly involve adjacent symbols.

For higher-order modulation formats, maintaining Gray coding across all nearest neighbors becomes impossible, requiring careful optimization of the bit labeling. The selected mapping interacts with soft-decision forward error correction decoders, affecting the achievable generalized mutual information. Modern transceivers may adaptively adjust bit-to-symbol mappings based on observed channel conditions to maximize effective throughput given the deployed FEC code.

2. Intensity Modulation Formats

2.1 On-Off Keying Fundamentals

On-Off Keying represents the most straightforward optical modulation scheme where binary data directly controls laser output intensity. In the ON state corresponding to binary one, the laser emits at full power A, while the OFF state for binary zero produces zero or minimal output. The extreme simplicity of this approach enables low-cost implementations using directly modulated lasers and simple photodetection without requiring complex coherent receivers or digital signal processing.

The OOK constellation consists of only two points along the real axis at amplitudes 0 and A. This one-dimensional signaling achieves a spectral efficiency of one bit per symbol. While the large spacing between symbols (distance equals A) provides reasonable noise tolerance, OOK suffers significant limitations including sensitivity to chromatic dispersion and inability to use phase information. These constraints restrict OOK to relatively short distances or require dispersion compensation that adds system complexity and cost.

Modern systems have largely superseded basic OOK with more sophisticated intensity modulation schemes for anything beyond short-reach applications. However, OOK variants including return-to-zero and differential encoding remain important in specific niches. The format serves primarily in cost-sensitive deployments where transmission distances stay below 10 kilometers and data rates remain moderate. Access networks and short data center links represent the primary application domain where OOK simplicity outweighs its performance limitations.

2.2 Pulse Amplitude Modulation Extensions

Pulse Amplitude Modulation generalizes OOK by using multiple discrete amplitude levels rather than just two states. In 4-PAM, four intensity levels encode two bits per symbol, doubling spectral efficiency compared to OOK. The constellation points lie along the real axis at amplitudes -3A, -A, +A, and +3A for a standard Gray-coded implementation. This achieves the same 2 bits per symbol as QPSK but using only amplitude modulation rather than phase modulation.

The mathematical description of M-PAM signals follows directly from the discrete amplitude representation. Each symbol takes value sk equal to (2k - 1 - M) times the unit amplitude A, where k ranges from 1 to M. The average symbol energy works out to (M squared minus 1) times A squared divided by 3. As M increases, achieving the same total energy requires reducing A, which shrinks the minimum distance between levels. This makes higher-order PAM increasingly sensitive to noise and limits practical implementations to 4-PAM or occasionally 8-PAM.

PAM finds primary application in short-reach optical interconnects where simplicity and direct detection remain valued. The format has gained renewed interest for 100 Gigabit Ethernet implementations using four parallel 25 Gbaud PAM-4 lanes. However, the inherent inefficiency compared to two-dimensional modulation formats restricts PAM to scenarios where phase modulation proves impractical or where legacy compatibility drives design choices. For most modern coherent systems, PAM serves mainly as a conceptual stepping stone toward understanding QAM rather than as a deployed format.

3. Phase Shift Keying Modulation Families

3.1 Binary Phase Shift Keying Properties

Binary Phase Shift Keying encodes information by shifting the carrier phase between two states separated by 180 degrees. Unlike intensity modulation, BPSK maintains constant optical power while conveying information through phase changes. This constant-envelope property provides excellent tolerance to fiber nonlinear effects that plague amplitude-varying formats. The two constellation points sit at opposite sides of a circle in the complex plane, typically at phases 0 and π radians.

The signal representation for BPSK takes the form A cosine of (2π times carrier frequency times time plus φk) where the phase φk equals either 0 or π depending on the transmitted bit. Both symbols have identical energy equal to A squared, giving average symbol energy Es equal to A squared. The Euclidean distance between the two antipodal points reaches 2A, the maximum possible for any two-point constellation with this energy. This optimal geometry translates to approximately 3 decibels better sensitivity compared to OOK at equivalent average power.

BPSK requires coherent detection with carrier recovery to demodulate the phase-encoded signal. This added complexity limits its direct application in optical systems where polarization-multiplexed variants achieve better spectral efficiency. However, BPSK forms the building block for more sophisticated formats including QPSK and set-partitioned modulation schemes. Understanding BPSK behavior provides essential foundation for analyzing these higher-order phase modulation formats that dominate modern coherent optical networks.

3.2 Quadrature Phase Shift Keying Architecture

Quadrature Phase Shift Keying extends the phase modulation concept to four states, encoding two bits per symbol while maintaining the constant-envelope advantage. The four constellation points arrange symmetrically at phases π/4, 3π/4, -3π/4, and -π/4, forming a square in the complex plane. When using Gray coding, adjacent points differ by only one bit, optimizing performance with practical forward error correction codes. This symmetric arrangement provides equal noise margin in all directions, simplifying receiver design and analysis.

The mathematical formulation decomposes a QPSK signal into in-phase and quadrature components, each carrying independent bit streams. We can write the modulated signal as I(t) times cosine of 2π carrier frequency plus Q(t) times sine of 2π carrier frequency, where I(t) and Q(t) each take values plus or minus A divided by root 2. This orthogonal representation allows treating QPSK as two independent BPSK signals on carriers separated by 90 degrees, simplifying both transmitter and receiver implementation using IQ modulators and mixers.

