39 min read

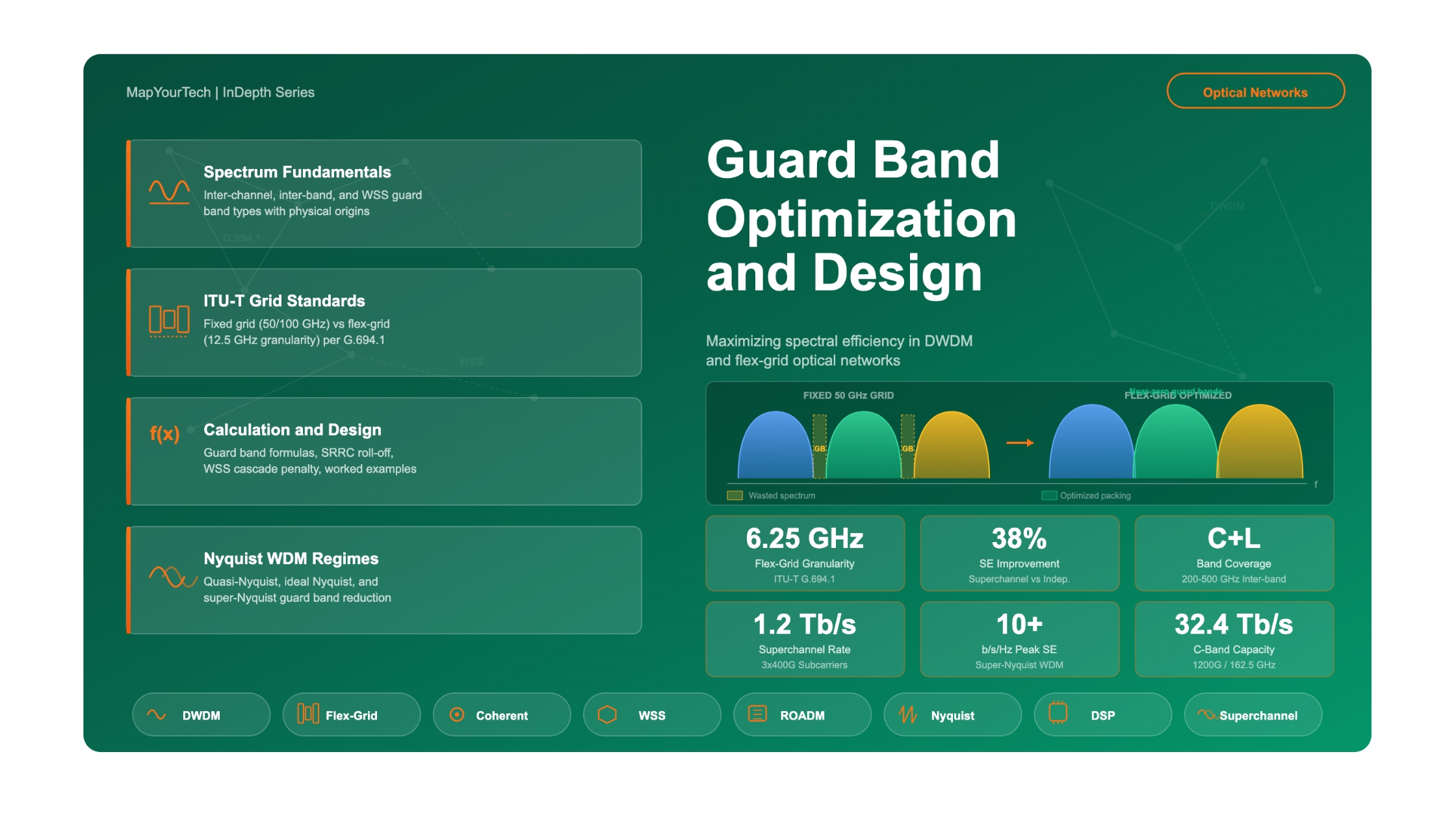

Guard Band Optimization and Design in Modern Optical Networks

Spectral Efficiency, Flex-Grid Planning, and Practical Guard Band Calculation for DWDM, Superchannel, and Elastic Optical Networks

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Fundamentals of Guard Bands in Optical Networks

- ITU-T Frequency Grid Standards and Guard Band Implications

- Guard Band Calculation Methods and Design Formulas

- Spectral Efficiency and Guard Band Trade-offs

- Flex-Grid Guard Band Optimization Strategies

- Real-World Design Examples and Case Studies

- Advanced Topics: Nyquist and Super-Nyquist Guard Band Reduction

- Future Directions

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

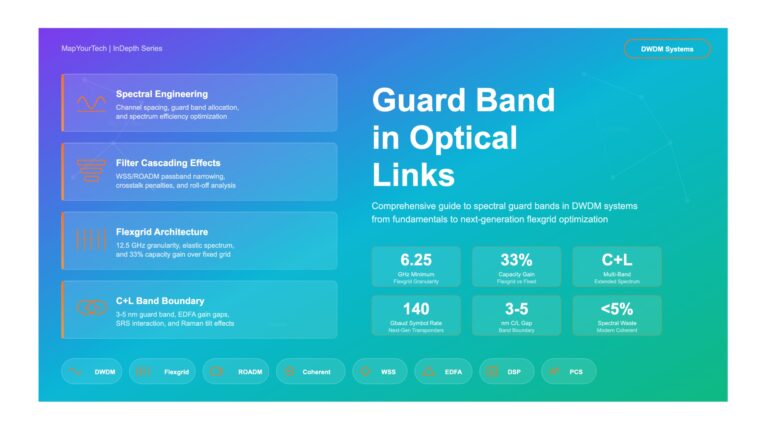

In Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing (DWDM) optical networks, every gigahertz of spectrum represents potential revenue-generating capacity. The guard band, the intentionally unused spectral gap between adjacent optical channels, is the necessary cost of preventing destructive interference between channels. Optimizing this guard band is one of the most effective levers network architects have for increasing total fiber capacity without deploying new infrastructure.

The evolution from fixed 100 GHz channel spacing to today's flexible 12.5 GHz slot-width grids represents a fundamental transformation in how optical spectrum is allocated and managed. Early DWDM systems allocated massive guard bands, sometimes 60-70% of the available channel slot was wasted spectral margin. Modern coherent systems with digital pulse shaping and high-performance wavelength selective switches (WSS) have reduced these margins dramatically, pushing channel spacing to within a few percent of the theoretical Nyquist limit.

