22 min read

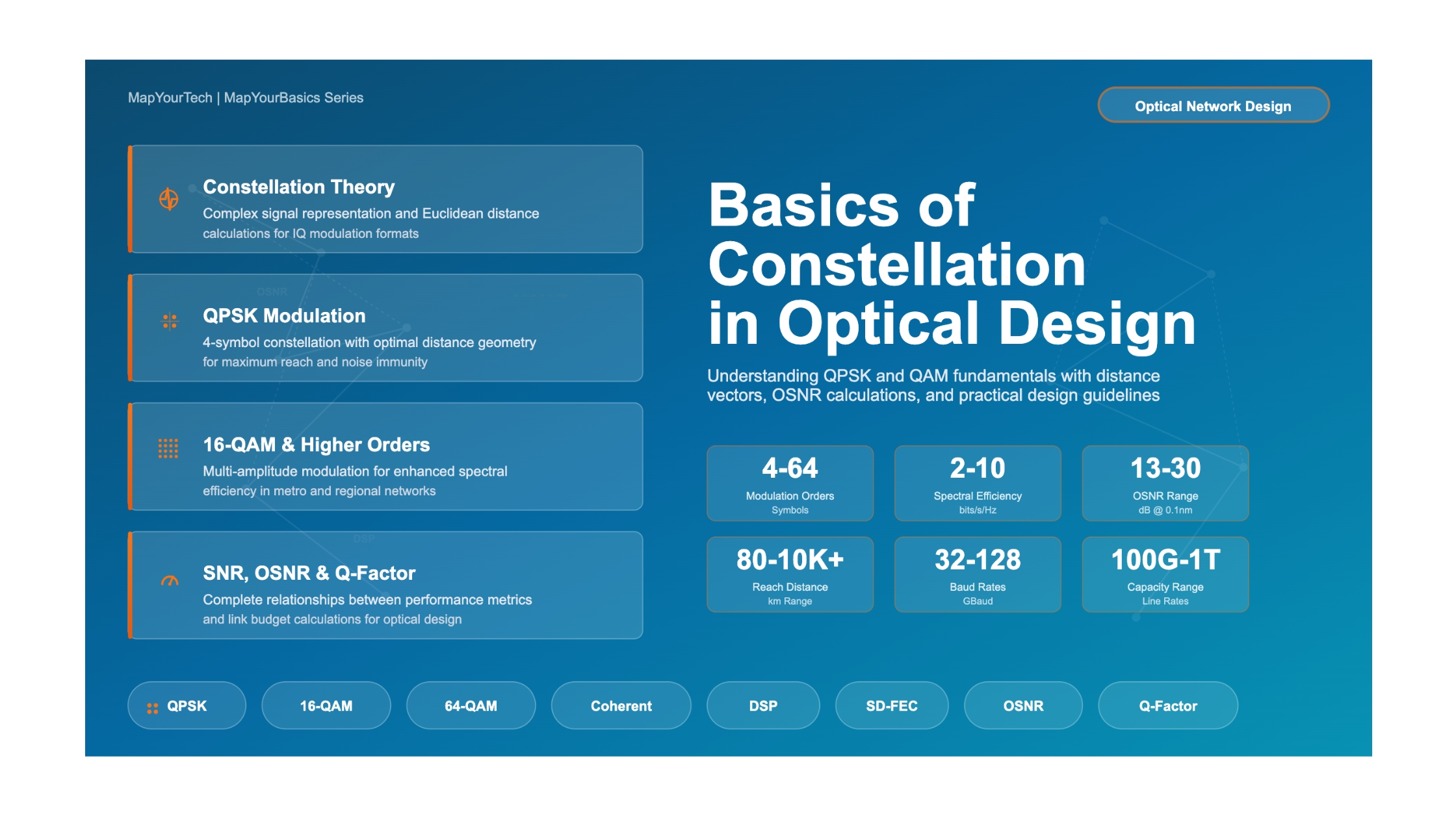

Basics of Constellation Diagrams in Optical Design: Understanding QPSK and QAM Fundamentals

Introduction

Constellation diagrams serve as the foundational visualization tool for understanding digital modulation formats in coherent optical communication systems. These diagrams map the complex amplitude and phase states of transmitted symbols onto a two-dimensional coordinate system, with the in-phase (I) component on the horizontal axis and the quadrature (Q) component on the vertical axis. For optical design engineers working with 100G, 400G, and beyond transmission systems, a deep understanding of constellation geometry directly translates to the ability to predict system performance, calculate link budgets, and optimize network capacity.