QPSK has become the dominant modulation format for long-haul coherent optical transmission. The spectral efficiency of 2 bits per symbol balances capacity and robustness effectively. When combined with polarization-division multiplexing to create dual-polarization QPSK, the overall rate reaches 4 bits per symbol while maintaining excellent noise tolerance and nonlinearity resistance. Commercial 100 Gigabit and 200 Gigabit coherent systems almost universally employ DP-QPSK as the baseline format, testifying to its optimal balance of performance, complexity, and reliability.

QPSK Performance Analysis

Symbol Energy (all symbols equal):

Es = A²

Bit Energy:

Eb = Es / 2 = A² / 2

Minimum Euclidean Distance:

dmin = |s1 - s2| (between adjacent points)

= |(A/√2 + jA/√2) - (-A/√2 + jA/√2)|

= A√2

Symbol Error Probability (AWGN):

Ps ≈ 2Q(√[2Es/N0]) - Q²(√[2Es/N0])

Bit Error Probability (with Gray coding):

Pb ≈ Q(√[2Eb/N0])

Where Q(x) is the complementary error function:

Q(x) = (1/√2π) · ∫x∞ exp(-t²/2) dt

Required OSNR for BER = 10-3:

OSNR ≈ 11-13 dB (in 0.1 nm bandwidth)3.3 Higher-Order PSK Limitations

Extending phase modulation beyond QPSK faces fundamental geometric constraints that limit practical deployment. Eight-PSK uses eight equally spaced phase states at 45-degree intervals, achieving 3 bits per symbol. However, the angular spacing shrinks from 90 degrees in QPSK to just 45 degrees, significantly reducing the Euclidean distance between adjacent points. For constant average power, the 8-PSK minimum distance is only 0.77 times that of QPSK, requiring substantially higher signal-to-noise ratio for equivalent error performance.

The minimum distance for M-PSK decreases as twice the amplitude times the sine of (π divided by M). As M grows large, this distance approaches 2πA divided by M, shrinking linearly with increasing constellation size. Meanwhile, spectral efficiency grows only logarithmically as log base 2 of M. This unfavorable scaling means each doubling of M requires approximately 6 decibels more OSNR while adding only one additional bit per symbol. Beyond 8-PSK, the required OSNR increases become impractical for most optical communication scenarios.

These limitations motivated development of quadrature amplitude modulation formats that exploit both amplitude and phase dimensions. By allowing variable amplitude in addition to phase shifts, QAM achieves better distance properties than high-order PSK at equivalent spectral efficiencies. Consequently, pure PSK formats beyond QPSK see limited deployment in optical networks. The exception involves specialized applications like satellite communications where constant-envelope properties outweigh the OSNR penalty. For terrestrial and subsea optical systems, the industry has converged on QAM for applications requiring more than 2 bits per symbol per polarization.

4. Quadrature Amplitude Modulation Theory and Practice

4.1 QAM Constellation Construction

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation achieves high spectral efficiency by varying both the amplitude and phase of the carrier signal. The most common QAM constellations arrange symbols in a square grid pattern in the complex plane, with points equally spaced along both the in-phase and quadrature axes. This regular structure simplifies both generation and detection while providing good geometric properties. Square M-QAM where M equals 4m (16-QAM, 64-QAM, 256-QAM) dominate practical implementations due to their straightforward mapping to independent PAM signals on I and Q axes.

We can mathematically describe square QAM as the Cartesian product of two root-M PAM constellations. The in-phase component I takes values from the set negative (√M minus 1) times A through positive (√M minus 1) times A in steps of 2A, and similarly for the quadrature component Q. Each of the M combinations of I and Q values represents one constellation point encoding log2(M) bits. For 16-QAM, both I and Q use 4-PAM levels (-3A, -A, +A, +3A), creating a 4-by-4 grid with 16 total symbols encoding 4 bits each.

The average symbol energy for square M-QAM equals (M minus 1) times A squared divided by 3. The minimum distance between adjacent points equals 2A, independent of M. However, maintaining fixed average power as M increases requires reducing A, which shrinks the absolute minimum distance. This scaling explains why higher-order QAM formats demand progressively higher OSNR. Each quadrupling of M (adding 2 bits per symbol) approximately doubles the number of amplitude levels on each axis, reducing minimum distance by half and requiring roughly 6 decibels additional OSNR.

4.2 16-QAM Implementation and Performance

16-QAM represents the first step beyond QPSK in spectral efficiency for square QAM constellations, doubling the bit count to 4 bits per symbol. The constellation forms a 4-by-4 square grid with three distinct symbol amplitudes. The inner four points have lowest energy, the outer four corners have highest energy, and the eight edge points occupy intermediate energy levels. This amplitude variation introduces sensitivity to nonlinear impairments that constant-envelope QPSK avoids, fundamentally limiting transmission distance even at adequate OSNR.

