31 min read

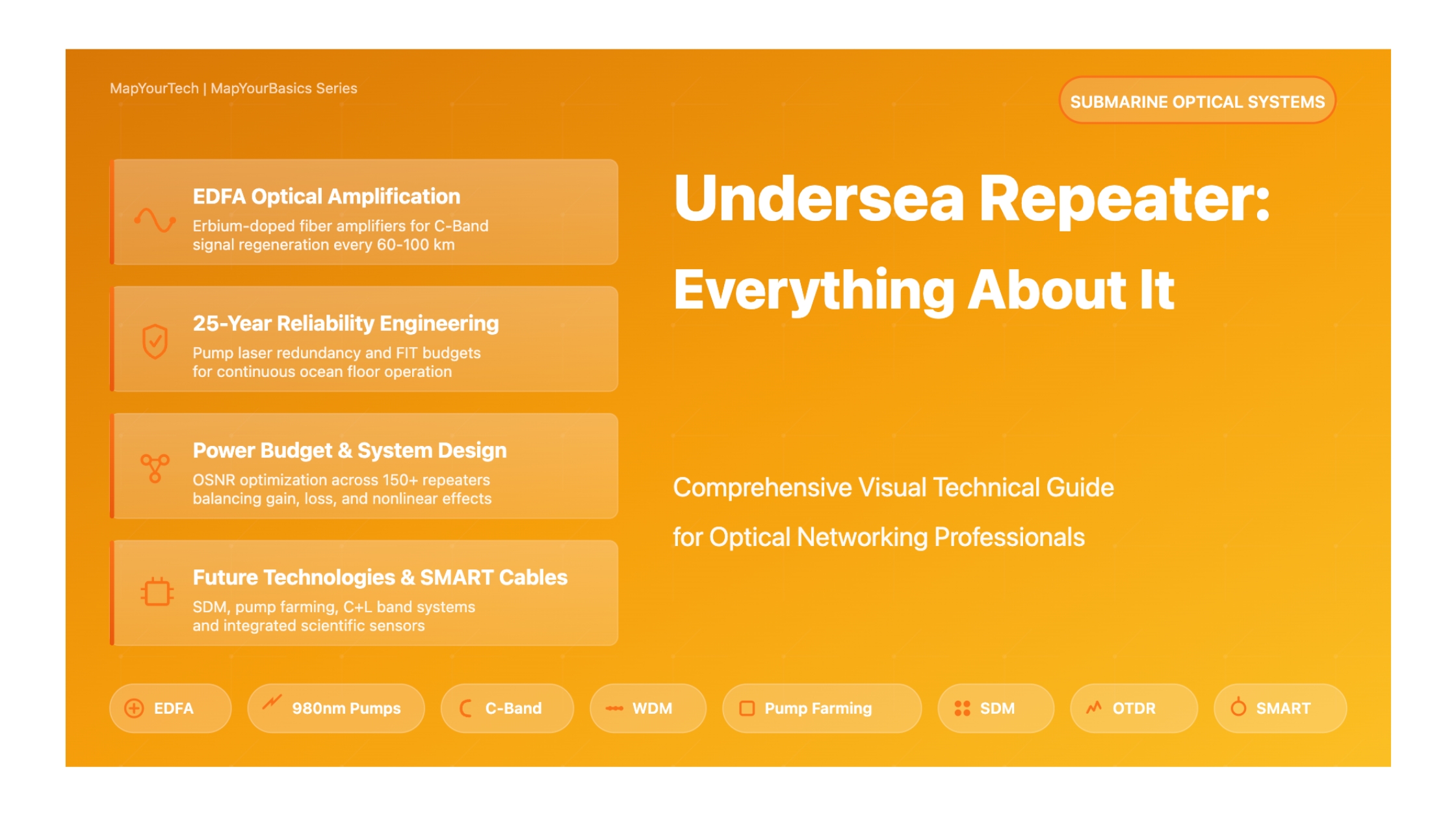

Undersea Repeater: Everything About It

Comprehensive Visual Technical Guide for Optical Networking Professionals

Practical Information Based on Experience and Industry RequirementsIntroduction

Undersea repeaters represent one of the most critical yet least visible components of global telecommunications infrastructure. These sophisticated devices enable the transmission of data across vast ocean distances, connecting continents and making modern internet communication possible. More than 99% of intercontinental internet traffic travels through undersea fiber optic cables, and repeaters are the vital amplification stations that keep signals strong across thousands of kilometers of ocean floor.

An undersea repeater is essentially a pressure-sealed housing containing optical amplifiers that regenerate weakened optical signals as they traverse the ocean floor. Unlike terrestrial optical amplifiers that can be easily accessed for maintenance or replacement, undersea repeaters must operate continuously for 25 years at depths reaching 8,000 meters or more, under pressures exceeding 800 atmospheres, in complete darkness, and without any possibility of repair without a costly cable ship intervention.