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Quadrature Phase-Shift Keying (QPSK) and Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) constellations, focusing on the mathematical relationships between constellation geometry, Euclidean distance, symbol energy, and critical performance metrics including Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Optical Signal-to-Noise Ratio (OSNR), and Q-factor. Each concept is illustrated with detailed diagrams showing distance vectors, worked calculations, and practical design guidelines that enable engineers to make informed decisions during system planning and troubleshooting.

1. Fundamental Constellation Theory

1.1 Complex Signal Representation

In coherent optical systems, each transmitted symbol is represented as a complex number in the IQ plane. The constellation point at position (I, Q) corresponds to an optical field with specific amplitude and phase characteristics. The mathematical representation of a symbol sk can be expressed as a point in two-dimensional Euclidean space.

Symbol Representation

sk = Ik + j·Qk = Ak · ejφk

Where:

Ik = In-phase component

Qk = Quadrature component

Ak = Amplitude = √(Ik2 + Qk2)

φk = Phase = arctan(Qk/Ik)1.2 Euclidean Distance: The Key Performance Parameter

The Euclidean distance between two constellation points determines the system's ability to distinguish between symbols in the presence of noise. Larger distances provide better noise immunity, while smaller distances allow for higher spectral efficiency at the cost of requiring higher OSNR. The minimum Euclidean distance dmin is the most critical parameter for predicting bit error rate (BER) performance.

Euclidean Distance Between Symbols

dij = |si - sj| = √[(Ii - Ij)2 + (Qi - Qj)2]

dmin = min(dij) for all i ≠ j

This minimum distance directly determines:

• Required OSNR for target BER

• Maximum transmission distance

• Tolerance to fiber impairments2. QPSK Constellation: Detailed Analysis

2.1 QPSK Constellation Geometry

Quadrature Phase-Shift Keying (QPSK) uses four constellation points positioned at the corners of a square, each representing 2 bits of information. The constellation is optimally configured with points at equal distances from the origin, maximizing the minimum Euclidean distance for a given average symbol power. This configuration provides excellent noise immunity while maintaining moderate spectral efficiency of 2 bits/symbol.

2.2 QPSK Symbol Energy and Distance Relationships

QPSK Symbol Energy Calculation

For normalized QPSK (amplitude = 1/√2 per dimension):

Es = (1/√2)2 + (1/√2)2 = 1/2 + 1/2 = 1

dmin = 2 × (1/√2) = √2 ≈ 1.414

Bit Energy (2 bits per symbol):

Eb = Es / log2(M) = 1 / 2 = 0.5

Asymptotic Power Efficiency:

γ = dmin2 / (4 × Eb) = 2 / (4 × 0.5) = 1 (or 0 dB)Where:

Es = Average symbol energy (normalized to 1)

Eb = Energy per bit

M = Number of constellation points (4 for QPSK)

dmin = Minimum Euclidean distance between symbols

γ = Asymptotic power efficiency in linear scale

3. 16-QAM Constellation: Detailed Analysis

3.1 16-QAM Constellation Geometry

16-QAM uses 16 constellation points arranged in a 4×4 square grid, with each symbol representing 4 bits of information. This configuration doubles the spectral efficiency compared to QPSK (4 bits/symbol vs 2 bits/symbol) but requires higher OSNR due to the reduced minimum distance between symbols. The constellation combines both amplitude and phase modulation, making it more susceptible to noise and nonlinear impairments but ideal for metro and regional networks where capacity is critical and distances are moderate.

