29 min read

Submarine vs Terrestrial System Design Differences

Practical Information Based on Industry ExperienceExecutive Summary & Introduction

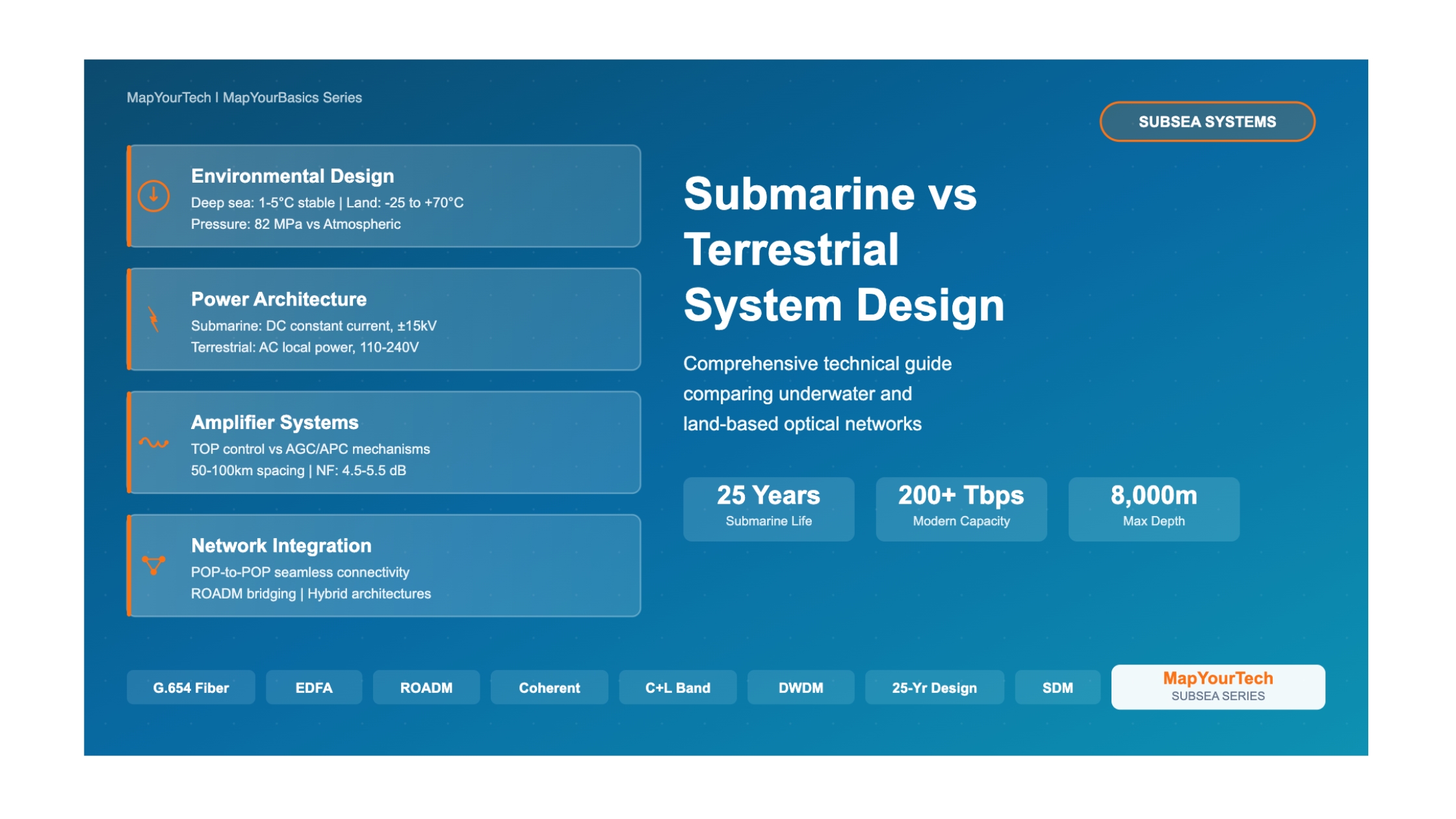

Submarine and terrestrial optical fiber systems represent two fundamentally different engineering approaches to long-distance data transmission. While both utilize fiber optic technology as their core transmission medium, the environmental conditions, operational requirements, reliability standards, and design constraints differ dramatically between undersea and land-based deployments.