Comparing 16-QAM to QPSK at constant average symbol energy reveals the performance trade-off. The 16-QAM minimum distance is only two-thirds that of QPSK (2A/3 versus A√2 when normalized to equal energy). This 3.5 decibel reduction in noise margin translates to approximately 6 decibels higher required OSNR in practice after accounting for decision region geometries. However, 16-QAM delivers twice the spectral efficiency, allowing systems to achieve higher capacity over the same bandwidth or equivalently to reduce symbol rate and relax electrical component requirements.

Practical 16-QAM systems find their niche in metro and regional networks where distances stay below 500 kilometers. The format enables 200 Gigabit and 400 Gigabit transmission at symbol rates around 32 to 64 Gbaud. Polarization-multiplexed 16-QAM achieves 8 bits per symbol (4 bits per polarization), delivering excellent spectral efficiency for applications where fiber count or wavelength count constraints drive economics. The key requirement involves sufficient amplifier OSNR (typically 17 to 20 decibels) and moderate fiber nonlinearity through controlled launch powers or dispersion management.

4.3 64-QAM and Higher Orders

64-QAM pushes spectral efficiency to 6 bits per symbol using an 8-by-8 grid arrangement with 64 total constellation points. The format supports very high capacity over relatively short distances, targeting data center interconnect and metro core applications. Each axis uses 8-PAM signaling with amplitude levels from negative 7A through positive 7A in steps of 2A. The resulting constellation exhibits substantial amplitude variation with peak-to-average power ratio approaching 3.7 times in voltage or about 5.7 decibels in power.

The geometric properties of 64-QAM make clear the scaling challenges. With 64 points in the same average energy constellation as 16-QAM, the minimum distance shrinks to approximately 2A/7, roughly one-third of 16-QAM. This translates to 9.5 decibels less noise margin, demanding OSNR values typically exceeding 24 decibels at the receiver. Additionally, the large amplitude variation causes severe self-phase modulation at fiber launch powers that work well for QPSK. Practical 64-QAM systems must operate at reduced powers (often 6 to 8 decibels below QPSK optimal), further limiting reach through accumulated noise.

Despite these challenges, 64-QAM enables extraordinary capacities for short-distance transmission. Dual-polarization 64-QAM delivers 12 bits per symbol, supporting 800 Gigabit and even 1.2 Terabit per wavelength at achievable symbol rates. The format has found commercial success in data center interconnect links spanning up to 80 kilometers where fiber quality is high and inline amplification provides ample OSNR. Experimental systems have demonstrated 256-QAM and even 1024-QAM, though these ultra-high-order formats remain limited to sub-kilometer links and laboratory demonstrations due to their extreme sensitivity to all forms of impairment.

Nonlinearity and Peak-to-Average Power Ratio Challenges

Higher-order QAM formats suffer disproportionately from fiber Kerr nonlinearity due to their amplitude variation. The refractive index change induced by the Kerr effect depends on instantaneous optical power, causing high-amplitude symbols to experience larger nonlinear phase shifts than low-amplitude symbols. This amplitude-dependent phase rotation distorts the constellation, moving points away from their intended locations in a systematic pattern that degrades performance even with perfect OSNR. The peak-to-average power ratio exacerbates this effect, as outer constellation points carry significantly more power than inner points. Reducing launch power mitigates nonlinearity but increases accumulated ASE noise, creating a narrow optimal power window. For 64-QAM and above, this window becomes so restricted that even slight variations in fiber loss or splice quality can push the system outside acceptable operating conditions.

6. Optical Signal Quality Visualization: Constellation and Eye Diagrams

While the interactive modulation calculator above demonstrates how system parameters determine theoretical capacity, optical engineers need additional diagnostic tools to assess actual signal quality in deployed systems. Two visualization techniques form the cornerstone of coherent optical receiver performance analysis: constellation diagrams and eye diagrams. These complementary views reveal signal degradation mechanisms invisible in simple power measurements and provide actionable insight into specific impairment sources.

The constellation diagram plots received signal samples in the complex I-Q plane, directly visualizing how cleanly the receiver can distinguish between different transmitted symbols. In an ideal noiseless system, all samples cluster precisely at their intended constellation points. Real systems exhibit spreading around these ideal locations due to amplified spontaneous emission noise, phase noise from laser linewidth, nonlinear effects, and chromatic dispersion residuals. The pattern of constellation spreading reveals the dominant impairment type, enabling targeted mitigation strategies.

The eye diagram complements this frequency-domain view by overlaying many symbol periods in the time domain, creating a pattern that resembles an open eye when signal quality is good. The vertical height of the eye opening indicates amplitude discrimination margin, while the horizontal width shows timing tolerance. A wide-open eye with thin transition edges indicates excellent signal quality suitable for long-distance transmission. As the eye closes vertically, amplitude noise is degrading performance. As the eye narrows horizontally or transitions spread, timing jitter becomes problematic. Engineers use eye diagram measurements to evaluate equalizer performance, adjust decision threshold levels, and diagnose issues with timing recovery circuits.

Signal Quality Diagnostic Tool

Explore how modulation format, OSNR, phase noise, and symbol rate affect constellation and eye diagrams in real-time

Constellation Diagram (I-Q Plane)

Eye Diagram (Time Domain)

Understanding the Visualizations

Constellation Diagram: Shows signal decision points in the complex I-Q plane. Each dot represents a possible symbol state. Tighter clustering indicates cleaner signal with less noise.

