Optical networks are the backbone of the internet, carrying vast amounts of data over great distances at the speed of light. However, maintaining signal quality over long fiber runs is a challenge due to a phenomenon known as noise concatenation. Let’s delve into how amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) noise affects Optical Signal-to-Noise Ratio (OSNR) and the performance of optical amplifier chains.

The Challenge of ASE Noise

ASE noise is an inherent byproduct of optical amplification, generated by the spontaneous emission of photons within an optical amplifier. As an optical signal traverses through a chain of amplifiers, ASE noise accumulates, degrading the OSNR with each subsequent amplifier in the chain. This degradation is a crucial consideration in designing long-haul optical transmission systems.

Understanding OSNR

OSNR measures the ratio of signal power to ASE noise power and is a critical parameter for assessing the performance of optical amplifiers. A high OSNR indicates a clean signal with low noise levels, which is vital for ensuring data integrity.

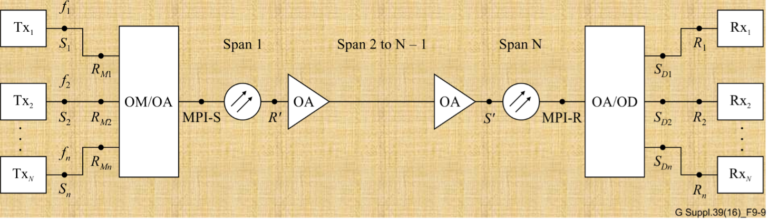

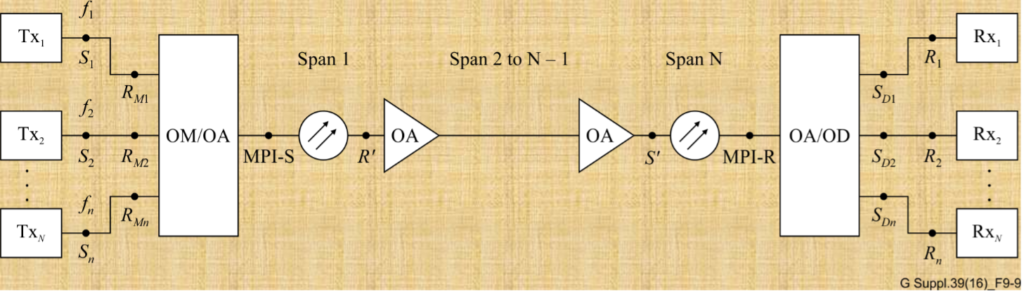

Reference System for OSNR Estimation

As depicted in Figure below), a typical multichannel N span system includes a booster amplifier, N−1 line amplifiers, and a preamplifier. To simplify the estimation of OSNR at the receiver’s input, we make a few assumptions:

- All optical amplifiers, including the booster and preamplifier, have the same noise figure.

- The losses of all spans are equal, and thus, the gain of the line amplifiers compensates exactly for the loss.

- The output powers of the booster and line amplifiers are identical.

Estimating OSNR in a Cascaded System

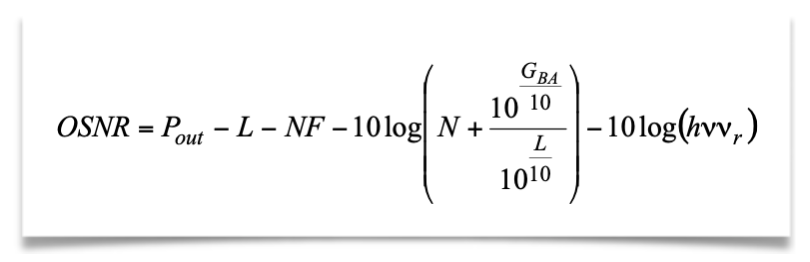

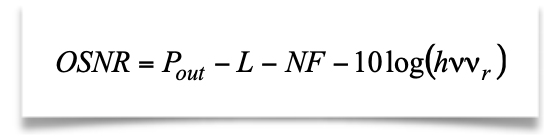

E1: Master Equation For OSNR

Pout is the output power (per channel) of the booster and line amplifiers in dBm, L is the span loss in dB (which is assumed to be equal to the gain of the line amplifiers), GBA is the gain of the optical booster amplifier in dB, NFis the signal-spontaneous noise figure of the optical amplifier in dB, h is Planck’s constant (in mJ·s to be consistent with Pout in dBm), ν is the optical frequency in Hz, νr is the reference bandwidth in Hz (corresponding to c/Br ), N–1 is the total number of line amplifiers.

The OSNR at the receivers can be approximated by considering the output power of the amplifiers, the span loss, the gain of the optical booster amplifier, and the noise figure of the amplifiers. Using constants such as Planck’s constant and the optical frequency, we can derive an equation that sums the ASE noise contributions from all N+1 amplifiers in the chain.

Simplifying the Equation

Under certain conditions, the OSNR equation can be simplified. If the booster amplifier’s gain is similar to that of the line amplifiers, or if the span loss greatly exceeds the booster gain, the equation can be modified to reflect these scenarios. These simplifications help network designers estimate OSNR without complex calculations.

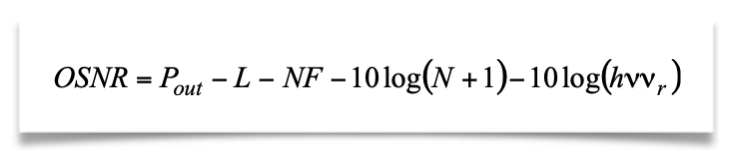

1) If the gain of the booster amplifier is approximately the same as that of the line amplifiers, i.e., GBA » L, above Equation E1 can be simplified to:

E1-1

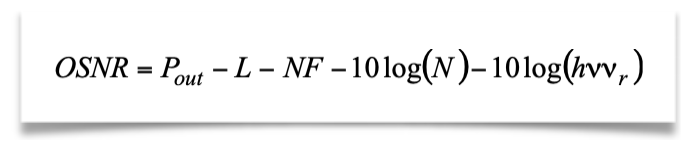

2) The ASE noise from the booster amplifier can be ignored only if the span loss L (resp. the gain of the line amplifier) is much greater than the booster gain GBA. In this case Equation E1-1 can be simplified to:

E1-2

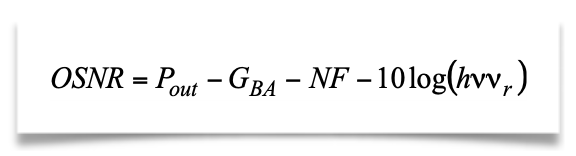

3) Equation E1-1 is also valid in the case of a single span with only a booster amplifier, e.g., short‑haul multichannel IrDI in Figure 5-5 of [ITU-T G.959.1], in which case it can be modified to:

E1-3

4) In case of a single span with only a preamplifier, Equation E1 can be modified to:

Practical Implications for Network Design

Understanding the accumulation of ASE noise and its impact on OSNR is crucial for designing reliable optical networks. It informs decisions on amplifier placement, the necessity of signal regeneration, and the overall system architecture. For instance, in a system where the span loss is significantly high, the impact of the booster amplifier on ASE noise may be negligible, allowing for a different design approach.

Conclusion

Noise concatenation is a critical factor in the design and operation of optical networks. By accurately estimating and managing OSNR, network operators can ensure signal quality, minimize error rates, and extend the reach of their optical networks.

In a landscape where data demands are ever-increasing, mastering the intricacies of noise concatenation and OSNR is essential for anyone involved in the design and deployment of optical communication systems.