Submarine cable systems form the backbone of global internet connectivity, carrying more than 95% of international data traffic across oceans and connecting continents. These remarkable engineering achievements must operate continuously for 25 years in depths reaching 8,000 meters, withstanding pressures of 82.7 MPa (12,000 psi), in constant exposure to seawater at temperatures around 1-5°C in the deep ocean. The inability to easily repair or replace submarine equipment drives unique design philosophies focused on extreme reliability, redundancy, and precise optimization.

In contrast, terrestrial optical systems connect cities, data centers, and network nodes across land, benefiting from relative accessibility for maintenance, flexibility in network topology, and the ability to leverage existing infrastructure. Terrestrial systems face different challenges including wide temperature variations (-25°C to +70°C), physical threats from human activity, and the need for cost-effective scalability across diverse geographic and urban environments.

Why These Differences

Understanding submarine versus terrestrial design differences is critical for optical network professionals because:

Submarine vs Terrestrial Optical Systems: Architectural Overview

Interactive comparison showing key components and environmental differences

Real-World Relevance

As of 2025, there are over 600 active submarine cable systems globally, spanning more than 1.35 million kilometers of ocean floor. The 2Africa cable system, operational in 2024, stretches 45,000 kilometers connecting 34 countries across Africa, Europe, and Asia. Modern submarine systems deliver over 200 Tbps of capacity and continue to evolve with space-division multiplexing (SDM), advanced coherent detection, and C+L band amplification.

The integration of submarine and terrestrial networks has become increasingly important with the trend toward Point-of-Presence (POP) to POP connectivity, where submarine line terminal equipment extends beyond the Cable Landing Station into urban data centers. This hybrid architecture requires careful design to maintain submarine-grade reliability while leveraging terrestrial flexibility.

Recent events, including the 2024 cable cuts in West Africa affecting ten countries, and damage in the Red Sea affecting major telecommunications networks, highlight the critical importance of understanding system vulnerabilities, redundancy strategies, and the distinct repair challenges between submarine and terrestrial segments.

Historical Context & Evolution

The evolution of submarine and terrestrial fiber optic systems represents one of the most remarkable engineering achievements in telecommunications history. While both technologies share common optical principles, their development paths diverged significantly due to fundamentally different operational requirements.

The Optical Era: 1988-2000

The first transatlantic fiber optic cable, TAT-8, became operational in 1988, marking a revolutionary departure from copper-based submarine cables. This 6,700-kilometer system delivered 280 Mbps using 1.3 μm wavelength technology with optical repeaters spaced every 50-70 kilometers. The design life requirement of 25 years immediately established submarine systems as long-term infrastructure investments.

Terrestrial fiber deployment accelerated rapidly during the same period, driven by domestic telecommunication needs and the emerging internet. Unlike submarine systems with their fixed architectures, terrestrial networks benefited from modular designs, allowing incremental capacity additions and technology upgrades without wholesale system replacement.

WDM Revolution: 1995-2005

Wavelength Division Multiplexing (WDM) transformed both submarine and terrestrial systems, but in distinctly different ways. Submarine systems adopted WDM cautiously, with careful optimization of each wavelength channel to maintain the 25-year reliability target. Terrestrial systems embraced rapid WDM expansion, leveraging accessible amplifier sites for quick capacity upgrades.

The telecommunications bubble of 2000-2002 saw massive speculative investments in both domains. When the bubble burst, many submarine cable operators faced bankruptcy due to overcapacity, while terrestrial networks could more easily scale back operations and redeploy capacity to growing markets.

Coherent Revolution: 2010-Present

The introduction of coherent detection and digital signal processing fundamentally changed optical transmission. For submarine systems, coherent technology enabled dramatic capacity increases on existing wet plant infrastructure. Cable systems designed for 100 Gbps per wavelength can now support 400 Gbps or higher through terminal equipment upgrades alone.