Eye Diagram: Overlays multiple symbol transitions in time domain. A wide-open eye indicates good signal quality with clear timing margins and voltage levels. Eye closure shows signal degradation.

Interpreting Signal Quality Visualizations

The visualization tool above demonstrates how multiple impairment mechanisms combine to degrade optical signal quality in real transmission systems. When you select QPSK modulation with thirty decibels OSNR and zero phase noise, you observe four tight constellation clusters positioned at the ideal quadrature phase shift keying locations and a wide-open eye diagram with approximately ninety-five percent vertical opening. This represents the baseline reference condition that system designers target for deployed networks operating well above their forward error correction threshold.

Reducing OSNR from thirty to fifteen decibels reveals the progressive impact of amplified spontaneous emission noise accumulated through multiple optical amplifier stages. The constellation points spread radially outward from their ideal positions as Gaussian noise adds random perturbations to both in-phase and quadrature signal components. Simultaneously, the eye diagram traces thicken vertically, reducing the amplitude margin between logic levels. At fifteen decibels OSNR with QPSK modulation, the system operates near its forward error correction limit, with minimal margin remaining for additional impairments like chromatic dispersion residuals or nonlinear phase noise.

Phase noise, introduced through the phase noise slider, demonstrates a fundamentally different degradation mechanism arising from finite laser linewidth. As you increase phase noise from zero to ten degrees, the constellation points transform from tight clusters into circular arcs or complete rings. This circular spreading occurs because phase noise causes the received signal's phase to wander randomly around the intended constellation point. The eye diagram simultaneously develops horizontal spreading at the crossing points where signal transitions occur between amplitude levels. This timing jitter directly reduces the available window for symbol sampling, forcing the receiver's clock recovery circuit to maintain tighter timing tolerances.

The modulation format presets reveal the fundamental trade-off between spectral efficiency and noise tolerance that drives optical transport network design decisions. When you switch from QPSK to sixteen-level quadrature amplitude modulation, the number of constellation points quadruples from four to sixteen, doubling the bits encoded per symbol from two to four. However, this doubling of spectral efficiency comes at a cost: the minimum Euclidean distance between adjacent constellation points decreases by a factor of approximately three, reducing the noise margin by half in voltage terms or six decibels in power terms. The eye diagram clearly visualizes this reduced margin, showing multiple stacked amplitude levels with smaller vertical spacing between them.

The probabilistic constellation shaping preset demonstrates an advanced technique that optimizes the trade-off between capacity and reach by assigning non-uniform transmission probabilities to different constellation points. When you select MPCS modulation, the constellation diagram shows variable-sized clusters with inner points appearing as large, dense groups while outer high-amplitude points show fewer scattered samples. This probability distribution concentrates transmitted energy near the constellation center where symbols require less optical power and tolerate noise better, while using high-amplitude outer points sparingly only when necessary for data encoding. The eye diagram for probabilistic constellation shaping typically shows cleaner, less noisy amplitude levels compared to uniform sixty-four-level quadrature amplitude modulation at the same average optical signal-to-noise ratio, reflecting the two to three decibel shaping gain this technique achieves in deployed systems.

5. Multi-Dimensional and Advanced Modulation Formats

5.1 Polarization-Division Multiplexing Principles

Polarization-division multiplexing exploits the two orthogonal polarization states of light as independent communication channels, effectively doubling capacity without requiring additional optical spectrum. In a PDM system, separate data streams modulate the horizontal (X) and vertical (Y) polarization components using the same modulation format. For instance, PDM-QPSK combines two independent QPSK signals on orthogonal polarizations, creating a four-dimensional signal space with 16 possible states encoding 4 bits per symbol.

The mathematical description of PDM signals requires four-dimensional vectors where components represent IX, QX, IY, and QY. Each transmitted symbol occupies a specific location in this 4D space. While we cannot directly visualize four dimensions, we can project the signal onto 2D planes showing each polarization separately. The key advantage emerges from simultaneously transmitting on both polarizations, doubling spectral efficiency compared to single-polarization transmission at the same per-polarization modulation order.

PDM introduces new technical challenges absent in single-polarization systems. Polarization mode dispersion in the fiber causes the two polarization states to travel at slightly different velocities and potentially couple energy between polarizations. Additionally, fiber birefringence randomly rotates the polarization orientation along the transmission path, scrambling the X and Y components. Modern coherent receivers employ multiple-input multiple-output digital signal processing with adaptive equalizers to separate the polarization-multiplexed signals. The 2-by-2 butterfly structure has become standard, using finite impulse response filters that automatically track and compensate polarization transformations without requiring manual alignment.

5.2 Set-Partitioned Modulation Optimization

Set-partitioned QAM formats optimize four-dimensional constellation geometry to improve power efficiency beyond what independent modulation of each polarization achieves. The key insight involves carefully selecting which combinations of X-polarization and Y-polarization symbols are allowed, maximizing the minimum Euclidean distance in 4D space for a given average energy. This geometric optimization can provide shaping gains of 1 to 2 decibels compared to conventional square QAM, extending reach or enabling higher order modulation.