Guard band design involves balancing multiple competing requirements. Reducing guard bands improves spectral efficiency and fiber capacity, but increases risks from filter-induced penalties, laser frequency drift, inter-channel crosstalk, and cascaded ROADM filtering effects. The optimal guard band depends on the modulation format, baud rate, filter technology, number of ROADM traversals, and the target system margin. Getting this balance right is critical for networks carrying 400G, 800G, and emerging 1.2T wavelengths.

This article provides a comprehensive technical analysis of guard band requirements, calculation methods, and optimization strategies across fixed-grid, flex-grid, and gridless network architectures. It draws on current industry standards (ITU-T G.694.1), transponder specifications, and real-world deployment data to present practical guidance for network design engineers. The treatment covers the mathematical foundations of Nyquist pulse shaping and roll-off factor effects, through to practical considerations such as WSS filter roll-off, cascaded ROADM penalties, and superchannel design trade-offs.

2. Fundamentals of Guard Bands in Optical Networks

2.1 What is a Guard Band?

A guard band is the unused spectral region between adjacent optical channels (or between groups of channels) in a WDM system. Its primary purpose is to prevent inter-channel crosstalk, the condition where energy from one channel leaks into the spectral space of a neighboring channel, degrading signal quality. The guard band provides sufficient separation so that practical filter implementations (both at the transmitter's pulse shaping and the network's WSS/ROADM filtering) can isolate each channel without significant penalty.

In the frequency domain, every modulated optical signal occupies a finite spectral bandwidth determined by its symbol rate and pulse shape. The ideal rectangular spectrum occupying exactly the Nyquist bandwidth (equal to the symbol rate Rs) is physically unrealizable because it would require an infinite-duration time-domain pulse. Practical implementations use pulse shapes with excess bandwidth, quantified by the roll-off factor, that extend beyond the Nyquist minimum. This excess bandwidth, combined with the finite steepness of optical and electrical filters, defines the minimum spectral separation needed between channels.

Guard bands can be categorized into several types based on where they appear in the optical spectrum:

The inter-channel guard band is the gap between individual wavelength channels within a DWDM system. In fixed-grid systems, this is the difference between the channel spacing and the actual spectral occupancy of the signal. For example, a 100G DP-QPSK signal at 28 Gbaud with roll-off factor 0.1 occupies approximately 30.8 GHz of spectrum. On a 50 GHz grid, this leaves approximately 19.2 GHz of guard band, roughly 38% of the slot wasted as spectral margin.

The inter-band guard band is the spectral gap between wavelength bands, such as between the C-band and L-band in a C+L system. This guard band accounts for the transition region of band-splitting filters and is typically 200-400 GHz (approximately 1.5-3 nm).

The ROADM filtering guard band is the additional spectral gap required between channels (or groups of channels) that are routed to different WSS output ports. Because WSS devices have a finite roll-off in their filtering function, an extra ~10-20 GHz of spectral guard band is needed between spectrally adjacent groups of channels directed to different ports.

Figure 3: Three categories of guard bands in DWDM systems — (A) Inter-channel guard bands between individual channels on a fixed grid, (B) Inter-band guard bands at the C/L-band boundary, and (C) WSS port boundary guard bands caused by finite filter roll-off.

The superchannel internal guard band is the spacing between subcarriers within a superchannel. Because subcarriers within a superchannel are inserted, transported, and extracted together (never individually filtered by intermediate ROADMs), their internal guard bands can be minimized to just the Nyquist spacing or even eliminated entirely using gridless/Nyquist-WDM techniques.

2.2 Physical Origins of Guard Band Requirements

Several physical mechanisms drive the need for guard bands in practical optical networks. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for proper guard band dimensioning.

Transmitter spectral leakage: No practical pulse-shaping filter produces a perfectly rectangular spectrum. The finite roll-off of root-raised-cosine (RRC) or similar pulse-shaping filters means that signal energy extends beyond the Nyquist bandwidth. For a signal with symbol rate Rs and roll-off factor ρ (rho), the total occupied bandwidth is Rs(1 + ρ). The AC1200 L-band transponder specifications confirm typical roll-off factor values of 0.1 as the minimum, with the maximum depending on baud rate: at 69 Gbaud the maximum roll-off is 0.3, while at 45 Gbaud it can reach 1.0. The transmitter optical spectrum width can be estimated as: Spectrum Width = Baud Rate x (1 + TX roll-off factor). At 69 Gbaud with 0.1 roll-off, this gives approximately 77 GHz of 20 dB bandwidth.

Laser frequency uncertainty: Tunable laser sources have a finite frequency accuracy relative to the ITU grid. The AC1200 specifies laser frequency stability of +/-1.5 GHz relative to the ITU grid, with fine tuning steps of 100 MHz or better. When two adjacent channels each have up to 1.5 GHz of frequency error in opposite directions, the effective channel spacing can be reduced by up to 3 GHz from the nominal value. This uncertainty must be absorbed by the guard band.

WSS filter transition bandwidth: Wavelength Selective Switches used in ROADMs do not have infinitely sharp filter edges. The transition from the passband to the stopband requires a finite spectral width, typically 5-15 GHz for modern WSS devices depending on the resolution and technology. This transition region creates an effective dead zone in the spectrum where neither the passed nor blocked channel can reliably occupy.

Cascaded filter narrowing: As a signal traverses multiple ROADMs, the effective passband narrows due to the cascaded effect of multiple WSS filters. Experimental data from 110 Gbaud super-Nyquist systems shows that after 10 ROADM cascades (each with 94.8 GHz 3 dB bandwidth), the effective 3 dB bandwidth narrows to approximately 84.5 GHz, a reduction of about 10 GHz. This progressive narrowing clips the edges of the signal spectrum, increasing OSNR penalty and effectively requiring more guard band to maintain performance.

Fiber nonlinear effects: Cross-phase modulation (XPM) and four-wave mixing (FWM) between adjacent channels generate interference products that can fall within the bandwidth of neighboring channels. Wider guard bands reduce these nonlinear penalties, particularly in systems with high per-channel launch powers. The effect is more pronounced for channels with tighter spacing and higher symbol rates.