Terrestrial coherent systems gained even greater flexibility, with software-definable modulation formats allowing operators to dynamically optimize reach versus capacity based on real-time network conditions. The ability to deploy variable-rate transponders across mixed fiber types became a key terrestrial advantage.

Evolution Timeline: Submarine vs Terrestrial Fiber Systems

Key milestones and technological breakthroughs from 1988 to 2025

Future Outlook: 2025 and Beyond

Both submarine and terrestrial systems are converging toward petabit-scale capacities, but through different technological pathways. Submarine systems are exploring space-division multiplexing with multi-core and multi-mode fibers, while maintaining the wet plant architecture that has proven reliable over decades. Industry leaders predict operational petabit systems crossing the Atlantic Ocean by 2028-2030.

Terrestrial networks are increasingly integrating artificial intelligence for predictive maintenance, dynamic capacity allocation, and automated network optimization. The flexibility of terrestrial infrastructure allows rapid adoption of emerging technologies like hollow-core fiber and semiconductor optical amplifiers.

The trend toward seamless submarine-terrestrial integration continues, with ROADM-based Cable Landing Stations enabling optical bypass directly to Points of Presence, reducing latency and operational costs while blurring the traditional boundaries between the two domains.

Core Concepts & Fundamentals

The fundamental principles of optical fiber transmission apply equally to submarine and terrestrial systems, light propagates through silica fiber via total internal reflection, wavelength division multiplexing enables multiple channels, and optical amplifiers restore signal power. However, the implementation of these principles differs dramatically based on environmental constraints and operational requirements.

Fiber Types and Characteristics

Submarine systems primarily utilize G.654 fiber specifications (particularly G.654.A through G.654.D variants) optimized for ultra-long haul transmission. These fibers feature larger effective areas (typically 110-150 μm²) to reduce nonlinear effects, and are manufactured with extremely low attenuation (≤0.16 dB/km at 1550 nm) with tight tolerance to ensure uniform characteristics across thousands of kilometers.

Terrestrial systems commonly deploy G.652 standard single-mode fiber for metro and regional networks, with G.655 non-zero dispersion-shifted fiber or G.656 for long-haul applications. The accessibility of terrestrial spans allows operators to deploy mixed fiber types and upgrade selectively based on traffic patterns and economics.

Amplification and Repeater Spacing

Submarine repeater spacing is typically optimized between 50-100 kilometers depending on system length, capacity, and fiber type. Shorter systems (under 3,000 km) can use longer spans (~100 km) with higher gain amplifiers. Trans-oceanic systems often utilize 60-80 km spacing to maximize optical signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR) budget across hundreds of repeaters.

Terrestrial amplifier sites offer much greater flexibility, with typical spacing of 80-100 km but the ability to accommodate 40-120 km based on available infrastructure and right-of-way. The key terrestrial advantage is the ability to modify amplifier gain, add inline dispersion compensation, or insert ROADM nodes at any site.

Amplifier Architecture: Submarine vs Terrestrial EDFA Design

Detailed comparison of optical amplifier configurations and control mechanisms

Power Feeding Architecture

Submarine systems require high-voltage DC power feeding from shore-based Power Feeding Equipment (PFE) to energize repeaters along the cable. Operating voltages can reach 15,000 volts for transoceanic systems, with constant current (typically 0.9-1.5 A) regulated to maintain stable amplifier operation. The electrical circuit completes through sea-ground electrodes, with each repeater creating a voltage drop proportional to its power consumption.

Power feeding calculations must account for cable resistance, repeater voltage drops, earth potential differences (particularly at high latitudes where solar activity can induce significant potentials), and repair margin for cable extensions during the system lifetime. Branching units in multi-landing systems include power switching capabilities to reconfigure electrical topology during maintenance operations.

Terrestrial amplifier sites utilize standard AC power infrastructure with local rectification and regulation. This fundamental difference enables terrestrial systems to deploy high-power amplifiers, active cooling, and auxiliary equipment without the severe power constraints inherent to submarine designs.