The most prominent example is 128-SP-QAM, which achieves 7 bits per symbol (3.5 bits per dimension) using Ungerboeck set partitioning principles. Starting with the 16 points of DP-QPSK, the constellation recursively partitions the signal space while maintaining maximum spacing. A single parity bit enforces dependencies between the two polarizations, creating the optimal 128-point arrangement. The mathematical structure involves the D4 lattice, a well-studied geometric object providing excellent sphere-packing properties in four dimensions.

Experimental demonstrations have shown 128-SP-QAM and 512-SP-QAM achieving 1 to 1.5 decibel gains compared to their square QAM counterparts at equivalent spectral efficiency. However, implementation complexity and the irregular constellation shape complicate practical deployment. The bit-to-symbol mapping becomes more complex, carrier recovery algorithms must account for asymmetric symbol arrangements, and laser phase noise affects different symbols unequally. These practical considerations have limited commercial adoption despite the attractive theoretical gains, with most deployed systems preferring the simplicity of square QAM even at modest efficiency loss.

5.3 Probabilistic Constellation Shaping Revolution

Figure: Probabilistic Constellation Shaping (PCS) concept showing the transformation from uniform symbol probability (left) to Gaussian-like shaped distribution (right). Circle size represents transmission probability - larger circles for frequently transmitted low-amplitude symbols, smaller circles for rarely transmitted high-amplitude symbols. The process flow and benefits demonstrate how PCS approaches Shannon limit performance.

Probabilistic constellation shaping represents a paradigm shift in how we design and operate modulation systems. Rather than transmitting all constellation points with equal probability, PCS biases the symbol distribution toward lower-amplitude points that require less energy. This creates a Gaussian-like amplitude distribution that approaches the capacity-achieving input distribution for additive white Gaussian noise channels. The technique enables systems to approach Shannon limit performance more closely than uniform distributions allow.

The theoretical foundation rests on information theory showing that Gaussian-distributed signals maximize channel capacity for power-limited AWGN channels. While discrete QAM cannot create truly Gaussian distributions, probabilistic shaping approximates this ideal by making high-amplitude outer symbols rare and low-amplitude inner symbols frequent. The shaping gain reaches its maximum value of about 1.53 decibels (difference between uniform and Gaussian capacity) as constellation size grows large. Practical systems with 64-QAM or 256-QAM can capture 0.8 to 1.2 decibels of this potential gain.

Implementation requires a distribution matcher at the transmitter that converts uniformly distributed information bits into symbols following the desired probability distribution. Several algorithms exist including constant composition distribution matching based on arithmetic coding and enumerative sphere shaping. At the receiver, the inverse operation recovers uniform bits from shaped symbols. The combination of geometric shaping (optimizing point locations) and probabilistic shaping (optimizing transmission probabilities) represents current state-of-the-art, with commercial transceivers using PCS to enable adaptive rate control from 400 to 800 Gigabits per second using the same modulation hardware.

6. Performance Evaluation and Diagnostic Metrics

6.1 Error Vector Magnitude Analysis

Error Vector Magnitude quantifies constellation quality by measuring the deviation between received symbols and their ideal locations in the complex plane. For each received symbol, we calculate the error vector as the complex difference between the measured location and the intended constellation point. EVM is expressed as the root-mean-square of these error vectors normalized by the constellation average power, typically presented as a percentage or in decibels.

The mathematical calculation first identifies the nearest constellation point to each received symbol, then computes the error vector magnitude. Summing the squared magnitudes across all measured symbols and dividing by the number of symbols gives the mean squared error. Taking the square root and normalizing by average symbol power yields the RMS EVM. Converting to decibels as 20 times log base 10 of the RMS value provides the standard reporting format. Typical specifications require EVM below negative 18 decibels for QPSK, below negative 24 decibels for 16-QAM, and below negative 30 decibels for 64-QAM.

EVM captures the cumulative impact of all impairments including transmitter DAC quantization, IQ modulator imbalance, laser phase noise, amplifier distortion, fiber chromatic dispersion residuals, and receiver ADC noise. Unlike simple bit error rate measurements that only indicate success or failure of demodulation, EVM provides diagnostic information about impairment severity and sources. A constellation with radial error patterns indicates phase noise dominance, while tangential spreading suggests amplitude noise. Asymmetric patterns reveal IQ imbalance or skew between I and Q paths. This diagnostic capability makes EVM essential for transceiver development and manufacturing test.

6.2 Generalized Mutual Information

Generalized Mutual Information has emerged as the preferred metric for evaluating coded modulation performance in systems using practical forward error correction. Unlike Shannon capacity calculations that assume optimal maximum likelihood decoding, GMI accounts for the bit-metric decoding employed by modern iterative FEC codes including LDPC and turbo codes. For a given modulation format, channel SNR, and bit-to-symbol mapping, GMI predicts the maximum FEC code rate that can achieve arbitrarily low error rates.

