20 min read

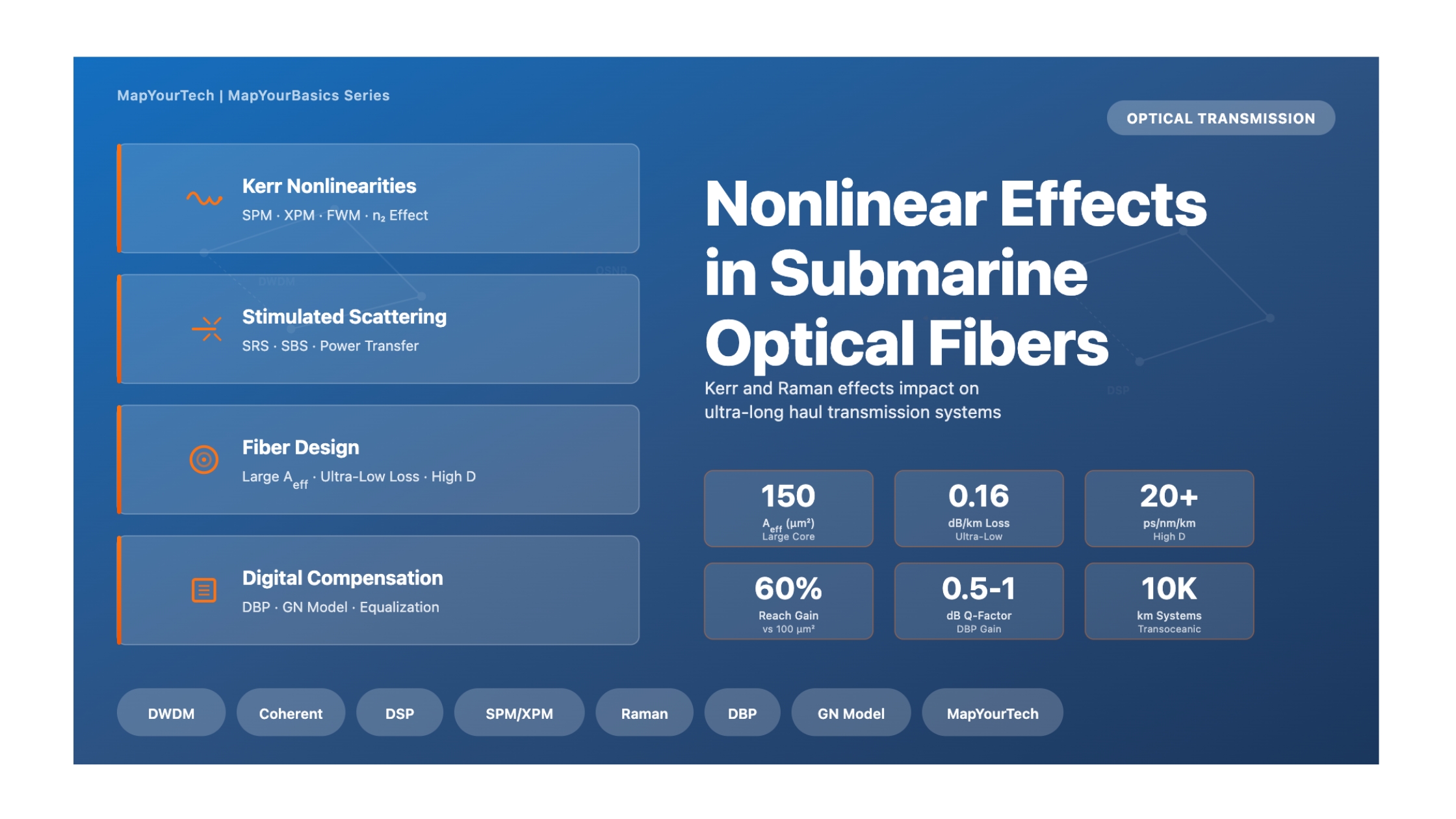

Nonlinear Effects in Submarine Optical Fibers

Understanding Kerr and Raman nonlinearities and their impact on ultra-long haul transmission performance

Introduction

Nonlinear effects in optical fibers represent one of the fundamental limitations to achieving maximum capacity and reach in submarine cable systems. While linear impairments such as fiber attenuation and chromatic dispersion can be effectively managed through optical amplification and digital signal processing, nonlinear effects impose a more complex challenge. These phenomena arise from the interaction between high-intensity optical signals and the silica glass medium, fundamentally altering the refractive index of the fiber and causing signal distortions that accumulate over thousands of kilometers.