Environmental Operating Conditions

The deep ocean provides a remarkably stable environment. At depths beyond 1,000 meters, temperature remains constant at 1-5°C year-round, eliminating thermal cycling stress on components. Hydrostatic pressure reaches 82.7 MPa (12,000 psi) at 8,000 meter depths, requiring robust pressure housing but creating consistent external conditions.

Terrestrial equipment must operate across temperature ranges from -25°C to +70°C (and -40°C to +85°C in storage), requiring thermal management, temperature compensation for optical components, and environmental sealing against humidity, dust, and pollutants. Coastal and shallow-water submarine repeaters face an intermediate challenge, experiencing temperature variations from 5°C to 25°C depending on water depth and seasonal thermoclines.

Technical Architecture & Components

The system architecture of submarine and terrestrial networks reflects fundamentally different engineering philosophies. Submarine systems embody a "deploy once, operate forever" approach with fixed wet plant infrastructure designed for 25-year maintenance-free operation. Terrestrial systems embrace modularity and evolutionary upgrades, with accessible amplifier sites enabling technology refresh cycles of 5-10 years.

Submarine System Architecture

A complete submarine cable system comprises the wet plant (submarine cable, repeaters, branching units, and beach manholes) and dry plant (submarine line terminal equipment, power feeding equipment, and network management systems). The wet plant represents the long-term capital investment, while the dry plant can be upgraded to increase capacity without marine operations.

Modern submarine repeaters house multiple amplifier pairs (typically 8-16 fiber pairs per repeater) within beryllium-copper or titanium pressure vessels. Each fiber pair requires bidirectional amplification, achieved through counter-propagating amplifier designs sharing redundant pump lasers for reliability. The repeater housing provides thermal management, dissipating heat through the pressure vessel into the surrounding seawater.

Branching units enable multi-point connectivity without active switching in older passive designs, or with ROADM-based wavelength selective switching in modern systems. ROADM branching units (ROADM-BU) provide bandwidth adaptation, resilience to cable faults through optical bypass, traffic confidentiality through wavelength scrambling, and remote reconfigurability managed through the network management system.

Complete Submarine Cable System Architecture

End-to-end system showing all major components from POP to POP connectivity

Terrestrial System Architecture

Terrestrial optical networks exhibit much greater architectural diversity than submarine systems. Metro networks may utilize ring or mesh topologies with ROADM nodes for wavelength routing. Long-haul terrestrial systems typically follow a linear or hubbed architecture along fiber routes determined by right-of-way availability.

Each terrestrial amplifier site houses equipment in standard telecommunications shelters or huts, with AC power, HVAC cooling, battery backup, and remote monitoring. The ability to access sites enables deployment of additional functionality including optical channel monitors, inline chromatic dispersion compensation modules, wavelength add-drop multiplexers, and optical supervisory channel equipment.

ROADM nodes provide wavelength-level flexibility, enabling dynamic capacity allocation, protection switching, and colorless/directionless add-drop capabilities. Modern terrestrial networks increasingly deploy CDC-F (Colorless, Directionless, Contentionless, and Flexible grid) ROADM architectures based on wavelength selective switches, eliminating pre-planning of wavelength assignments.

Mathematical Models & Formulas

The optical link design for submarine and terrestrial systems relies on the same fundamental equations governing signal propagation, amplified spontaneous emission noise accumulation, and nonlinear impairments. However, the application of these formulas differs significantly due to the contrasting system parameters and constraints.

OSNR Budget Analysis

Optical Signal-to-Noise Ratio represents the primary linear impairment limiting transmission distance. In an amplified optical system, OSNR degrades with each amplification stage due to additive amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) noise. The accumulation differs between submarine and terrestrial implementations.