The GMI calculation considers the mutual information between transmitted bits and the soft bit metrics produced by the demodulator. Unlike standard mutual information between transmitted and received symbols, GMI captures the degradation caused by bit-wise detection rather than symbol-wise detection. Gray-coded square QAM constellations typically achieve GMI within 0.1 to 0.3 bits per symbol of the uncoded mutual information. Non-Gray mappings or irregular constellation shapes may exhibit larger gaps, reducing effective throughput.

The achievable information rate multiplies GMI by the symbol rate to give the maximum user data rate supportable by the FEC-coded system. This metric directly indicates system capacity accounting for both modulation and coding. Network operators use AIR to characterize link margins and plan capacity. A system designed for 400 Gigabit operation with 7% FEC overhead requires AIR of 430 Gigabits per second. Measuring actual GMI at various OSNR values reveals how much margin exists and whether adaptive coding or modulation adjustments could increase throughput.

6.3 OSNR Requirements Across Formats

The required optical signal-to-noise ratio fundamentally determines which modulation formats work for specific applications. OSNR measured in a 0.1 nanometer reference bandwidth represents the ratio of signal power to amplified spontaneous emission noise power. Each increase in modulation order demands approximately 6 to 7 decibels additional OSNR to maintain the same pre-FEC bit error rate, creating the fundamental capacity-reach trade-off.

For dual-polarization coherent systems, DP-BPSK achieves error rates below threshold with OSNR around 8 to 10 decibels, enabling maximum reach in submarine and ultra-long-haul applications. DP-QPSK requires 11 to 13 decibels, still providing excellent noise margin for links spanning thousands of kilometers. DP-8QAM and DP-16QAM need 15 to 17 and 17 to 20 decibels respectively, limiting them to metro and regional distances. DP-32QAM and DP-64QAM demand 21 to 24 and 24 to 28 decibels, restricting deployment to short data center interconnects and controlled environments.

These requirements assume ideal coherent detection with full digital signal processing compensation for linear impairments. Real implementations suffer penalties from transmitter and receiver imperfections including IQ imbalance, skew, quantization noise, and finite equalization. Implementation penalties typically add 2 to 4 decibels to theoretical requirements. Additionally, fiber nonlinear effects introduce OSNR-independent degradation that worsens with increasing launch power. For higher-order QAM, nonlinearity may force operation at OSNR values several decibels above the noise floor, wasting potential margin and further limiting reach.

7. Practical System Design Considerations

7.1 Adaptive Modulation Implementation

Modern optical networks increasingly deploy transceivers capable of adapting their modulation format based on measured link conditions. A single transceiver design might operate at DP-64QAM for a pristine 40 kilometer data center link achieving 800 Gigabits per second, then fall back to DP-32QAM for a 120 kilometer metro span delivering 650 Gigabits per second, and finally to DP-QPSK for degraded conditions maintaining 200 Gigabits per second connectivity. This flexibility maximizes network utilization while ensuring service availability across varying path quality.

The implementation combines adaptive modulation with variable forward error correction overhead to create a continuous range of achievable rates. Rather than discrete steps between format orders, the system adjusts both modulation and FEC code rate smoothly. Probabilistic constellation shaping enhances this capability further, allowing fine-grained rate adaptation without changing physical modulation order. A 64-QAM system might operate from 450 to 750 Gigabits per second by varying shaping entropy alone, adapting to OSNR conditions without hardware reconfiguration.

The control algorithms monitor link quality indicators including pre-FEC bit error rate, post-FEC frame error rate, received OSNR estimates, and error vector magnitude. Based on these measurements and network policy, the system selects appropriate modulation and coding parameters to maximize throughput while maintaining target error performance. Some implementations coordinate with network management systems to balance capacity across multiple paths, shifting traffic to higher-capacity formats when conditions allow and protecting critical services with robust low-order formats when needed.

7.2 Digital Signal Processing Complexity

The computational requirements for coherent demodulation scale dramatically with modulation order, impacting both ASIC design and power consumption. QPSK systems require relatively straightforward algorithms for chromatic dispersion compensation, adaptive equalization, carrier recovery, and timing synchronization. The DSP complexity typically consumes 2 to 3 watts for a single-wavelength 100 Gigabit transceiver. As we progress to 16-QAM and 64-QAM, the required precision increases, equalization tap counts grow, and carrier recovery becomes more demanding.

Chromatic dispersion compensation using frequency domain equalization represents a major computational burden, requiring fast Fourier transforms operating at symbol rate on blocks of hundreds or thousands of samples. For 64 Gbaud operation, this alone demands over 100 giga-operations per second. Adaptive equalization for polarization demultiplexing uses time-domain finite impulse response filters with typically 25 to 100 taps per butterfly arm, requiring constant multiply-accumulate operations at multi-gigahertz rates. Higher-order formats need longer filters and more frequent updates to track channel variations.

Carrier phase recovery complexity scales especially poorly with modulation order. QPSK allows simple Viterbi-Viterbi algorithms exploiting 90-degree rotational symmetry. For 16-QAM, decision-directed phase-locked loops become necessary, requiring symbol decisions, phase error calculation, and loop filtering at full symbol rate. By 64-QAM, pilot-aided estimation or blind phase search algorithms may be required, multiplying computational load. The total DSP power consumption can exceed 30 watts for 800 Gigabit per wavelength systems using DP-64QAM, dominating the overall transceiver power budget and driving thermal management requirements.