3.2 16-QAM Symbol Energy Distribution

Critical Insight: Non-Uniform Energy Distribution

Unlike QPSK where all symbols have identical energy, 16-QAM has three distinct energy levels. The inner 4 points have energy of 2, the 8 edge points have energy of 10, and the 4 corner points have energy of 18. This non-uniform distribution makes 16-QAM more susceptible to amplitude noise and requires careful power optimization to balance performance between different symbol positions in the constellation.

4. SNR, OSNR, and GOSNR Relationships

4.1 From Electrical SNR to Optical OSNR

Understanding the relationship between electrical Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) measured at the coherent receiver and Optical Signal-to-Noise Ratio (OSNR) measured in the optical domain is essential for optical link design. The conversion between these parameters depends on the receiver bandwidth, baud rate, and reference bandwidth used for OSNR measurement.

SNR to OSNR Conversion

For coherent detection with polarization multiplexing:

SNR = Ps / (Nspans × NASE × Be)

OSNRBref = SNR × (Rs / Bref)

Standard conversion (assuming Nyquist matched filters):

SNR = OSNRBref × (Bref / Belec)

For Nyquist filtering where Belec = Rs/2:

SNR = OSNR12.5GHz × (12.5 GHz / (Rs/2))

Example for 32 Gbaud system:

SNR = OSNR12.5GHz × (12.5 / 16)

SNRdB = OSNRdB - 1.07 dBWhere:

SNR = Electrical signal-to-noise ratio at receiver

OSNRBref = Optical SNR measured in reference bandwidth (typically 12.5 GHz or 0.1 nm)

Ps = Signal power per polarization

NASE = Amplified spontaneous emission noise power spectral density

Be = Receiver electrical bandwidth

Rs = Symbol rate (baud rate)

Bref = Reference optical bandwidth (12.5 GHz standard)

4.2 GOSNR: Generalized OSNR Accounting for All Impairments

Generalized OSNR (GOSNR) extends the traditional OSNR concept by incorporating all sources of signal degradation in the optical link, not just ASE noise from amplifiers. This provides a more accurate prediction of system performance in real-world deployments where multiple impairment sources interact.

GOSNR Calculation Including All Impairments

1 / GOSNR = 1/OSNRASE + 1/SNRTRx + 1/SNRNL + 1/SNRX

In dB (approximation for small penalties):

GOSNRdB ≈ OSNRASE,dB - 10×log10(1 + 10(-SNRTRx,dB/10) + ...)

Practical example for 400G-ZR at 1000 km:

OSNRASE = 18.5 dB (amplifier noise)

SNRTRx = 30 dB (transceiver impairments, ~0.4 dB penalty)

SNRNL = 25 dB (fiber nonlinearity, ~0.7 dB penalty)

SNRX = 28 dB (crosstalk/filtering, ~0.5 dB penalty)

GOSNR ≈ 16.9 dB (total ~1.6 dB penalty from OSNRASE)Impairment Sources:

OSNRASE = ASE noise from optical amplifiers (EDFAs, Raman)

SNRTRx = Transceiver imperfections (laser phase noise, DAC/ADC quantization, IQ imbalance)

SNRNL = Fiber nonlinearity (SPM, XPM, FWM) interacting with dispersion

SNRX = Crosstalk, filtering distortion, PMD, PDL

Design Guideline: OSNR Margin Allocation

When planning optical links, allocate OSNR margin for each impairment source:

• ASE noise: 0.5-1 dB margin for aging, component degradation

• Nonlinearity: Higher for QPSK (1-2 dB) than 16-QAM (0.5-1 dB) due to constant envelope

• Transceiver: 0.3-0.8 dB depending on DSP implementation quality

• Crosstalk/filtering: 0.3-0.6 dB per ROADM degree

Total system margin: typically 3-5 dB from ideal OSNR to deployed OSNR

5. Q-Factor and BER Relationships

5.1 Q-Factor Definition and Physical Meaning

The Q-factor (Quality factor) quantifies the signal quality by measuring the separation between signal levels relative to noise. In optical systems, it serves as a direct predictor of Bit Error Rate (BER) and provides a single figure of merit that optical engineers use to assess link performance. The Q-factor relates to the eye diagram opening and can be measured directly with real-time oscilloscopes or calculated from BER test equipment.