In modern submarine systems transmitting over transoceanic distances exceeding 10,000 km, the interplay between optical power, chromatic dispersion, and fiber nonlinearity creates a delicate balance. System designers must navigate a power optimization regime where increasing launch power improves optical signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR) but simultaneously exacerbates nonlinear distortions. Understanding these effects is essential for achieving the multi-terabit capacities demanded by contemporary submarine networks.

Critical Design Challenge: Submarine systems operate in a nonlinear regime where the optimal launch power represents a trade-off between amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) noise degradation at low powers and nonlinear distortion accumulation at high powers. This optimization point typically occurs when ASE noise equals approximately twice the nonlinear interference.

Fundamental Principles

Nonlinear effects in optical fibers stem from two fundamental physical mechanisms: the Kerr effect and stimulated scattering processes. These phenomena become significant when light intensity reaches levels where the optical properties of the medium begin to depend on the signal power itself.

The Kerr Nonlinearity

The Kerr effect describes the intensity-dependent refractive index of silica glass. The fiber refractive index can be expressed as a function of optical intensity, where the refractive index increases linearly with optical power. This relationship is characterized by the nonlinear index coefficient, which for pure silica has a value of approximately 2.7 × 10⁻²⁰ m²/W.

Figure 1: The Kerr effect causes the fiber refractive index to vary with signal intensity, leading to multiple nonlinear phenomena including SPM, XPM, and FWM.

n = n₀ + n₂(P/Aeff)

where:

n = total refractive index

n₀ = linear refractive index

n₂ = nonlinear index coefficient (2.7 × 10⁻²⁰ m²/W for silica)

P = optical power

Aeff = effective area of fiber core

Although the nonlinear coefficient is extremely small, its effects accumulate significantly over the multi-thousand kilometer transmission distances typical of submarine systems. The confined optical power within the small fiber core (characterized by effective area Aeff typically ranging from 80 to 150 μm²) combined with moderate launch powers of approximately 0 dBm per channel creates sufficient intensity to produce measurable nonlinear distortions.

Stimulated Raman Scattering

Stimulated Raman scattering represents an inelastic scattering process where pump photons interact with optical phonons in the silica glass structure, transferring energy to signal photons at longer wavelengths. This effect exhibits a peak gain at a frequency shift of approximately 13.2 THz below the pump wavelength, corresponding to roughly 100 nm in the C-band.

In wideband wavelength division multiplexed (WDM) systems, Raman scattering causes power transfer from shorter wavelength channels to longer wavelength channels. This interchannel power crosstalk creates a spectral tilt across the multiplex that must be compensated through gain flattening filters in optical amplifiers. The Raman gain coefficient depends on the fiber effective area and the Germanium doping concentration in the core.

System Model and Propagation Equations

Nonlinear impairments in submarine optical fibers can be systematically categorized based on their physical origin and the number of channels involved in the interaction. Understanding this classification is essential for developing appropriate mitigation strategies.

Figure 2: Hierarchical classification of nonlinear effects showing Kerr-based phenomena (SPM, XPM, FWM) and stimulated scattering processes (SRS, SBS) with their characteristic impacts on submarine transmission systems.

| Category | Effect | Description | Primary Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kerr Effects (Intrachannel) | Self-Phase Modulation (SPM) | Power-dependent phase shift within a single channel | Pulse distortion, spectral broadening |

| Cross-Phase Modulation (XPM) | Power fluctuations in one channel induce phase changes in adjacent channels | Pattern-dependent phase noise | |

| Four-Wave Mixing (FWM) | Interaction of three waves generates new frequencies through third-order intermodulation | Interchannel crosstalk, power depletion | |

| Stimulated Scattering | Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) | Power transfer from short to long wavelengths via inelastic photon scattering | Spectral power tilt, dynamic crosstalk |

| Stimulated Brillouin Scattering (SBS) | Backward scattering through acoustic phonon interaction | Launch power limitation, back-reflection |

Self-Phase Modulation

Self-phase modulation occurs when the intensity variations of a signal induce time-dependent phase shifts on itself through the Kerr effect. In pre-coherent systems with periodic dispersion compensation, SPM manifested as pulse distortion that preserved the signal waveform within each span. However, in modern uncompensated coherent systems where dispersion accumulates to values exceeding 200,000 ps/nm, the signal waveform experiences significant temporal broadening span after span.