2.3 Guard Band vs. Channel Spacing: Clarifying the Terminology

A common source of confusion is the difference between channel spacing and guard band. Channel spacing (Δf) is the frequency difference between the nominal center frequencies of adjacent channels. The guard band is the unused spectral region between the occupied bandwidths of adjacent channels. The relationship is:

Guard Band Calculation

Guard Band = Channel Spacing (Δf) - Signal Occupied Bandwidth (BWocc)

Where:

BWocc = Rs x (1 + ρ)

Rs = Symbol rate (Gbaud)

ρ = Roll-off factor of the pulse-shaping filter (typically 0.05 - 0.2)

-- Example: 100G DP-QPSK at 28 Gbaud, roll-off = 0.1, on 50 GHz grid --

BWocc = 28 x (1 + 0.1) = 30.8 GHz

Guard Band = 50 - 30.8 = 19.2 GHz (38% of slot is guard band)

-- Example: 400G DP-16QAM at 63 Gbaud, roll-off = 0.1, on 75 GHz grid --

BWocc = 63 x (1 + 0.1) = 69.3 GHz

Guard Band = 75 - 69.3 = 5.7 GHz (7.6% of slot is guard band)

-- Example: 800G at 125 Gbaud, roll-off = 0.1, on 137.5 GHz grid --

BWocc = 125 x (1 + 0.1) = 137.5 GHz

Guard Band = 137.5 - 137.5 = 0 GHz (Nyquist-limit, no margin)

The normalized frequency spacing δf = Δf / Rs is a key design parameter. Three regimes are recognized in the literature. When δf is much greater than 1 (standard WDM), a large guard band exists and channels are fully isolated with no crosstalk. When δf equals approximately 1.0-1.2 (quasi-Nyquist WDM), channels are packed close to the theoretical limit with minimal guard band. When δf is less than 1 (super-Nyquist WDM), channel spectra overlap intentionally, requiring advanced DSP for crosstalk cancellation.

3. ITU-T Frequency Grid Standards and Guard Band Implications

3.1 Fixed Grid: 100 GHz, 50 GHz, 25 GHz, and 12.5 GHz

ITU-T Recommendation G.694.1 defines the frequency grid for DWDM applications. The fixed grid defines nominal central frequencies as 193.1 THz +/- n x spacing, where spacing can be 100 GHz, 50 GHz, 25 GHz, or 12.5 GHz. The 50 GHz grid has been the workhorse of the optical industry for over a decade, supporting up to 88 channels across the C-band (approximately 4.4 THz of spectrum from 191.3 to 196.1 THz).

The guard band implications of fixed grids are straightforward but limiting. Every channel receives the same spectral slot width regardless of its actual bandwidth requirement. A 10G signal on a 50 GHz grid wastes approximately 40 GHz of spectrum (80% of the slot), while a 400G signal at 64 Gbaud barely fits within the same 50 GHz slot. This spectral inefficiency becomes a critical capacity limiter as line rates increase beyond 100G.

| Line Rate | Modulation | Baud Rate (Gbaud) | Occupied BW (GHz) | Grid (GHz) | Guard Band (GHz) | Spectral Efficiency (b/s/Hz) | Guard Band % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10G | OOK | 10.7 | ~25 | 50 | ~25 | 0.2 | 50% |

| 100G | DP-QPSK | 28 | 30.8 | 50 | 19.2 | 2.0 | 38% |

| 200G | DP-16QAM | 28 | 30.8 | 50 | 19.2 | 4.0 | 38% |

| 400G | DP-16QAM | 63 | 69.3 | 75 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 7.6% |

| 400G | DP-QPSK | 125 | 137.5 | 150 | 12.5 | 2.7 | 8.3% |

| 800G | DP-16QAM | 125 | 137.5 | 150 | 12.5 | 5.3 | 8.3% |

| 1200G | DP-64QAM | 138 | 151.8 | 162.5 | 10.7 | 7.4 | 6.6% |

3.2 Flexible Grid per ITU-T G.694.1

Figure 4: Fixed grid vs flex-grid spectrum allocation for a mixed-rate deployment (100G, 400G, 800G). Flex-grid eliminates wasted spectrum by matching slot widths to actual signal bandwidth, enabling an extra 100G channel in the same total spectrum.

The 2012 revision of ITU-T G.694.1 (updated in 2020) introduced the flexible DWDM grid, which fundamentally changed guard band design. Instead of fixed channel slots, the flexible grid defines nominal central frequencies at intervals of 6.25 GHz from the reference frequency of 193.1 THz, expressed as: f = 193.1 + n x 0.00625 THz, where n is any positive or negative integer including zero.

The slot width is defined in multiples of 12.5 GHz: Slot Width = 12.5 x m GHz, where m is a positive integer. This means the minimum slot width is 12.5 GHz (m=1), and slots can be 12.5, 25, 37.5, 50, 62.5, 75 GHz and so on in 12.5 GHz steps.

The flexible grid enables significant guard band optimization because slot widths can be matched to the actual spectral occupancy of each channel. Instead of wasting spectrum by placing a 69 GHz wide 400G signal into a 100 GHz fixed slot, the flex-grid allows allocation of a 75 GHz slot (m=6), reducing guard band waste from 31 GHz to just 6 GHz. For networks deploying mixed line rates (100G, 200G, 400G, 800G on the same fiber), flex-grid can improve total capacity by 25-33% compared to 50 GHz fixed-grid systems.

3.3 Central Frequency Granularity and Slot Width

The 6.25 GHz granularity of the central frequency placement is a critical detail often overlooked. This granularity exists because it enables slots of odd and even multiples of 12.5 GHz to be placed adjacent to each other without spectral gaps. Consider a 37.5 GHz slot (m=3, an odd multiple) next to a 50 GHz slot (m=4, an even multiple). If central frequencies were only at 12.5 GHz granularity, a 6.25 GHz gap would appear between these slots. The 6.25 GHz central frequency granularity eliminates this gap.

However, devices and applications do not have to support every possible slot width or position. The standard explicitly allows subsets. For example, many deployed flex-grid ROADMs support only central frequency granularity of 12.5 GHz (even values of n) with slot widths in multiples of 12.5 or 25 GHz. This practical limitation affects guard band optimization: if the minimum slot width step is 12.5 GHz, a signal needing 70 GHz of spectrum must be allocated a 75 GHz slot (m=6) or 87.5 GHz (m=7), leaving 5 or 17.5 GHz of guard band respectively.