7.3 Transmitter and Receiver Impairments

Figure: Complete coherent optical transmission chain showing signal flow from data input through modulation, fiber impairments, and coherent detection. Bottom panels illustrate how different impairment types manifest in received constellation patterns, enabling diagnostic troubleshooting.

Real optical transceivers suffer numerous imperfections that degrade constellation quality and reduce effective OSNR margin. At the transmitter, digital-to-analog converters introduce quantization noise with magnitude inversely related to effective number of bits. Modern DACs achieve 5 to 6 effective bits at 60 gigasamples per second, providing adequate dynamic range for 16-QAM but barely sufficient for 64-QAM. The IQ modulator itself exhibits amplitude and phase imbalance between I and Q arms, skew between electrical and optical paths, and nonlinear transfer functions that distort constellation points.

Laser linewidth contributes phase noise that manifests as rotational spreading of the constellation. For QPSK, linewidths below 1 megahertz suffice with adequate carrier recovery algorithms. Higher-order formats with reduced symbol spacing demand progressively narrower linewidths, with 64-QAM systems typically requiring external cavity lasers achieving 100 kilohertz or less. The local oscillator at the coherent receiver adds additional phase noise that must be tracked and removed. The combined linewidth requirement becomes more stringent as constellation density increases.

Receiver impairments mirror those at the transmitter with analog-to-digital converters, photodetector nonlinearity, and finite resolution. Timing skew between I and Q paths or between X and Y polarizations rotates or shears the constellation. Amplifier transimpedance and automatic gain control circuits may introduce amplitude distortion. All these effects accumulate to create implementation penalties that erode theoretical performance. Careful transceiver design, calibration, and DSP-based impairment compensation mitigate these issues, but residual effects typically cost 2 to 4 decibels in OSNR requirement, directly impacting maximum transmission distance.

8. Application-Driven Format Selection

8.1 Long-Haul Submarine Systems

Undersea cable systems spanning thousands of kilometers across ocean basins operate under uniquely challenging conditions that dictate conservative modulation choices. The accumulated amplified spontaneous emission noise from dozens of inline optical amplifiers limits available OSNR at the receiver. Cable repair requires expensive ship operations making reliability paramount. These factors drive submarine systems toward DP-QPSK or in some cases DP-BPSK despite the spectral efficiency penalty.

Modern submarine cables achieve 20 to 30 terabits per second capacity using dense wavelength division multiplexing with hundreds of wavelength channels rather than aggressive per-wavelength modulation. Each wavelength carries 100 to 200 Gigabits per second using DP-QPSK with soft-decision forward error correction providing 11 to 12 decibels of coding gain. The robust modulation format tolerates aging components, temperature variations, and slow degradation over the 25-year design lifetime. The constant envelope property resists fiber nonlinearity even at the high launch powers needed to overcome attenuation between amplifiers spaced 50 to 100 kilometers apart.

Future submarine systems may adopt DP-8QAM with probabilistic shaping to increase per-wavelength capacity toward 300 Gigabits per second. However, the ultra-conservative deployment philosophy and need for interoperability across multiple cable landing stations make format evolution slow. Proven technologies with decades of operational experience win out over bleeding-edge modulation schemes that might offer theoretical gains but introduce new failure modes or compatibility issues.

8.2 Metro and Data Center Networks

Metropolitan networks and data center interconnects operate under radically different constraints that enable aggressive high-order modulation. Distances typically stay below 200 kilometers, sometimes as short as 1 to 10 kilometers for campus or inter-building connections. The fiber plant uses modern low-PMD cable with known characteristics. Available OSNR often exceeds requirements for even the highest modulation orders. Cost per gigabit and power consumption become primary optimization targets rather than maximizing reach.

These environments have driven rapid adoption of DP-16QAM and DP-64QAM formats. A 400 Gigabit transceiver using DP-16QAM at 60 Gbaud provides excellent performance over 80 to 120 kilometer metro distances with standard single-mode fiber. For data center interconnects under 40 kilometers, DP-64QAM enables 800 Gigabits per second at similar symbol rates, doubling capacity without requiring new fiber infrastructure. The high spectral efficiency reduces the wavelength count needed, lowering multiplexer costs and simplifying wavelength management.

The key enabler involves matching modulation order to actual link conditions rather than designing for worst-case scenarios. A metro network might use DP-QPSK for its longest 200-kilometer tier-1 to tier-2 connections, DP-16QAM for 80-kilometer tier-2 to tier-3 links, and DP-64QAM for short intra-datacenter connections. This zoned approach optimizes capacity investment while ensuring adequate margin everywhere. Network management systems can dynamically adjust formats as fiber ages or new paths are added, maximizing flexibility and future-proofing the infrastructure.

9. Future Directions and Research Frontiers

9.1 Machine Learning for Modulation Optimization

Artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques are beginning to revolutionize both constellation design and signal processing for optical communications. Neural networks can learn optimal demodulation and equalization functions that outperform traditional algorithms when impairment combinations become complex. End-to-end learning approaches optimize transmitter, channel, and receiver jointly, potentially discovering novel constellation shapes and processing strategies that exceed human-designed systems.