The accumulated nonlinear phase shift caused by SPM interacts with chromatic dispersion to create intrachannel nonlinear distortions. This interaction can be understood through the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, which governs signal evolution along the fiber and includes both dispersive and nonlinear terms. The strength of SPM depends on the fiber nonlinear coefficient γ, which is inversely proportional to the effective area.

Cross-Phase Modulation and Four-Wave Mixing

In WDM systems, the Kerr nonlinearity enables interactions between different wavelength channels. Cross-phase modulation converts intensity fluctuations in one channel into phase fluctuations in adjacent channels. The effectiveness of XPM depends critically on the chromatic dispersion of the fiber, which determines the walk-off between channels operating at different wavelengths.

When chromatic dispersion is large, different wavelength channels propagate at different group velocities, creating substantial walk-off that averages out XPM-induced phase noise. Conversely, in systems with tight dispersion management or near the zero-dispersion wavelength, channels remain phase-matched over long distances, making XPM interactions more deterministic and pattern-dependent.

Four-wave mixing represents a parametric process where three optical waves interact to generate a fourth wave at a new frequency. The phase-matching condition for FWM depends strongly on chromatic dispersion. In systems with large dispersion, the phase mismatch between interacting waves suppresses FWM efficiency, making this effect negligible in modern uncompensated submarine systems utilizing high-dispersion fibers.

Stimulated Raman Scattering in WDM Systems

The impact of stimulated Raman scattering in submarine systems manifests as both static and dynamic power crosstalk between WDM channels. The static component creates a predictable spectral tilt that can be compensated using gain-flattening filters within each repeater. The dynamic component, which varies with the transmitted data patterns, becomes less significant as the number of wavelength channels increases or when fiber chromatic dispersion is enhanced.

In ultra-wideband systems spanning more than 25 nm of optical bandwidth, the cumulative Raman tilt over 10,000 km transmission distances can exceed several decibels. This necessitates careful power management and periodic equalization to maintain acceptable OSNR uniformity across all channels.

Dispersion-Nonlinearity Interplay: The effectiveness of chromatic dispersion in mitigating interchannel nonlinear effects explains why modern submarine systems employ fibers with large dispersion values (greater than 20 ps/nm/km) despite the availability of dispersion-shifted fibers. Large dispersion creates walk-off that reduces pattern-dependent distortions from XPM and suppresses FWM generation.

Gaussian Noise Model for Nonlinear Interference

A significant breakthrough in understanding nonlinear propagation came with the development of the Gaussian noise (GN) model in 2010-2011. Research groups demonstrated that after propagation through uncompensated fiber systems, the nonlinear distortions exhibit a Gaussian statistical distribution. This insight enabled a simplified analytical framework for system design that treats nonlinear interference as additive white Gaussian noise.

The GN model allows engineers to extend the classical OSNR formulation by introducing a nonlinear interference term alongside the ASE noise contribution. The total system performance can be characterized by a generalized signal-to-noise ratio that accounts for both linear and nonlinear noise sources.

Figure 3: System Q-factor versus launch power showing the trade-off between ASE noise and nonlinear interference. The optimum operating point occurs where ASE noise equals approximately 2× the nonlinear interference power.

1/OSNRtotal = 1/OSNRASE + 1/OSNRNLI

where:

OSNRASE = signal-to-noise ratio from amplified spontaneous emission

OSNRNLI = signal-to-noise ratio from nonlinear interference

SNRNLI ∝ 1/(N·Pch²)

N = number of spans

Pch = launch power per channel

The GN model reveals that nonlinear interference power scales with the square of the channel launch power and linearly with the number of amplified spans. This quadratic dependence on power explains why increasing launch power beyond a certain optimum point degrades system performance. The optimum operating point occurs when ASE noise equals approximately twice the nonlinear interference power.

Impact of Fiber Parameters

The GN model provides valuable scaling rules for understanding how fiber characteristics influence nonlinear performance. For a given repeater configuration and ideal Nyquist signaling, the maximum achievable transmission reach scales with fiber effective area and chromatic dispersion according to a specific relationship.

Consider a reference system with 18 ps/nm/km dispersion and 100 μm² effective area. Increasing the effective area to 200 μm² could improve reach by approximately 60 percent, while increasing dispersion to 25 ps/nm/km would yield only an 11 percent reach improvement. This analysis clearly demonstrates that increasing effective area represents the most efficient approach to reducing nonlinear penalties and extending both reach and spectral efficiency.

Fiber Design for Nonlinearity Mitigation

Modern submarine fiber design focuses on three key parameters to minimize nonlinear impairments while maintaining acceptable bend loss and single-mode operation: effective area, attenuation, and chromatic dispersion. The optimization of these parameters has evolved significantly over the past two decades.