OSNR = P_signal - P_ASE - 10·log₁₀(B_ref) [dB] Where: P_signal = Signal power at receiver [dBm] P_ASE = Total accumulated ASE noise power [dBm] B_ref = Reference bandwidth (typically 12.5 GHz or 0.1 nm) For N amplifier spans: P_ASE_total = 10·log₁₀(N) + NF + h·ν·B_ref + G Where: N = Number of amplifier spans NF = Noise Figure of each amplifier [dB] G = Gain of each amplifier [dB] h·ν = Photon energy (approximately -58 dBm/Hz at 1550 nm)

For a submarine system with 60 repeaters, each having 5.0 dB noise figure and 20 dB gain, the OSNR at the receiver can be calculated using the standard submarine link formula:

Submarine OSNR Formula (ITU-T standard): OSNR = P_ch - 10·log₁₀(N) - NF + 58 [dB in 0.1 nm] Where: P_ch = Channel power at receiver [dBm] N = Number of amplifiers (repeaters) NF = Noise Figure per amplifier [dB] 58 = Photon energy constant for 1550 nm in 0.1 nm BW For our example (60 repeaters, NF=5.0 dB, P_ch=+3 dBm): OSNR = 3 - 10·log₁₀(60) - 5.0 + 58 = 3 - 17.78 - 5.0 + 58 = 38.2 dB in 0.1 nm Note: This assumes span losses equal repeater gains (transparent system) and neglects ASE loading on amplifier output power.

This simplified formula works because in submarine systems, each span loss is exactly compensated by the corresponding repeater gain, maintaining constant signal power throughout the link. The OSNR degrades only due to accumulating ASE noise from each repeater.

For comparison, the same 6,000 km distance with terrestrial amplifier spacing (80 km) would require 75 amplifiers, yielding OSNR ≈ 36.5 dB with the same NF, demonstrating the OSNR advantage of longer repeater spacing in submarine systems.

Nonlinear Impairments

Fiber nonlinearity becomes significant at the high optical powers used in submarine systems to maximize OSNR. The effective nonlinear coefficient depends on fiber effective area, and the optimal launch power represents a trade-off between linear OSNR degradation and nonlinear penalty accumulation.

φ_NL = γ · P · L_eff [radians] Where: γ = Nonlinear coefficient = 2π·n₂/(λ·A_eff) [1/W/km] P = Optical power [W] L_eff = Effective fiber length = [1 - exp(-α·L)]/α n₂ = Nonlinear refractive index ≈ 2.6×10⁻²⁰ m²/W A_eff = Effective mode area [μm²] α = Fiber attenuation coefficient Submarine G.654 fiber with A_eff = 125 μm²: γ ≈ 0.92 W⁻¹km⁻¹ Terrestrial G.652 fiber with A_eff = 80 μm²: γ ≈ 1.44 W⁻¹km⁻¹ Impact: Submarine fiber allows ~56% higher launch power for the same nonlinear phase shift

Power Feeding Voltage Calculation

Submarine systems require precise power feeding voltage calculations to energize all repeaters while maintaining electrical safety margins. The calculation must account for every voltage drop in the electrical circuit.

V_total = V_cable + V_repeaters + V_ground + V_EPD + V_margin V_cable = I · R_cable_total where R_cable_total = L_total · R_per_km · (1 + α_temp·ΔT) V_repeaters = Σ(V_drop_i) for all N repeaters Typical: 150-350V per repeater depending on configuration V_ground = I · (R_ground_A + R_ground_B) Typical: 10-50 Ω per electrode V_EPD = Earth Potential Difference Nominal: 0.1 V/km, can reach hundreds of volts at high latitudes V_margin = Repair margin (typically 10-15% of total) Example: 6,000 km transoceanic system I = 1.2 A R_cable = 0.6 Ω/km → V_cable = 1.2 × 6000 × 0.6 = 4,320 V N = 60 repeaters @ 250V each → V_repeaters = 15,000 V V_ground = 1.2 × 60 = 72 V V_EPD = 0.1 × 6000 = 600 V V_margin = 0.15 × (4320 + 15000 + 72 + 600) = 2,999 V Total Required PFE Voltage = 22,991 V ≈ 23 kV This system requires voltage sharing between both terminals: Terminal A: +11.5 kV relative to earth Terminal B: -11.5 kV relative to earth

Key Technical Parameter Comparison Matrix

Detailed side-by-side comparison of critical system parameters

Types, Variations & Classifications

Both submarine and terrestrial optical systems encompass diverse implementations optimized for specific use cases, geographic constraints, and capacity requirements. Understanding these variations provides insight into how the fundamental design principles adapt to real-world deployment scenarios.