Understanding the eye diagram is essential for Q-factor measurement because it provides a visual representation of all the information needed to calculate signal quality. The eye diagram displays superimposed traces of multiple bit periods, creating a pattern that resembles an eye. The vertical opening of the eye represents the voltage margin against noise, while the horizontal opening indicates timing margin against jitter. The Q-factor specifically quantifies the vertical eye opening by comparing the separation between the mean voltage levels of logic 1 and logic 0 states relative to their combined noise levels.

Eye Diagram Interpretation for Q-Factor Measurement:

The eye diagram reveals critical information about signal quality through its geometric properties. A wide-open eye with thick horizontal bands at the top and bottom indicates healthy logic 1 and logic 0 levels with minimal noise (large Q-factor). The vertical eye opening represents the voltage margin, which directly determines the Q-factor value. When measuring Q-factor from an oscilloscope, engineers typically use histogram measurements at the optimal sampling instant (maximum eye opening) to extract the mean values (μ₁, μ₀) and standard deviations (σ₁, σ₀) of each logic level.

For a high-quality signal, the Gaussian distributions of logic 1 and logic 0 states should be well-separated with minimal overlap. The Q-factor of 6 (15.6 dB) corresponds to approximately 10-9 BER, meaning the tails of these Gaussian distributions have negligible overlap at the decision threshold. In coherent optical systems, the same principle applies but in the IQ constellation space, where Q-factor relates to the separation between constellation points relative to noise clouds around each symbol.

Q-Factor Definition and BER Relationship

For binary modulation (on-off keying):

Q = (μ1 - μ0) / (σ1 + σ0)

For coherent detection (QPSK, QAM):

BER = (1/2) × erfc(Q / √2)

Inverting to find Q from BER:

Q = √2 × erfc-1(2 × BER)

Q-factor in dB scale:

Q2dB = 10 × log10(Q2) = 20 × log10(Q)

Relationship to minimum distance (AWGN channel):

Q = dmin / (2σ)

Where σ is noise standard deviationPractical Q-Factor Measurement Techniques:

Method 1: Oscilloscope Histogram Analysis - Capture eye diagram at optimal sampling point, generate amplitude histograms for logic 1 and logic 0 levels, fit Gaussian distributions to extract μ₁, μ₀, σ₁, σ₀, then calculate Q = (μ₁ - μ₀)/(σ₁ + σ₀). This method provides direct visibility into signal quality but requires careful noise floor calibration.

Method 2: BER-to-Q Conversion - Measure pre-FEC BER using BERT (Bit Error Rate Tester), apply inverse complementary error function: Q = √2 × erfc-1(2×BER). This method is accurate but requires sufficient errors to accumulate for statistical validity, typically measuring at least 100-1000 errors.

Method 3: Coherent Receiver EVM - In coherent systems, measure Error Vector Magnitude (EVM) of equalized constellation, convert to SNR, then to Q-factor. Modern coherent transponders provide this measurement in real-time through their DSP, enabling continuous link monitoring without external test equipment.

5.2 Q-Factor Calculation Examples for QPSK and 16-QAM

| BER Target | Q-Factor (linear) | Q² (dB) | Required OSNR (QPSK) | Required OSNR (16-QAM) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-2 | 2.00 | 6.0 dB | ~9 dB | ~13 dB | With 20% SD-FEC |

| 3.8×10-3 | 2.64 | 8.4 dB | ~11 dB | ~15 dB | With 7% SD-FEC |

| 10-3 | 3.09 | 9.8 dB | ~13 dB | ~17 dB | Pre-FEC standard |

| 10-9 | 6.00 | 15.6 dB | ~19 dB | ~23 dB | Post-FEC target |

| 10-12 | 7.03 | 16.9 dB | ~20 dB | ~24 dB | Error-free |

| 10-15 | 7.94 | 18.0 dB | ~21 dB | ~25 dB | High-reliability systems |

Important: FEC Overhead Considerations

The BER values shown above are pre-FEC (before Forward Error Correction). Modern coherent systems use SD-FEC (Soft-Decision FEC) codes that can correct errors from pre-FEC BER of 10-2 to post-FEC BER below 10-15. This coding gain of approximately 10-11 dB allows systems to operate at lower OSNR while maintaining error-free transmission. However, FEC adds overhead (typically 7-27%) that reduces net data rate.