Figure 4: Evolution of submarine fiber parameters showing continuous improvement in effective area and attenuation reduction, enabling higher capacities and longer reaches in modern submarine systems.

Large Effective Area Fibers

The effective area of a fiber quantifies how the optical power spreads across the core cross-section. Larger effective areas reduce the optical intensity for a given power level, thereby diminishing nonlinear interactions. Early submarine systems employed standard single-mode fibers with effective areas around 80 μm². Modern ultra-long haul systems utilize fibers with effective areas reaching 150 μm² or larger.

Increasing effective area requires careful refractive index profile design to maintain single-mode operation and acceptable macrobending loss. Pure silica core fibers (PSCF) offer an additional advantage beyond large effective area: the nonlinear coefficient n₂ of pure silica is typically 5 to 10 percent lower than Germanium-doped cores with equivalent dimensions. This inherent material property provides further nonlinearity mitigation.

Ultra-Low Loss Fibers

Fiber attenuation fundamentally limits transmission reach by degrading OSNR. Modern submarine fibers achieve attenuation values as low as 0.16 dB/km at 1550 nm through meticulous control of manufacturing processes. Recent research has demonstrated record low attenuation of 0.146 dB/km, approaching the theoretical Rayleigh scattering limit of silica glass.

The relationship between attenuation and nonlinear performance is subtle but important. Lower attenuation permits longer span lengths between repeaters for the same accumulated loss, which increases the effective interaction length for Raman amplification if employed. Additionally, reducing attenuation allows operation at lower launch powers while maintaining the same OSNR margin, thereby reducing nonlinear accumulation.

Dispersion Management Evolution

The approach to chromatic dispersion management in submarine systems has undergone fundamental transformation with the adoption of digital coherent transmission. Pre-coherent systems required careful dispersion compensation to maintain acceptable pulse broadening. Multiple dispersion management strategies were developed, including dispersion-shifted fibers with near-zero dispersion, non-zero dispersion-shifted fibers, and hybrid dispersion-managed fiber schemes combining positive and negative dispersion fiber types.

The introduction of coherent detection after 2008 eliminated the need for optical dispersion compensation, as digital signal processing in the receiver can effectively compensate any accumulated dispersion value. Modern submarine systems employ large effective area fibers with positive dispersion around 20 ps/nm/km. The accumulated dispersion over transoceanic distances can exceed 200,000 ps/nm, with full compensation achieved through digital processing at the receiver.

This shift to uncompensated transmission with large dispersion provides significant nonlinearity mitigation benefits. The large local dispersion creates substantial walk-off between WDM channels, reducing XPM pattern dependence and suppressing FWM. Additionally, intrachannel nonlinear interactions are mitigated as the signal experiences rapid temporal broadening span after span.

Power Optimization and System Operating Point

The fundamental challenge in submarine system design lies in determining the optimal launch power per channel. This optimization balances two competing effects: ASE noise degradation at low powers and nonlinear interference accumulation at high powers.

At low launch powers, the signal OSNR degrades due to insufficient signal power relative to the ASE noise generated by the cascade of optical amplifiers. As launch power increases, OSNR improves linearly with power. However, nonlinear interference grows with the square of the launch power, eventually dominating the impairment budget.

The optimum launch power occurs at the intersection of these two regimes, where the marginal improvement in ASE-limited OSNR equals the marginal degradation from increased nonlinear interference. For typical submarine system parameters, this optimum typically occurs when ASE noise power equals approximately twice the nonlinear interference power, corresponding to a system operating point where linear and nonlinear contributions to signal degradation are balanced.

Propagation Impairment: Laboratory transmission experiments over 10,000 km typically measure propagation impairments from nonlinear effects in the range of 1 to 2 dB. This represents the difference between the measured Q factor and the theoretical OSNR-based Q factor, quantifying the penalty specifically attributable to the interplay between chromatic dispersion and nonlinear effects.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite significant advances in understanding and managing nonlinear effects, several fundamental limitations persist in submarine optical transmission systems.

Capacity-Distance Trade-off

Nonlinear effects impose a fundamental limit on the capacity-distance product achievable in submarine systems. As transmission distance increases, the accumulated nonlinear interference grows, forcing operation at lower launch powers to maintain acceptable signal quality. This power reduction degrades OSNR, ultimately limiting the supportable modulation format complexity and spectral efficiency.