Submarine System Classifications

Submarine cable systems are classified primarily by reach, topology, and technical implementation. Unrepeatered systems span up to 400 kilometers without optical amplification, utilizing Remote Optically Pumped Amplifiers (ROPA) or high-launch-power terminal equipment. These systems connect islands to mainlands, link coastal cities, or provide redundant paths in metro areas.

Repeatered systems employ inline optical amplifiers and subdivide into regional (under 3,000 km), inter-regional (3,000-8,000 km), and transoceanic (over 8,000 km) categories. Shorter repeatered systems can utilize longer amplifier spacing (80-100 km) and higher gain amplifiers, while transoceanic cables optimize spacing at 60-70 km to maximize OSNR budget across hundreds of repeaters.

Applications: Island connections, coastal links, short crossings

Technology: ROPA, ultra-low loss fiber, high-power terminals

Advantages: No active wet plant, lower cost, simpler maintenance

Examples: Inter-island links in Southeast Asia, English Channel crossings

Applications: Regional connectivity, multi-country links

Technology: Long span (80-100 km), dual-stage amplifiers

Advantages: Cost-effective for moderate distances

Examples: Mediterranean systems, Southeast Asian networks

Applications: Intercontinental connectivity

Technology: Optimized spacing (60-70 km), single-stage amplifiers

Advantages: Maximum OSNR, proven reliability

Examples: Trans-Atlantic (TAT), Trans-Pacific (TPC), SEA-ME-WE

Applications: Multi-landing systems, resilient networks

Technology: Passive or ROADM branching units

Advantages: Connects multiple landing points, protection against failures

Examples: 2Africa (34 landings), Asia Pacific Gateway

Terrestrial Network Types

Terrestrial networks exhibit even greater diversity in topology and implementation. Metro networks typically deploy ring or mesh architectures with ROADM nodes, enabling wavelength-level protection and flexible bandwidth allocation within urban areas. Fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) access networks represent a distinct category focused on last-mile connectivity rather than long-haul transmission.

Long-haul terrestrial systems follow inter-city fiber routes, often paralleling highway or railway infrastructure. These systems may operate as point-to-point links between major metro areas, or as multi-hop networks with intermediate add-drop capability at regional hubs. The accessibility of terrestrial infrastructure enables hybrid architectures, such as data center interconnect (DCI) networks that combine dedicated dark fiber with carrier wavelength services.

Topology: Ring, mesh with ROADM

Amplifier Spacing: 80-120 km

Applications: City-to-city, regional connectivity

Key Features: High flexibility, frequent add-drop, protection switching

Topology: Point-to-point, hubbed

Amplifier Spacing: 80-100 km

Applications: Transcontinental backbone

Key Features: High capacity, optimized for reach, DCM common

Topology: Point-to-point, mesh

Technology: Dark fiber, coherent pluggables, 400G/800G

Applications: Cloud provider networks, hyperscale DC

Key Features: Ultra-low latency focus, high bandwidth per link

Applications: Mobile network (4G/5G)

Technology: CPRI/eCPRI over fiber, WDM-PON

Key Features: Strict latency requirements, TDD synchronization

Visual Demonstrations & Comparative Analysis

Physical Cable Construction: Cross-Sectional Comparison

Detailed view of submarine and terrestrial cable structures showing protection layers

Practical Applications & Case Studies

Real-world deployments of submarine and terrestrial systems demonstrate how theoretical design principles translate into operational networks. These case studies illustrate the distinct challenges, solutions, and trade-offs inherent to each domain.

Case Study 1: Trans-Atlantic Submarine System

A typical modern trans-Atlantic submarine cable system spans approximately 6,000 kilometers between the United States East Coast and the United Kingdom, with optional branching to France and other European landing points. The system design must balance competing requirements of maximum capacity, acceptable OSNR at the receiver, and compliance with the 25-year reliability target.