Design Consideration: The guard band achievable in a flex-grid network is quantized by the slot width granularity. With 12.5 GHz slot width steps, the minimum achievable guard band between the signal occupied bandwidth and the slot edge is 0 to 12.4 GHz, averaging approximately 6.25 GHz. This quantization effect means that practical flex-grid guard bands are always larger than the theoretical minimum.

4. Guard Band Calculation Methods and Design Formulas

4.1 Minimum Channel Spacing for Zero Crosstalk

For a WDM system using Nyquist-shaped pulses with square-root raised cosine (SRRC) pulse shaping at both transmitter and receiver, the minimum channel spacing for zero linear crosstalk is determined by the roll-off factor ρ:

Minimum Channel Spacing for Zero Crosstalk

Δfmin = Rs x (1 + ρ)

Where:

Δfmin = Minimum channel spacing for zero linear crosstalk (GHz)

Rs = Symbol rate (Gbaud)

ρ = Roll-off factor (0 to 1)

Therefore, the minimum guard band for zero crosstalk:

GBmin = Δfmin - Rs = Rs x ρ

-- Example: 64 Gbaud, ρ = 0.1 --

Δfmin = 64 x 1.1 = 70.4 GHz

GBmin = 64 x 0.1 = 6.4 GHz

-- Example: 125 Gbaud, ρ = 0.1 --

Δfmin = 125 x 1.1 = 137.5 GHz

GBmin = 125 x 0.1 = 12.5 GHz

This formula gives the theoretical minimum. In practice, additional guard band is needed to account for laser frequency uncertainty, filter imperfections, and cascaded ROADM effects. The AC1200 L-band specification provides direct guidance: for DP-QPSK and DP-P-16QAM at 35 Gbaud, neighboring channel crosstalk tolerance (1.0 dB OSNR penalty from two neighbors) requires channel spacing of 1.1 x baud rate for QPSK and P-16QAM, and 1.2 x baud rate for 16QAM. This confirms that higher-order modulation formats need larger guard bands due to their greater sensitivity to inter-channel crosstalk.

4.2 Guard Band as a Function of Roll-Off Factor

The roll-off factor ρ is the single most important parameter determining the minimum guard band. Research on coherent optical systems with SRRC pulse shaping shows the following SNR penalty behavior as a function of normalized frequency spacing δf = Δf/Rs:

For ρ = 0.1 (the most common value in modern coherent systems), no crosstalk penalty exists when δf > 1.1. For δf between 1.0 and 1.1, a small penalty appears that increases for higher-order modulation formats: QPSK shows negligible penalty at δf = 1.05, while 64QAM shows a measurable penalty at δf = 1.1. For δf < 1.0 (super-Nyquist regime), penalties increase rapidly and require advanced equalization.

Figure 1: SNR Penalty vs. Normalized Frequency Spacing for Different Modulation Formats (SRRC pulse shaping, ρ = 0.1)

The practical implication is that for most coherent systems with ρ = 0.1, setting Δf = 1.1 x Rs provides crosstalk-free operation for QPSK, while 16QAM may need Δf = 1.15-1.2 x Rs for zero penalty. The guard band is therefore: GB = (Δf/Rs - 1) x Rs = (δf - 1) x Rs.

4.3 WSS Filter-Induced Guard Bands

When channels are routed through wavelength selective switches in ROADMs, the WSS filtering function introduces additional guard band requirements. The WSS does not have a perfect brick-wall filter response; instead, it has a finite roll-off between the passband and the stopband. This is particularly important at the boundary between groups of channels directed to different WSS output ports.

In submarine cable SLTE systems, WSS filtering data shows that roughly an extra 20 GHz slot is necessary in practice between each spectrally successive group of channels connected to two different WSS ports. This guard band exists because of the non-ideal square filtering function of the WSS. For terrestrial ROADM networks with modern WSS technology, the WSS-induced guard band is typically 10-20 GHz, with minimum reconfigurable bandwidth step sizes of 6.25 or 12.5 GHz aligned to the ITU grid.

The WSS guard band is distinct from the inter-channel guard band. Within a group of channels all going to the same WSS port, channels can be packed at their normal Nyquist spacing. The extra WSS guard band only appears at the boundaries between different routing groups. This is why superchannel architectures, where all subcarriers are routed together, can achieve significantly better spectral efficiency than individually routed channels.

Total Guard Band Including WSS Filtering

For channels routed to the SAME WSS port (no WSS guard band):

GBtotal = Rs x ρ + Δflaser

For channels routed to DIFFERENT WSS ports:

GBtotal = Rs x ρ + Δflaser + GBWSS

Where:

Δflaser = 2 x laser frequency stability (typically 2 x 1.5 GHz = 3 GHz)

GBWSS = WSS filter transition guard band (10-20 GHz typical)

-- Example: 64 Gbaud, ρ = 0.1, channels at WSS boundary --

GBtotal = 6.4 + 3 + 15 = 24.4 GHz (at WSS port boundary)

GBtotal = 6.4 + 3 = 9.4 GHz (same WSS port)

4.4 Cascaded Filter Bandwidth Narrowing

As a signal passes through multiple ROADM nodes, each containing one or more WSS filters, the effective passband narrows progressively. This cascaded filtering effect is one of the most critical factors in guard band design for multi-node optical networks.

Experimental measurements from 110 Gbaud super-Nyquist WDM transmission over ROADM chains show that each WSS in the chain with a 94.8 GHz 3 dB bandwidth contributes to progressive narrowing. After 10 cascaded ROADMs, the 3 dB bandwidth reduces from 94.8 GHz to approximately 84.5 GHz, a narrowing of about 10 GHz. The OSNR penalty at the 7% HD-FEC threshold (BER = 3.8 x 10-3) remains below 0.8 dB for filtering bandwidths down to 84.6 GHz, demonstrating that super-Nyquist signals have inherently good tolerance to cascaded filtering.