For ultra-long haul systems exceeding 10,000 km, designers must carefully select modulation formats that can operate at the available OSNR while providing sufficient capacity. Higher-order modulation formats such as 16-QAM or 32-QAM offer greater spectral efficiency but require higher OSNR margins, making them viable only for moderate distances or when operated with lower spectral density.

Interchannel Nonlinear Interactions

While intrachannel nonlinear effects can be partially compensated through digital signal processing techniques such as digital back propagation, interchannel effects present more significant challenges. Cross-phase modulation and four-wave mixing depend on the data patterns transmitted in all WDM channels simultaneously, requiring knowledge of all channel waveforms for effective compensation.

Practical limitations make interchannel nonlinearity compensation difficult to implement. The digital signal processor for each channel would need to receive digitized waveforms from all neighboring channels, requiring substantial bandwidth for inter-channel communication. Additionally, in systems with optical add-drop multiplexers, channels may not propagate together over the entire transmission path, invalidating assumptions required for compensation algorithms.

Temperature and Aging Effects

The nonlinear coefficient of optical fibers exhibits weak temperature dependence, and submarine cables experience temperature variations over seasonal and geographic scales. While these variations are generally small, they can contribute to long-term performance fluctuations that must be accommodated in system margin calculations.

Fiber aging and the evolution of fiber characteristics over the multi-decade lifetime of submarine systems represent another concern. Hydrogen absorption can gradually increase fiber attenuation, requiring operation at higher launch powers and potentially exacerbating nonlinear effects. System designs must incorporate sufficient margin to account for these long-term degradation mechanisms.

Practical Mitigation Approaches

Modern submarine systems employ multiple complementary strategies to mitigate nonlinear impairments and maximize transmission performance.

Digital Back Propagation

Digital back propagation (DBP) represents the most powerful digital signal processing technique for compensating deterministic nonlinear distortions. The fundamental concept involves numerically solving the inverse propagation equation in the receiver digital signal processor, effectively undoing the combined effects of chromatic dispersion and self-phase modulation that accumulated during transmission.

Figure 5: Digital back propagation reverses the effects of chromatic dispersion and nonlinearity by numerically solving the inverse propagation equation in the DSP, recovering the original transmitted signal with typical improvements of 0.5-1 dB in Q-factor.

The implementation of DBP requires solving the backward-propagating nonlinear Schrödinger equation using numerical methods such as the split-step Fourier method. The received optical waveform serves as the initial condition, and the algorithm propagates this signal backwards through a virtual fiber with opposite signs for attenuation, dispersion, and nonlinearity parameters.

Experimental demonstrations of DBP in submarine transmission scenarios have achieved performance improvements of 0.5 to 1 dB in Q factor for transoceanic distances. These gains translate directly to increased system margin that can be allocated toward higher capacity, extended reach, or reduced operational expenses through lower launch power requirements.

Several practical considerations affect DBP implementation complexity. The algorithm must track variations in fiber type and dispersion along the submarine cable, though equivalent link techniques can reduce computational burden by approximating the actual dispersion map. Additionally, the step size used in the split-step Fourier method directly impacts both compensation effectiveness and processing complexity, requiring careful optimization.

Optical Phase Conjugation

Mid-span spectral inversion through optical phase conjugation offers an alternative approach to nonlinearity compensation in the optical domain. This technique relies on the principle that reversing the sign of the optical field at the midpoint of a symmetric transmission link causes the second half of the link to undo the nonlinear distortions accumulated in the first half.

While elegant in concept, optical phase conjugation faces practical limitations that have prevented widespread deployment. The technique requires symmetric power evolution along the entire transmission path, necessitating careful dispersion and power management. Additionally, interchannel effects remain incompletely compensated unless all WDM channels are conjugated simultaneously. The emergence of powerful digital coherent receivers has made digital phase conjugation approaches more practical than all-optical implementations.

Advanced Modulation and Coding

Sophisticated modulation formats and forward error correction codes provide another avenue for improving nonlinear tolerance. Probabilistic constellation shaping optimizes the signal distribution to better match the characteristics of the nonlinear fiber channel. Time-domain and polarization-domain interleaving techniques can reduce pattern dependencies in nonlinear interactions.

Modern submarine systems employ rate-adaptive transmission, where the modulation format and coding overhead are optimized for each specific route based on distance, fiber characteristics, and required capacity. This flexibility enables efficient use of available system margin while maintaining acceptable quality of transmission across diverse deployment scenarios.