5.3 QPSK BER Performance Formula

QPSK BER as Function of OSNR

For PM-QPSK (Polarization Multiplexed QPSK):

BER = (1/2) × erfc(√(SNR/2))

Converting SNR to OSNR (12.5 GHz reference, 32 Gbaud):

SNR = OSNR12.5GHz × (12.5 / 16)

BER = (1/2) × erfc(√(OSNR × 12.5/(2 × 16)))

Example calculation for OSNR = 15 dB:

OSNRlinear = 1015/10 = 31.62

SNR = 31.62 × 0.781 = 24.7

Q = √(24.7/2) = 3.51

BER = 0.5 × erfc(3.51/√2) ≈ 1.1 × 10-3

This BER is correctable with 7% SD-FEC to post-FEC BER < 10-156. Baud Rate, Spectral Efficiency, and Capacity Calculations

6.1 Fundamental Capacity Relationships

The data rate of a coherent optical system depends on three key parameters: baud rate (symbol rate), modulation format (bits per symbol), and polarization multiplexing. Understanding how these interact allows optical designers to optimize system capacity while managing OSNR requirements and spectral utilization.

Optical Capacity Calculation

Total Data Rate (before FEC):

Rtotal = Rs × log2(M) × Npol

Net Data Rate (after FEC):

Rnet = Rtotal × (1 - OHFEC)

Spectral Efficiency:

SE = Rnet / BWchannel (bits/s/Hz)

Example: 400G-ZR PM-16QAM System

Rs = 59 Gbaud

M = 16 (16-QAM, 4 bits/symbol)

Npol = 2 (polarization multiplexing)

OHFEC = 15% (SD-FEC overhead)

Rtotal = 59 × 4 × 2 = 472 Gb/s

Rnet = 472 × 0.85 = 401 Gb/s (meets 400GE spec)

SE = 401 / 75 = 5.35 bits/s/Hz (75 GHz channel)Where:

Rs = Symbol rate (baud rate) in GBaud

M = Modulation order (4 for QPSK, 16 for 16-QAM, 64 for 64-QAM)

Npol = Number of polarizations (1 or 2)

OHFEC = FEC overhead fraction (0.07 for 7%, 0.15 for 15%, 0.27 for 27%)

BWchannel = Optical channel bandwidth (50, 75, or 100 GHz typical)

6.2 Common System Configurations

| System Type | Modulation | Baud Rate | Bits/Symbol | FEC OH | Net Rate | SE | OSNR Req. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100G Long-Haul | PM-QPSK | 32 GBaud | 4 | 7% | 119 Gb/s | 2.38 b/s/Hz | 13-15 dB |

| 200G Metro | PM-QPSK | 64 GBaud | 4 | 15% | 218 Gb/s | 2.91 b/s/Hz | 15-17 dB |

| 200G Metro | PM-16QAM | 32 GBaud | 8 | 15% | 218 Gb/s | 4.36 b/s/Hz | 20-22 dB |

| 400G DCI (ZR) | PM-16QAM | 59 GBaud | 8 | 15% | 401 Gb/s | 5.35 b/s/Hz | 22-24 dB |

| 400G Long-Haul | PM-QPSK | 128 GBaud | 4 | 20% | 410 Gb/s | 4.10 b/s/Hz | 17-19 dB |

| 800G DCI | PM-64QAM | 90 GBaud | 12 | 15% | 918 Gb/s | 9.18 b/s/Hz | 28-30 dB |