The bandwidth narrowing per ROADM cascade can be approximated as:

Cascaded Filter Bandwidth Estimation

For N cascaded filters, each with a Gaussian-like passband:

BW3dB(N) = BW3dB(1) x N-0.5/n

Where:

BW3dB(1) = 3 dB bandwidth of a single filter

N = Number of cascaded filters

n = Filter order (n=2 for 2nd-order Gaussian typical WSS)

-- Example: 10 cascaded ROADMs, each with BW = 94.8 GHz, 2nd-order --

BW3dB(10) = 94.8 x 10-0.25 = 94.8 x 0.562 = ~53 GHz (theoretical)

Measured value: ~84.5 GHz (actual WSS is higher order than 2nd Gaussian)

-- Design Rule of Thumb --

For N ROADM passes, add approximately:

GBcascade = 1 to 1.5 GHz per ROADM to the guard band budget

The AX1200 CIM8 pluggable module specifies receiver performance assuming a net optical passband similar to a 2nd-order Gaussian filter with FWHM (full width at half maximum) greater than or equal to 200 GHz for 1200G operation. This specification implicitly accounts for cascaded filtering effects and defines the guard band budget that the network design must provide.

Key Takeaways: Guard Band Calculation

- Minimum guard band for zero crosstalk = Rs x ρ (e.g., 6.4 GHz for 64 Gbaud at ρ = 0.1)

- Add 3 GHz margin for laser frequency uncertainty (2 x 1.5 GHz worst case)

- Add 10-20 GHz at WSS port boundaries where channel groups are split

- Add ~1-1.5 GHz per ROADM cascade for bandwidth narrowing

- Higher-order modulation formats (16QAM, 64QAM) need wider guard bands than QPSK

5. Spectral Efficiency and Guard Band Trade-offs

5.1 Spectral Efficiency Metrics

Spectral efficiency (SE) measures how effectively the available optical spectrum is used to carry information. It is defined as the net information bit rate divided by the occupied spectral bandwidth, expressed in bits per second per Hertz (b/s/Hz). The maximum achievable SE in a WDM system is bounded by the Shannon limit, but in practice it is heavily influenced by the guard band between channels.

The relationship between guard band and spectral efficiency can be expressed as:

Spectral Efficiency and Guard Band Relationship

SEsystem = SEchannel x (BWocc / Δf)

SEsystem = SEchannel x (Rs(1+ρ) / (Rs(1+ρ) + GB))

Where:

SEchannel = Per-channel spectral efficiency (= log2(M) x 2 / (1 + FEC OH))

M = Modulation order (4 for QPSK, 16 for 16QAM, 64 for 64QAM)

GB = Guard band (GHz)

Spectral Efficiency Penalty from Guard Band:

SEpenalty = 1 - (BWocc / Δf) = GB / Δf

-- Example: 400G at 63 Gbaud, ρ = 0.1, on 75 GHz flex-grid slot --

SEchannel = log2(16) x 2 / (1 + 0.27) = 8 / 1.27 = 6.30 b/s/Hz (within channel BW)

SEsystem = 400 / 75 = 5.33 b/s/Hz (net system SE)

SEpenalty = (75 - 69.3) / 75 = 7.6%

5.2 Quantifying Guard Band Impact on Capacity

The total fiber capacity is: Ctotal = SEsystem x Btotal, where Btotal is the total available optical bandwidth (approximately 4.4 THz for C-band, 8-9 THz for C+L band). Every 1% reduction in guard band overhead translates directly to a 1% increase in total fiber capacity.

The following table shows the capacity impact across different guard band configurations using real transponder data from the AX1200 module specifications:

| Configuration | Line Rate | Baud Rate | Slot Width | Guard Band | Channels | Total Capacity | SE (b/s/Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400G / 75 GHz | 400G | 63 Gbaud | 75 GHz | 5.7 GHz | 58 | 23.2 Tb/s | 5.33 |

| 400G / 100 GHz | 400G | 88 Gbaud | 100 GHz | 3.2 GHz | 44 | 17.6 Tb/s | 4.00 |

| 600G / 112.5 GHz | 600G | 98 Gbaud | 112.5 GHz | 4.7 GHz | 39 | 23.4 Tb/s | 5.33 |

| 800G / 137.5 GHz | 800G | 125 Gbaud | 137.5 GHz | 0 GHz | 32 | 25.6 Tb/s | 5.82 |

| 800G / 150 GHz | 800G | 138 Gbaud | 150 GHz | ~2 GHz | 29 | 23.2 Tb/s | 5.33 |

| 1200G / 162.5 GHz | 1200G | 138 Gbaud | 162.5 GHz | 10.7 GHz | 27 | 32.4 Tb/s | 7.38 |

The data reveals that the highest total capacity comes from 1200G channels because their higher bits-per-symbol efficiency more than compensates for the slightly wider guard band. However, the 1200G configuration requires an OSNR of 31.3 dB (ZR mode), which limits its deployment to short-reach and metro applications. For long-haul networks, 400G at 75 GHz or 800G at 137.5 GHz represent optimal trade-offs between guard band efficiency and reach.

5.3 Modulation Format and Guard Band Interaction

Higher-order modulation formats are more sensitive to inter-channel crosstalk, requiring wider guard bands relative to lower-order formats at the same baud rate. This creates an important design tension: higher-order formats improve bits-per-symbol efficiency (reducing the baud rate needed for a given line rate), but require more guard band margin per unit of baud rate.

The normalized frequency spacing δf required for less than 1 dB crosstalk penalty varies by modulation format. For QPSK, δf = 1.05 is sufficient with SRRC ρ = 0.1. For 16QAM at the same roll-off, δf needs to be approximately 1.1-1.2 to maintain less than 1 dB penalty. For 64QAM, δf should be at least 1.15-1.25. This is confirmed by the AC1200 specifications which specify 1.1 x baud rate spacing for QPSK/P-16QAM and 1.2 x baud rate for 16QAM.

The design choice between a lower-order modulation at higher baud rate versus a higher-order modulation at lower baud rate has direct guard band implications. Consider 400G: using DP-QPSK at 125 Gbaud requires a 137.5 GHz slot (guard band ~ 0 GHz at Nyquist), while DP-16QAM at 63 Gbaud fits in a 75 GHz slot (guard band ~ 6 GHz). The 16QAM option is far more spectrally efficient (400G/75 GHz = 5.33 b/s/Hz vs. 400G/137.5 GHz = 2.91 b/s/Hz) but requires approximately 2 dB higher OSNR, reducing the maximum transmission reach.