System-Level Optimization

Beyond fiber and signal processing innovations, system-level design choices significantly impact nonlinear performance. Optimizing span lengths, repeater spacing, and amplifier characteristics can improve the balance between linear and nonlinear impairments. Hybrid Raman-EDFA amplification architectures provide distributed gain that reduces peak power excursions within each span.

Spectral power shaping across the WDM multiplex can mitigate Raman tilt effects. Pre-emphasis at the transmitter compensates for predictable spectral variations, while adaptive power management adjusts channel powers based on real-time performance monitoring. These techniques enable more uniform OSNR distribution across all wavelength channels, maximizing overall system capacity.

Key System Design Principles

- Nonlinear interference scales quadratically with launch power, creating an optimum operating point where ASE noise equals approximately 2× nonlinear interference power

- Large effective area fibers (greater than 110 μm²) provide the most effective mitigation of Kerr nonlinearities, offering superior performance compared to dispersion increases

- High chromatic dispersion (greater than 20 ps/nm/km) in uncompensated systems creates beneficial channel walk-off that reduces interchannel nonlinear interactions

- Ultra-low loss fibers (less than 0.17 dB/km) enable longer reach and higher capacity by improving OSNR margin and reducing required launch powers

- Digital back propagation can recover 0.5 to 1 dB of performance degradation from intrachannel nonlinear effects in long-haul systems

- The Gaussian noise model provides an accurate analytical framework for predicting nonlinear interference in modern uncompensated coherent systems

- Pure silica core fibers offer inherently lower nonlinear coefficients compared to Germanium-doped alternatives while supporting large effective areas

Conclusion

Nonlinear effects in submarine optical fibers represent a fundamental physical limitation that shapes the design and performance of transoceanic transmission systems. The complex interplay between Kerr nonlinearities, stimulated scattering processes, chromatic dispersion, and optical amplifier noise creates a challenging optimization space that requires careful consideration of multiple interacting factors.

Modern submarine systems have achieved remarkable capacity and reach through the intelligent combination of advanced fiber designs, sophisticated digital signal processing, and optimized system architectures. Large effective area ultra-low loss fibers minimize nonlinear accumulation while maximizing OSNR. High chromatic dispersion mitigates interchannel effects without penalty in coherent systems. Digital back propagation partially compensates deterministic nonlinear distortions at the receiver.

Looking forward, continued innovation in nonlinearity management will be essential for meeting growing bandwidth demands across submarine routes. Emerging technologies such as spatial division multiplexing with multi-core or multi-mode fibers may provide additional degrees of freedom for reducing nonlinear interactions. Advanced machine learning techniques could optimize constellation shaping and power allocation in ways that classical approaches cannot achieve. The fundamental physics of nonlinear propagation will continue to challenge and inspire engineers working to push the boundaries of submarine optical transmission.

The journey from understanding basic Kerr effect physics to deploying multi-terabit submarine systems demonstrates the power of sustained research and development in optical communications. As system capacities continue to grow and distances extend, the principles and techniques for managing nonlinear effects will remain central to enabling global connectivity through undersea fiber optic networks.

References

- ITU-T Recommendation G.977.1, "Architecture of optical submarine networks with optical amplifiers," International Telecommunication Union, 2020.

- ITU-T Recommendation G.978, "Characteristics of optical fibre submarine cables," International Telecommunication Union, 2025.

- Agrawal, G.P., "Nonlinear Fiber Optics," 5th Edition, Academic Press, 2013.

- Poggiolini, P., "The GN Model of Non-Linear Propagation in Uncompensated Coherent Optical Systems," Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 30, no. 24, pp. 3857-3879, 2012.

- Essiambre, R.-J., et al., "Capacity Limits of Optical Fiber Networks," Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 662-701, 2010.

- Charlet, G., "Progress in optical modulation formats for high-bit-rate WDM transmissions," IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 469-483, 2006.

- Mecozzi, A. and Essiambre, R.-J., "Nonlinear Shannon Limit in Pseudolinear Coherent Systems," Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 2011-2024, 2012.

- Bayvel, P., et al., "Maximising the optical network capacity," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, vol. 374, 20140440, 2016.

- Ellis, A.D., et al., "Communication networks beyond the capacity crunch," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, vol. 374, 20150191, 2016.

- Winzer, P.J. and Neilson, D.T., "From Scaling Disparities to Integrated Parallelism: A Decathlon for a Decade," Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 1099-1115, 2017.

- Yadav, Sanjay, "Optical Network Communications: An Engineer's Perspective" – Bridge the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Optical Networking.

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here