7. Practical Design Example: Link Budget with Constellation Analysis

7.1 Complete Link Design Scenario

Design Scenario: 400G DWDM transmission over 800 km using PM-16QAM

Requirements:

• Target: 400 Gb/s net rate (400GE compatible)

• Distance: 800 km standard single-mode fiber (SSMF)

• Channel spacing: 75 GHz (C-band DWDM)

• Amplifier spacing: 80 km (10 spans)

• Target pre-FEC BER: 3.8×10-3 (correctable with 15% SD-FEC)

Step-by-Step Link Budget Calculation

Step 1: Determine Required Q-Factor and SNR

BERtarget = 3.8 × 10-3

Qreq = √2 × erfc-1(2 × 3.8×10-3) ≈ 2.64

Q2dB = 8.4 dB

Step 2: Calculate Required Symbol Rate

Rnet = 400 Gb/s

FEC overhead = 15%

Rtotal = 400 / 0.85 = 470.6 Gb/s

Rs = 470.6 / (4 bits/symbol × 2 pol) = 58.8 GBaud

Step 3: Convert Q-Factor to Required OSNR for 16-QAM

For 16-QAM, power efficiency γ = 0.4 (-4 dB)

SNRreq = Q2 / (2 × γ) = 6.97 / (2 × 0.4) = 8.71 (9.4 dB)

Convert to OSNR (12.5 GHz reference, 59 Gbaud):

OSNRreq = SNR × (Rs/2) / Bref

OSNRreq = 8.71 × 29.4 / 12.5 = 20.5 (13.1 dB)

Add implementation penalty (~2 dB):

OSNRreq,practical = 15.1 dB

Step 4: Calculate Available OSNR from Link

Ptx = 0 dBm (transmit power per channel)

Span loss = 0.2 dB/km × 80 km = 16 dB

EDFA gain = 16 dB (exactly compensates loss)

EDFA NF = 5.5 dB

Nspans = 10

OSNR after N spans (simplified):

OSNRN = Ptx + 58 - NF - 10×log10(Nspans)

OSNR10 = 0 + 58 - 5.5 - 10 = 42.5 dB

Wait - this seems too high! Let's use the proper formula:

OSNRASE = Psignal / (N × NF × h × ν × Bref)

Using standard formula: OSNR = 58 + Pch - NF - 10log(N)

OSNRASE = 58 + 0 - 5.5 - 10 = 42.5 dB

Subtract nonlinearity penalty (~1.5 dB for 16-QAM):

OSNRavailable ≈ 41 dB

Step 5: Link Margin

Margin = OSNRavailable - OSNRreq

Margin = 41 - 15.1 = 25.9 dB ✓ Link is viable with large margin!Design Validation Checklist:

✓ Symbol rate (59 Gbaud) within DSP capabilities (up to 96 Gbaud typical)