Design decisions for this class of system include: optimal repeater spacing of 60-70 km to maximize OSNR across 85-90 repeater spans; G.654.D fiber with 125 μm² effective area to minimize nonlinearity; Total Output Power control maintaining ±0.5 dB stability across all channels and the full 25-year lifetime; and power feeding at ±12 kV from each shore requiring sea ground electrodes rated for 1.2-1.5 A continuous current.

Case Study 2: Intercontinental Terrestrial Network

A transcontinental terrestrial backbone connecting data centers from New York to Los Angeles spans approximately 4,500 kilometers through 45-50 amplifier sites. Unlike submarine systems with fixed infrastructure, this terrestrial network evolved over 15 years through multiple technology generations.

The initial deployment in 2008 utilized 10 Gbps DWDM with 40 channels on standard G.652 fiber, achieving 400 Gbps total capacity. Amplifier sites deployed at existing telecommunications facilities with 80-100 km spacing, using AC-powered EDFA repeaters with automatic gain control and remote management via optical supervisory channels.

Capacity upgrades in 2015 introduced 100 Gbps coherent transmission across 80 channels, increasing total capacity to 8 Tbps without replacing the fiber plant. Additional ROADM nodes were installed at five major metro areas, enabling dynamic wavelength routing and restoration. In 2022, a further upgrade to 400 Gbps per wavelength using probabilistic constellation shaping achieved 32 Tbps capacity, with selected high-traffic routes upgraded to 800 Gbps using C+L band amplification.

Case Study 3: Hybrid Submarine-Terrestrial Integration

Modern network architectures increasingly blur the boundary between submarine and terrestrial domains through POP-to-POP connectivity. A representative implementation connects a hyperscale data center in Northern Virginia to a peer facility in Frankfurt, utilizing both submarine and terrestrial segments as a unified optical system.

The network path comprises 200 km of terrestrial fiber from the Virginia data center to a Cable Landing Station in Virginia Beach, a 6,200 km transatlantic submarine cable to a CLS in Cornwall, UK, and 800 km of terrestrial fiber through the UK and France to Frankfurt. Critical design considerations include end-to-end chromatic dispersion management spanning the complete 7,200 km path; optical power budget ensuring submarine repeaters receive appropriate input power despite terrestrial span loss variations; protection schemes isolating submarine cable faults from terrestrial segments; and unified network management correlating performance metrics across both domains.

Troubleshooting and Fault Management

Operational practices for fault detection and repair differ dramatically between submarine and terrestrial systems. Submarine systems rely on Coherent Optical Time Domain Reflectometry (C-OTDR) to locate cable breaks, with resolution of approximately 1-2 kilometers. Once a fault is localized, a specialized cable ship must be dispatched, often requiring 1-3 weeks depending on vessel availability, weather conditions, and distance to the fault location.

The cable ship uses a grapnel to snag and lift the cable from the seabed, cuts the cable at the fault location, repairs or replaces the damaged section, and splices the cable back together. The repair cable length affects system power budget, potentially requiring PFE voltage adjustment. Total repair time averages 3-6 weeks from fault detection to service restoration, with costs ranging from $1-5 million per repair operation.

Terrestrial systems benefit from road-accessible amplifier sites, enabling rapid fault response. Standard troubleshooting uses OTDR from terminal locations to identify failing spans or amplifier sites. Maintenance crews can reach most sites within hours, with equipment replacement or repair completed within a day. Protection schemes such as 1+1 or 1:N amplifier redundancy can restore service automatically within milliseconds, with field technicians dispatched for hardware replacement at the next maintenance window.