Figure 2: C-Band Total Capacity vs. Guard Band Overhead for Different Transponder Configurations

6. Flex-Grid Guard Band Optimization Strategies

6.1 Variable Bandwidth Allocation

The most straightforward flex-grid optimization is matching the allocated spectrum slot to the actual signal bandwidth. In a fixed 50 GHz grid, a 400G signal at 63 Gbaud (69.3 GHz occupied bandwidth) cannot fit in a single 50 GHz slot and must use two slots (100 GHz total), wasting 30.7 GHz. On a flex-grid, the same signal fits in a 75 GHz slot (m=6), wasting only 5.7 GHz. This simple matching saves 25 GHz per channel, enough to add approximately one extra 400G channel for every three channels deployed on the same fiber.

For mixed-rate networks, variable bandwidth allocation provides even greater savings. Consider a fiber carrying a mix of 100G (30.8 GHz occupied, needing 37.5 GHz slot), 400G (69.3 GHz occupied, needing 75 GHz slot), and 800G (137.5 GHz occupied, needing 150 GHz slot) channels. On a fixed 50 GHz grid, the 400G and 800G channels require 2 and 3 fixed-grid slots respectively. On flex-grid, each channel gets precisely the spectrum it needs, improving total capacity by 25-33%.

The Routing, Modulation Level, and Spectrum Assignment (RMLSA) problem in flex-grid networks jointly optimizes three variables: the physical path, the modulation format (which determines the baud rate and spectral width), and the spectrum slot position. The guard band enters this optimization as a constraint: the assigned slot width must be at least BWocc + GBmin, rounded up to the nearest 12.5 GHz multiple. More advanced formulations also consider the physical impairments along the selected path to determine whether a higher-order modulation format (smaller slot, more guard band-efficient) can be used, or whether a more robust lower-order format (larger slot, less spectrally efficient) is needed.

6.2 Superchannel Design and Internal Guard Bands

Figure 5: Comparison of three independent 400G channels (225 GHz total) vs. a single 1.2T superchannel (162.5 GHz) — eliminating internal guard bands saves 62.5 GHz and improves spectral efficiency by 38%.

Superchannels represent one of the most effective approaches to guard band optimization. A superchannel consists of multiple optical subcarriers that are inserted, transported, and extracted together as a single unit. Because these subcarriers are never individually filtered by intermediate ROADMs, the WSS guard band between subcarriers within the superchannel can be eliminated entirely.

The internal spacing between subcarriers in a superchannel can be reduced to the bare Nyquist limit: Δf = Rs for ideal Nyquist shaping, or Δf = Rs(1 + ρ) for practical SRRC shaping. With ρ = 0.1, the internal guard band per subcarrier pair is just Rs x 0.1, compared to Rs x 0.1 + 10-20 GHz for individually routed channels at a WSS boundary.

Case Study: 1.2T Superchannel vs. Individual 400G Channels

Scenario: Deploy 1.2 Tb/s of capacity on a single fiber. Compare a 1.2T superchannel with three individual 400G channels.

Option A: Three Individual 400G Channels (75 GHz each)

Each 400G channel at 63 Gbaud occupies 69.3 GHz, allocated in a 75 GHz slot. Three channels need 3 x 75 = 225 GHz total. Between each pair of channels at a WSS boundary, add approximately 15 GHz of WSS guard band. Total spectrum: 225 + 2 x 15 = 255 GHz. Net spectral efficiency: 1200 / 255 = 4.71 b/s/Hz.

Option B: 1.2T Superchannel (three 400G subcarriers)

Three subcarriers at 63 Gbaud, internally spaced at 1.1 x 63 = 69.3 GHz. Total occupied spectrum: 69.3 + 2 x 69.3 = 207.9 GHz (center-to-center of outer subcarriers plus one signal bandwidth). Allocate a single 212.5 GHz flex-grid slot. Net spectral efficiency: 1200 / 212.5 = 5.65 b/s/Hz.

Result: The superchannel saves 42.5 GHz (17% reduction), improving spectral efficiency from 4.71 to 5.65 b/s/Hz, a 20% improvement. Over a full C-band, this translates to approximately 2-3 additional 400G-equivalent channels.

The trade-off is flexibility. Individually routed channels can be independently dropped and added at intermediate nodes, while superchannel subcarriers must all follow the same path. For backbone links where traffic typically transits without intermediate add/drop, superchannels offer significant guard band savings. For metro and regional networks with frequent add/drop, individually routed channels provide operational flexibility at the cost of spectral efficiency.

Submarine cable systems take this optimization to its extreme. Modern submarine SLTE (Submarine Line Terminal Equipment) uses a gridless architecture with no guard band between channels. Channel spacing is driven solely by the baud rate and laser frequency stability: typically 140-150 GHz for baud rates of 140 Gbaud. The absence of intermediate WSS filtering in the submarine segment eliminates the WSS guard band entirely, with ROADM-based add/drop only occurring at branching units where WSS filtering creates guard bands of 10-20 GHz at the boundaries between traffic bands directed to different destinations.

6.3 Spectrum Defragmentation

Over time, as channels are provisioned and deprovisioned in a flex-grid network, spectral fragmentation can occur: small, non-contiguous spectral gaps that are individually too narrow to accommodate new channels but collectively represent significant wasted bandwidth. These fragments are essentially forced guard bands that serve no useful purpose.

Spectrum defragmentation techniques aim to consolidate these fragments by retuning the central frequencies of established connections. Three main approaches exist. Push-pull defragmentation shifts existing channels toward one end of the spectrum without traffic disruption. Make-before-break defragmentation provisions a new path before tearing down the old one, requiring spare transponder resources. Hitless defragmentation coordinates the TX laser frequency shift with the RX tracking to move channels without bit errors.

The guard band design directly affects fragmentation severity. With 12.5 GHz slot width granularity, the average wasted guard band per channel is 6.25 GHz (half the granularity). For a fiber with 60 channels, this represents approximately 375 GHz of excess guard band, nearly enough for five additional 75 GHz channels. Reducing the slot width granularity to 6.25 GHz (if WSS technology supports it) would halve this fragmentation loss.