Research demonstrations have shown neural network-based equalizers achieving 1 to 2 decibel performance improvement over conventional butterfly structures in highly nonlinear regimes. Reinforcement learning agents can adapt modulation format and FEC parameters to maximize throughput across varying channel conditions without explicit programming of decision rules. Generative adversarial networks have designed unconventional constellation geometries with properties superior to standard QAM for specific impairment profiles.

However, significant barriers remain before these techniques reach commercial deployment. The computational requirements for inference often exceed those of conventional DSP, negating power consumption benefits. More critically, the black-box nature of neural networks makes verification of reliability across all operating conditions extremely difficult. A network might achieve excellent average performance while exhibiting catastrophic failure modes under rare combinations of impairments. The conservative nature of telecommunications deployment and the need for interoperability across vendors will likely confine machine learning to augmenting rather than replacing established modulation formats and algorithms for the foreseeable future.

9.2 Spatial Mode Multiplexing Integration

Extending beyond polarization multiplexing, spatial mode multiplexing uses multiple spatial modes in few-mode or multicore fibers to multiply capacity further. Each spatial mode can carry an independent modulation signal, with multiple-input multiple-output processing separating the modes at the receiver. Combined with advanced modulation, this approach could achieve tens of bits per symbol through the joint exploitation of amplitude, phase, polarization, and spatial dimensions.

Experimental systems have demonstrated transmission using 6 to 12 spatial modes combined with DP-16QAM or DP-QPSK modulation. The technical challenges involve mode-selective multiplexing and demultiplexing at transmitter and receiver, managing mode-dependent loss and group delay, and scaling MIMO processing to handle large channel matrices. As technology matures, commercial systems might adopt 2 to 4 spatial modes to double or quadruple fiber capacity without deploying new cable.

The constellation diagrams for spatial mode multiplexing extend into even higher dimensions, requiring projection onto lower-dimensional subspaces for visualization. The fundamental principles remain unchanged, with minimum Euclidean distance in the full dimensional space determining performance. However, the practical implementation complexity grows rapidly, and the benefits must justify the additional cost and power consumption compared to simply installing more fiber or using more wavelengths.

Summary

Optical modulation formats and their constellation diagrams form the theoretical and practical foundation of modern high-capacity fiber optic communications. This comprehensive guide has explored the spectrum from basic intensity modulation through sophisticated multi-dimensional QAM, examining the mathematical principles, geometric properties, and performance characteristics that determine system capabilities.

The fundamental trade-off between spectral efficiency and required signal-to-noise ratio pervades all modulation design. Each doubling of constellation size adds one bit per symbol but requires approximately 6 decibels additional OSNR. This relationship drives the application-specific selection of modulation orders, with robust DP-QPSK dominating long-haul systems, DP-16QAM optimizing metro networks, and DP-64QAM enabling maximum capacity in short-reach data center interconnects.

Advanced techniques including probabilistic constellation shaping, geometric optimization, and adaptive coding bring systems closer to fundamental Shannon limits. Digital signal processing enables these sophisticated formats through chromatic dispersion compensation, polarization demultiplexing, and carrier recovery algorithms whose complexity scales with modulation order. The constellation diagram emerges not merely as a visualization tool but as the complete mathematical representation capturing all essential properties of the signaling scheme.

Looking forward, optical communications will continue pushing toward higher orders of modulation combined with increasingly capable signal processing. The combination of machine learning, spatial mode multiplexing, and novel constellation geometries promises further gains. However, the fundamental geometric relationships revealed through constellation analysis will continue guiding system design, performance prediction, and optimization regardless of specific technological implementations.

References

[1] ITU-T Recommendation G.698.2 - Amplified multichannel dense wavelength division multiplexing applications with single channel optical interfaces

[2] IEEE 802.3ba - 40 Gigabit per second and 100 Gigabit per second Ethernet Standard

[3] E. Ip and J. M. Kahn, "Digital equalization of chromatic dispersion and polarization mode dispersion," Journal of Lightwave Technology

[4] F. Buchali et al., "Rate Adaptation and Reach Increase by Probabilistically Shaped 64-QAM: An Experimental Demonstration," Journal of Lightwave Technology

[5] K. Kikuchi, "Fundamentals of Coherent Optical Fiber Communications," Journal of Lightwave Technology

[6] M. Karlsson and E. Agrell, "Which is the most power-efficient modulation format in optical links?" Optics Express

[7] G. Ungerboeck, "Channel coding with multilevel/phase signals," IEEE Transactions on Information Theory

[8] OIF Implementation Agreement for Coherent Transmission Modules (400ZR and derivatives)

Sanjay Yadav, "Optical Network Communications: An Engineer's Perspective" – Bridge the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Optical Networking

Developed by MapYourTech Team

For educational purposes in Optical Networking Communications Technologies

Note: This guide is based on industry standards, best practices, and real-world implementation experiences in optical communications. Specific implementations may vary based on equipment vendors, network topology, fiber characteristics, and system requirements. Always consult with qualified network engineers and follow vendor documentation for actual deployments.

Feedback Welcome: If you have any suggestions, corrections, or improvements to propose, please feel free to write to us at feedback@mapyourtech.com

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here