✓ Spectral efficiency (5.4 b/s/Hz) fits in 75 GHz channel with guard bands

✓ Required OSNR (15.1 dB) achievable with standard EDFAs

✓ Large margin (25.9 dB) accommodates aging, repair, and component variations

✓ 16-QAM provides 2× capacity vs QPSK at the same baud rate

✓ 800 km distance suitable for regional/metro networks

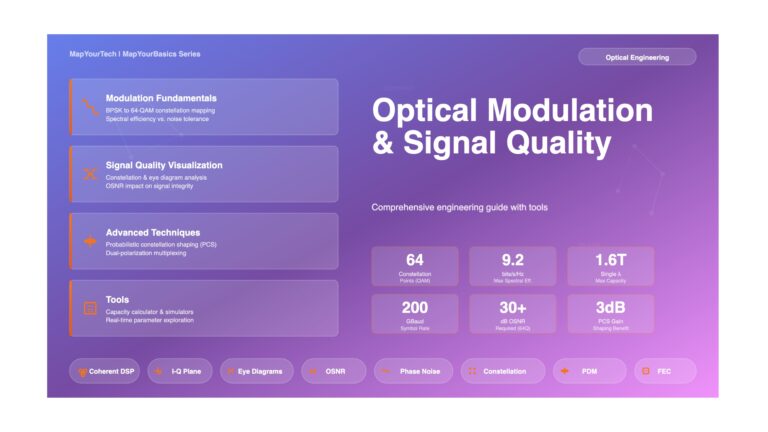

8. Advanced Topics: Probabilistic Constellation Shaping

8.1 Constellation Shaping Fundamentals

Probabilistic Constellation Shaping (PCS) represents an advanced technique where different constellation points are transmitted with non-uniform probabilities. By sending inner constellation points (with lower energy) more frequently than outer points (with higher energy), the average symbol energy decreases while maintaining the same minimum Euclidean distance. This approach provides a shaping gain of 1-1.5 dB in OSNR, effectively extending transmission distance or allowing operation in lower OSNR environments.

Shaping Gain Principle:

For 16-QAM with uniform distribution, Es,avg = 10. With optimal Gaussian-approximating shaping:

• Inner points (Es = 2): Probability ≈ 40%

• Edge points (Es = 10): Probability ≈ 50%

• Corner points (Es = 18): Probability ≈ 10%

• Shaped Es,avg ≈ 7.4 (vs 10 uniform) → 1.3 dB shaping gain

This gain comes "for free" through clever bit-to-symbol mapping without changing dmin or requiring higher transmit power!

9. Summary and Design Guidelines

9.1 Constellation Selection Flowchart

9.2 Quick Reference Table: Modulation Format Specifications

| Parameter | QPSK | 16-QAM | 64-QAM | Units / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constellation Points (M) | 4 | 16 | 64 | symbols |

| Bits per Symbol | 2 | 4 | 6 | bits/symbol |

| PM Bits per Symbol | 4 | 8 | 12 | bits/symbol (2 polarizations) |

| dmin (normalized) | √2 ≈ 1.414 | 2/√10 ≈ 0.632 | 2/√42 ≈ 0.309 | Es = 1 |

| Power Efficiency (γ) | 0 dB | -4.0 dB | -7.8 dB | relative to BPSK |

| Required OSNR @ 10-3 BER | 13-15 dB | 19-21 dB | 25-27 dB | typical with implementation |

| Typical Max Reach | 3,000-10,000+ km | 500-2,000 km | 80-500 km | depends on line rate |

| Nonlinearity Tolerance | Excellent | Good | Limited | constant vs multi-level envelope |

| Spectral Efficiency (PM) | 2-3 b/s/Hz | 4-6 b/s/Hz | 6-10 b/s/Hz | with typical FEC overhead |

| Typical Applications | 100G/200G/400G long-haul, submarine | 200G/400G metro, DCI | 400G/800G short-reach DCI | as of 2026 |

9.3 Essential Formulas for Optical Design Engineers

Complete Formula Reference Card

━━━ CONSTELLATION GEOMETRY ━━━

Euclidean Distance: dij = √[(Ii-Ij)2 + (Qi-Qj)2]

Symbol Energy: Es = I2 + Q2

Bit Energy: Eb = Es / log2(M)

━━━ SNR AND OSNR ━━━

SNR to OSNR: SNR = OSNRBref × (Bref / Belec)

OSNR after N spans: OSNRN,dB = 58 + Pch,dBm - NFdB - 10log10(N)

GOSNR: 1/GOSNR = 1/OSNRASE + 1/SNRTRx + 1/SNRNL + 1/SNRX

━━━ Q-FACTOR AND BER ━━━

BER from Q: BER = 0.5 × erfc(Q/√2)

Q from BER: Q = √2 × erfc-1(2×BER)

Q in dB: Q2dB = 20 × log10(Q)

━━━ CAPACITY AND SPECTRAL EFFICIENCY ━━━

Total Rate: Rtotal = Rs × log2(M) × Npol

Net Rate: Rnet = Rtotal × (1 - OHFEC)

Spectral Efficiency: SE = Rnet / BWchannel (bits/s/Hz)