7. Real-World Design Examples and Case Studies

7.1 Guard Band Design for 400G/800G Coherent Systems

Modern coherent transponders such as the AX1200 module family provide extensive flexibility in baud rate and bandwidth selection, enabling network designers to optimize guard bands for specific deployment scenarios. The following analysis uses actual transponder specifications to demonstrate practical guard band design.

| Line Rate | BW (GHz) | Baud Rate | b/s (approx) | OSNR-ZR (dB) | Occupied BW (GHz) | Guard Band (GHz) | GB % | Max CD (ps/nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400G | 75 | 63 | 3.97 | 19.8 | 69.3 | 5.7 | 7.6% | -50,000 |

| 400G | 100 | 88 | 2.84 | 18.4 | 96.8 | 3.2 | 3.2% | -70,000 |

| 400G | 137.5 | 125 | 2.0 | 17.4 | 137.5 | 0 | 0% | -100,000 |

| 600G | 100 | 88 | 4.26 | 23.2 | 96.8 | 3.2 | 3.2% | -15,000 |

| 800G | 137.5 | 125 | 4.0 | 23.6 | 137.5 | 0 | 0% | -50,000 |

| 800G | 150 | 138 | 3.62 | 23.3 | 151.8 | ~0 | ~0% | -50,000 |

| 1000G | 137.5 | 125 | 5.0 | 27.6 | 137.5 | 0 | 0% | -15,000 |

| 1200G | 150 | 138 | 5.43 | 31.3 | 151.8 | ~0 | ~0% | -10,000 |

Several design patterns emerge from this data. For long-haul deployments (distances greater than 2000 km requiring CD tolerance of 50,000 ps/nm or more), the 400G at 75 GHz configuration offers the best balance of spectral efficiency (5.33 b/s/Hz), reasonable OSNR requirement (19.8 dB), and high CD tolerance. Its 7.6% guard band overhead provides comfortable margin for laser drift and cascaded ROADM filtering.

For metro and DCI deployments where distances are short and OSNR margins are generous, the 800G at 137.5 GHz or even 1200G at 150 GHz configurations maximize capacity per fiber. These configurations operate at near-zero guard band, requiring precise laser frequency control and minimal ROADM cascades. The 800G/137.5 GHz configuration at 4.0 bits/symbol achieves essentially Nyquist-limited spectral efficiency with a manageable 23.6 dB OSNR requirement.

The choice between a narrower bandwidth configuration (higher bits/symbol, higher OSNR, shorter reach) and a wider bandwidth configuration (lower bits/symbol, lower OSNR, longer reach) is fundamentally a guard band trade-off: narrower bandwidth means less guard band waste but less reach margin.

7.2 C+L Band Guard Band Between Bands

When expanding from C-band to C+L band operation, a guard band must be allocated between the two bands to accommodate the band-splitting filter. The C-band extends from approximately 191.3 to 196.1 THz (1528-1568 nm), and the L-band from approximately 186.1 to 190.9 THz (1570-1612 nm). The gap between the C-band lower edge and L-band upper edge is approximately 400 GHz (about 3 nm).

In practice, the inter-band guard band needs to account for the roll-off of the C/L band splitter filter, the gain profile edges of the C-band and L-band EDFAs, and any transition channels that suffer from degraded EDFA gain at the band edges. Typical inter-band guard bands range from 200 to 500 GHz depending on the EDFA technology and filter design. This guard band represents approximately 2-5% of the total C+L spectrum, a relatively small overhead for the benefit of approximately doubling the available spectrum.

The L-band EDFA gain profile is generally less flat than the C-band, particularly at the band edges, which may require wider guard bands at the L-band edges or the use of gain-equalization filters. The AC1200 L-band module specifies a transmitter frequency range of 186.10 to 190.85 THz on a 6.25 GHz grid, confirming the usable L-band spectrum.

7.3 Submarine Cable Guard Band Elimination

Modern submarine cable systems represent the state of the art in guard band minimization. The submarine SLTE offers a gridless architecture with no guard band between channels within a traffic band. There is total freedom in WDM channel selection and spacing, limited only by the baud rate and laser frequency stability. For 140 Gbaud transponders, the minimum channel spacing is approximately 140-150 GHz, essentially at the Nyquist limit.

This is possible because submarine systems have unique characteristics that relax guard band requirements. The optical path is point-to-point (or point-to-branching-unit) without intermediate ROADM nodes, eliminating cascaded filtering penalties within the trunk. The submerged amplifiers use simple EDFA chains without WSS filtering. When ROADMs are used at branching units, the WSS-induced guard band (10-20 GHz) appears only at the boundaries between traffic bands directed to different branch destinations.

The guard band savings are substantial. A submarine system with 40 nm of C-band spectrum (~5 THz at 1550 nm) carrying 32 channels at 140 Gbaud with zero inter-channel guard band achieves approximately 20 Tb/s per fiber pair. The same spectrum with 50 GHz fixed-grid spacing would support only ~100 channels of 100G (10 Tb/s), or ~66 channels of 200G (13.2 Tb/s), demonstrating that gridless operation can improve capacity by 50% or more compared to legacy fixed-grid approaches.

8. Advanced Topics: Nyquist and Super-Nyquist Guard Band Reduction

The ultimate frontier of guard band optimization is the elimination of guard bands entirely, operating at or below the Nyquist frequency spacing limit.

Ideal Nyquist WDM (Δf = Rs): When channel spacing equals the symbol rate exactly, the guard band is zero. This requires perfectly rectangular channel spectra (sinc pulses in the time domain), which are theoretically achievable but impractical because sinc pulses have infinite duration and slow decay. In practice, the closest approach uses very low roll-off factors (ρ = 0.01-0.05) with digital pulse shaping, achieving channel spacings of 1.01-1.05 x Rs with minimal penalty.

Quasi-Nyquist WDM (1.0 < Δf/Rs < 1.2): This is the operating regime of most modern coherent systems. With SRRC ρ = 0.1, the occupied bandwidth extends to 1.1 x Rs, and channel spacing at or slightly above this value provides near-zero crosstalk. The guard band per channel pair is 0 to 0.2 x Rs, representing a spectral overhead of 0-17%.

Super-Nyquist WDM (Δf < Rs): By intentionally allowing spectral overlap between channels, super-Nyquist WDM achieves negative guard bands, where the channel spacing is less than the signal bandwidth. This requires specialized DSP at the receiver to cancel the induced inter-channel interference. Experimental demonstrations have achieved 110 Gbaud PDM-QPSK at 100 GHz spacing (δf = 0.91), with acceptable penalty after multi-modulus equalization and MLSE processing. The 3 dB bandwidth of the super-Nyquist 9QAM-like signal is less than 0.5 x baud rate, enabling extreme spectral compression.