• Maximize repeater spacing to minimize component count

• Use ultra-low loss G.654 fiber with tight tolerance

• Implement comprehensive cable route surveys

• Design for worst-case environmental conditions

Installation:

• Avoid active seismic zones and fishing areas

• Bury cable in shallow water (depth < 1,000m)

• Verify sea ground electrode resistance pre-deployment

• Commission system with full OSNR characterization

Operations:

• Continuous C-OTDR monitoring for early fault detection

• Track repeater supervisory data for anomaly detection

• Maintain cable ship contracts for rapid response

• Implement diverse routing for critical links

• Leverage existing fiber when available

• Design amplifier sites for equipment evolution

• Implement 1+1 protection for high-availability links

• Plan for capacity growth (50% margin typical)

Installation:

• Verify fiber quality (OTDR trace) before acceptance

• Document fiber routes and splice points thoroughly

• Implement environmental alarms at all sites

• Commission with end-to-end path characterization

Operations:

• Regular site preventive maintenance (quarterly/annual)

• Remote monitoring with OSC and element management

• Maintain spare equipment inventory for rapid replacement

• Coordinate with fiber owners on right-of-way activities

Conclusion: Complementary Design Philosophies

Submarine and terrestrial optical fiber systems represent complementary approaches to long-distance data transmission, each optimized for its operational environment. Submarine systems embody a "deploy once, operate forever" philosophy, prioritizing extreme reliability, 25-year operational life, and maintenance-free operation in exchange for fixed capacity and limited flexibility. Terrestrial systems embrace evolutionary development, with accessible infrastructure enabling rapid technology upgrades, flexible network topologies, and adaptive capacity management.

The fundamental technical differences flow directly from environmental constraints. Submarine repeaters must operate in sealed pressure vessels at constant deep-ocean temperatures, powered remotely via high-voltage DC, with no possibility of repair or replacement for 25 years. This drives design choices favoring redundancy, conservative power margins, and precision manufacturing with tight component tolerance. Terrestrial amplifiers benefit from AC power, climate-controlled shelters, and accessibility for maintenance, enabling higher performance through active thermal management, variable gain control, and incremental technology refresh.

Modern network architectures increasingly integrate both domains into unified optical systems. The trend toward POP-to-POP connectivity extends submarine terminals beyond Cable Landing Stations directly into urban data centers, creating hybrid systems that must reconcile submarine reliability requirements with terrestrial flexibility benefits. ROADM-based terminal equipment provides the interface technology enabling seamless optical bypass, dynamic capacity allocation, and protection switching across domain boundaries.

As international data traffic continues exponential growth, both submarine and terrestrial infrastructure must evolve to meet capacity demands. Submarine systems are exploring space-division multiplexing with multi-core and multi-mode fibers, C+L band amplification, and advanced coherent modulation. Terrestrial networks are deploying 800G per wavelength transponders, artificial intelligence for network optimization, and dense wavelength grid ROADMs. Despite different pathways, both domains converge toward the same goal of petabit-scale capacity supporting global digital connectivity.

For optical networking professionals, understanding the distinct design philosophies and technical approaches of submarine versus terrestrial systems is essential for effective system planning, equipment selection, and network operations. While the fundamental physics of optical propagation remains constant, successful implementation requires recognizing how environmental conditions, reliability requirements, and operational constraints shape every aspect of system architecture from fiber selection to power feeding to fault management.

10 Key Takeaways

References

- ITU-T Recommendation G.971, "General features of optical fibre submarine cable systems," International Telecommunication Union, 2024.

- ITU-T Recommendation G.972, "Definition of terms relevant to optical fibre submarine cable systems," International Telecommunication Union, 2024.

- Antona, J.C., "Submarine Optical Fiber Communication Systems - OFC 2020 Short Course," Alcatel Submarine Networks, 2020.

- Chesnoy, J. (Editor), "Undersea Fiber Communication Systems," Academic Press, 2016. Chapters: Submarine Fibers (Ch11), Submerged Plant Equipment (Ch12), Cable Technology (Ch13), Marine and Maintenance (Ch17).

- Sanjay Yadav, "Optical Network Communications: An Engineer's Perspective." Bridge the Gap Between Theory and Practice in Optical Networking.

For educational purposes in optical networking and DWDM systems

Note: This guide is based on industry standards, best practices, and real-world implementation experiences. Specific implementations may vary based on equipment vendors, network topology, and regulatory requirements. Always consult with qualified network engineers and follow vendor documentation for actual deployments.

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here