━━━ POWER EFFICIENCY ━━━

γ (linear): γ = dmin2 / (4 × Eb)

γ (dB): γdB = 10 × log10(γ)

━━━ QUICK REFERENCE VALUES ━━━

QPSK: dmin = √2, γ = 0 dB, 2 bits/sym

16-QAM: dmin = 2/√10, γ = -4 dB, 4 bits/sym

64-QAM: dmin = 2/√42, γ = -7.8 dB, 6 bits/symConclusion

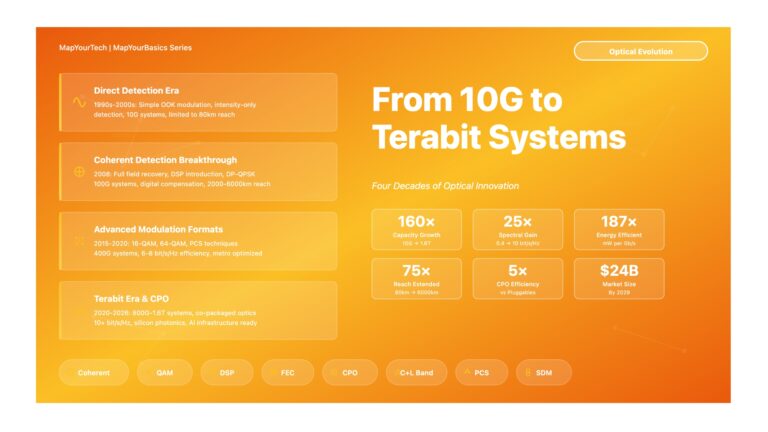

Understanding constellation diagrams and their mathematical properties is fundamental to optical network design. The choice between QPSK, 16-QAM, 64-QAM, or higher-order formats directly impacts system capacity, reach, OSNR requirements, and nonlinearity tolerance. By mastering the relationships between Euclidean distance, symbol energy, SNR, OSNR, Q-factor, and BER, optical design engineers can accurately predict link performance, optimize power budgets, and make informed trade-offs between spectral efficiency and transmission distance.

The key takeaways for practical design work include recognizing that QPSK provides the best reach and noise tolerance due to its large minimum Euclidean distance and constant envelope, making it ideal for long-haul and submarine applications up to 10,000+ km. 16-QAM doubles the spectral efficiency at the cost of approximately 5-6 dB additional OSNR requirement, positioning it optimally for metro and regional networks in the 500-2,000 km range. Higher-order formats like 64-QAM enable maximum capacity in short-reach data center interconnect scenarios where OSNR can exceed 25-30 dB.

Modern coherent systems increasingly employ probabilistic constellation shaping to achieve 1-1.5 dB of additional shaping gain, effectively extending reach or enabling operation at lower OSNR without changing the minimum Euclidean distance. This technique, combined with advanced soft-decision FEC codes that can correct from pre-FEC BER of 10-2 to post-FEC BER below 10-15, provides the flexibility to adapt transmission systems to varying link conditions while maintaining error-free operation.

As optical networks continue evolving toward 800G, 1.6T, and beyond, the principles detailed in this article remain foundational. Whether designing new networks or troubleshooting existing deployments, a solid grasp of constellation geometry, distance vectors, and performance metrics enables engineers to optimize capacity, reach, and reliability across the full spectrum of optical networking applications.

For a comprehensive exploration of coherent optical communications, advanced modulation techniques, and digital signal processing:

Sanjay Yadav, "Optical Network Communications: An Engineer's Perspective" – Bridge the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Optical Networking

Developed by MapYourTech Team

For educational purposes in Optical Networking Communications Technologies

Note: This guide is based on industry standards, best practices, and real-world implementation experiences. Specific implementations may vary based on equipment vendors, network topology, and regulatory requirements. Always consult with qualified network engineers and follow vendor documentation for actual deployments.

Feedback Welcome: If you have any suggestions, corrections, or improvements to propose, please feel free to write to us at feedback@mapyourtech.com

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here