Figure 6: Evolution of WDM channel spacing regimes — from conventional WDM with large guard bands to super-Nyquist WDM with intentional spectral overlap. The transition is enabled by coherent detection, DSP, and digital pulse shaping.

Super-Nyquist signals are generated by cascading a quadrature duobinary (QDB) filter with the standard SRRC filter. The QDB filter has the transfer function HQDB(z) = 1 + z-1, which converts a QPSK signal into a 9QAM-like constellation while significantly suppressing spectral side lobes. The resulting signal has inherently good tolerance to cascaded narrow-band filtering: experimental data shows that 110 Gbaud super-Nyquist signals maintain BER below the 7% HD-FEC threshold even after 10 cascaded ROADMs that narrow the effective bandwidth from 94.8 GHz to 84.5 GHz.

The practical adoption of super-Nyquist techniques in commercial systems is currently limited by the DSP complexity required for inter-channel interference cancellation. However, as DSP ASIC capabilities continue to advance following Moore's Law, super-Nyquist operation may become commercially viable for high-capacity backbone links where every gigahertz of spectral efficiency matters.

| Regime | Δf / Rs | Guard Band | Crosstalk | DSP Complexity | Commercial Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard WDM | > 1.5 | Large (>50%) | None | Low | Legacy systems |

| Quasi-Nyquist | 1.05 - 1.2 | Small (5-17%) | Minimal | Moderate | Widely deployed |

| Ideal Nyquist | 1.0 | Zero | Zero (ideal) | Moderate-High | Emerging |

| Super-Nyquist | < 1.0 | Negative (overlap) | Controlled | High | Research/Lab |

9. Future Directions

Several technology trends are driving further guard band optimization in optical networks.

Finer grid granularity: As WSS technology improves, sub-12.5 GHz slot width granularity (potentially 6.25 GHz steps) will reduce the quantization overhead in flex-grid systems. This is particularly valuable for high-baud-rate systems where the current 12.5 GHz granularity creates relatively large percentage overhead on signals occupying 100+ GHz.

AI/ML-based optimization: Machine learning approaches to RMLSA can optimize guard band allocation dynamically based on real-time network monitoring data, including actual OSNR margins, filter shapes, and laser drift measurements. Rather than using worst-case guard band budgets, AI systems can operate with tighter margins when conditions allow, reclaiming spectrum that would otherwise be wasted.

Probabilistic constellation shaping (PCS): PCS enables fine-grained control over the spectral efficiency versus reach trade-off. By adjusting the probability distribution of constellation points, PCS can operate at fractional bits-per-symbol values (e.g., 3.5 b/s instead of 4.0 for 16QAM or 3.0 for 8QAM), allowing more precise matching of the signal to the available guard band and OSNR conditions.

Space-Division Multiplexing (SDM): Multi-core and few-mode fibers introduce a spatial dimension to guard band optimization. In spectrally-spatially flexible optical networks (SS-FONs), guard bands between superchannels can be optimized across both spectral and spatial domains, potentially reducing the total guard band overhead per unit of transported capacity.

Dynamic guard band adjustment: Future software-defined optical networks may support real-time guard band adjustment, where channels dynamically retune their TX laser frequencies and spectral shaping to compensate for measured soft failures such as laser drift, filter misalignment, or wavelength-dependent performance variations. Feedback-based channel frequency optimization can maximize total capacity or minimum subchannel quality of transmission (QoT) performance during network operation.

10. Conclusion

Guard band optimization is a critical discipline in modern optical network design, directly impacting fiber capacity, spectral efficiency, and network economics. The evolution from fixed 100 GHz grids with 50%+ guard band overhead to today's flex-grid and gridless architectures with near-zero guard bands represents one of the most significant capacity improvements in optical networking history.

The key design principles for guard band optimization can be summarized. First, the minimum theoretical guard band is determined by the roll-off factor of the pulse-shaping filter, with GBmin = Rs x ρ. For a typical roll-off of 0.1, this is just 10% of the symbol rate. Second, practical systems must add margin for laser frequency uncertainty (approximately 3 GHz), WSS filter transition bands (10-20 GHz at port boundaries), and cascaded filter narrowing (1-1.5 GHz per ROADM). Third, higher-order modulation formats require proportionally wider guard bands due to increased crosstalk sensitivity, but this is more than offset by their improved spectral efficiency. Fourth, superchannel architectures eliminate WSS guard bands between internally routed subcarriers, achieving 15-20% capacity improvements over individually routed channels. Fifth, submarine and gridless systems demonstrate that near-zero guard band operation is achievable when intermediate WSS filtering is absent.

As the industry pushes toward 800G, 1.2T, and beyond, guard band optimization remains an essential tool for maximizing the return on deployed fiber infrastructure. The combination of advanced DSP, flex-grid ROADMs, and intelligent network planning will continue to push spectral efficiency closer to the physical limits.

References

[1] ITU-T Recommendation G.694.1 - Spectral grids for WDM applications: DWDM frequency grid.

[2] ITU-T Recommendation G.709 - Interfaces for the optical transport network.

[3] J. Yu and N. Chi, "Digital Signal Processing In High-Speed Optical Fiber Communication: Principle and Application," Tsinghua University Press / Springer.

[4] R. Essiambre et al., "Capacity Limits of Optical Fiber Networks," J. Lightwave Technol.

[5] M. Jinno et al., "Elastic and adaptive optical networks: Possible adoption scenarios and future standardization aspects," IEEE Commun. Mag.

[6] OIF Implementation Agreement for Flex-Grid Networking.

[7] RFC 7699 - Generalized Labels for the Flexi-Grid in Lambda Switch Capable (LSC) Label Switching Routers.

[8] Sanjay Yadav, "Optical Network Communications: An Engineer's Perspective" - Bridge the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Optical Networking.

Developed by MapYourTech Team

For educational purposes in Optical Networking Communications Technologies

Note: This guide is based on industry standards, best practices, and real-world implementation experiences. Specific implementations may vary based on equipment vendors, network topology, and regulatory requirements. Always consult with qualified network engineers and follow vendor documentation for actual deployments.

Feedback Welcome: If you have any suggestions, corrections, or improvements to propose, please feel free to write to us at feedback@mapyourtech.com

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here