The fundamental purpose of an undersea repeater is to compensate for signal attenuation that occurs as light travels through optical fiber. Even with the highest quality fiber, optical signals degrade over distance due to various loss mechanisms. In a typical transoceanic cable system spanning 10,000 kilometers, signals might pass through 100 to 150 repeaters, each precisely amplifying the weakened optical carriers back to usable power levels.

Why Undersea Repeaters Are Critical

Without repeaters, undersea fiber optic communication would be limited to a few hundred kilometers at most. The combination of fiber attenuation, chromatic dispersion, and other transmission impairments would render long-distance communication impossible. Modern repeaters using erbium-doped fiber amplifiers have enabled the explosion of global internet connectivity by:

- Amplifying optical signals transparently without electrical conversion

- Supporting wavelength-division multiplexing with 80+ simultaneous channels

- Operating continuously for 25 years without maintenance

- Withstanding extreme pressures up to 1000 atmospheres

- Functioning in near-freezing water temperatures around 1-5°C

- Enabling multi-terabit capacity on single cable systems

Key Fact: Global Dependence on Undersea Cables

Over 99% of intercontinental internet traffic travels through undersea fiber optic cables. As of 2025, there are more than 500 active undersea cable systems spanning over 1.3 million kilometers globally, with combined capacity exceeding 1000 terabits per second. The value of new cable installations between 2022-2025 exceeded $10 billion, driven primarily by tech giants like Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta.

Historical Context and Evolution

The history of undersea repeaters mirrors the evolution of telecommunications technology itself, progressing from basic signal regeneration to sophisticated optical amplification systems.

The Coaxial Cable Era (1950s-1980s)

Before optical fiber, undersea telecommunications relied on coaxial copper cables with electronic repeaters. The first transatlantic telephone cable, TAT-1, was laid in 1956 and could carry just 36 simultaneous telephone conversations. These early repeaters were essentially analog amplifiers that boosted electrical signals. They were large, power-hungry, and required sophisticated vacuum tube technology that had to survive decades on the ocean floor.

Electronic repeaters faced significant limitations including limited bandwidth, high power consumption, and the need for frequent spacing every 10-20 kilometers. The maximum achievable data rate was constrained by the bandwidth limitations of coaxial cable and the complexity of high-frequency electronics.

Optical Era Begins: TAT-8 (1988)

The first transatlantic optical fiber cable, TAT-8, represented a revolutionary leap in technology. Commissioned in 1988, it used optical fibers and optical-electrical-optical repeaters that converted optical signals to electrical signals for amplification, then back to optical for transmission. TAT-8 operated at 280 Mbps and could carry 40,000 simultaneous telephone calls, a dramatic improvement over previous systems.

However, these early optical repeaters still relied on complex electronics. Each repeater contained photodiodes to detect incoming optical signals, electronic amplifiers to boost the electrical signals, and laser diodes to convert the signal back to light. This OEO conversion limited data rates and increased complexity.

The EDFA Revolution (1995)

The introduction of erbium-doped fiber amplifiers in the mid-1990s transformed undersea telecommunications. EDFAs amplify light directly in the optical domain without any electrical conversion. This breakthrough enabled several critical advantages including transparency to data rate and modulation format, support for wavelength-division multiplexing, lower power consumption, and simplified repeater design with improved reliability.

The first EDFA-based transatlantic cables were deployed in 1995, including TAC, built jointly by leading vendors. These systems demonstrated multi-gigabit capacity and paved the way for the modern internet era.

Modern Era: WDM and Beyond (2000-Present)

From 2000 onward, wavelength-division multiplexing transformed undersea capacity. Modern repeaters amplify 80 or more wavelength channels simultaneously across the C-band spectrum. Each channel can carry 100 Gbps or more using coherent modulation formats. System capacity has grown exponentially, with modern cables supporting 10-50 terabits per second, and next-generation systems targeting 500+ terabits per second using space-division multiplexing with 16-24 fiber pairs per cable.

Recent innovations include pump farming architectures where pump lasers are shared among multiple fiber pairs for improved redundancy, integration of scientific monitoring sensors for tsunami detection and seismology, remote optically pumped amplifiers for unrepeated systems, and C+L band systems expanding the usable spectrum beyond 80 nm.

Core Concepts and Fundamentals

Understanding undersea repeaters requires knowledge of several fundamental optical and physical principles that govern their operation.

Signal Attenuation and the Need for Amplification

Optical signals traveling through fiber experience loss due to several mechanisms. Modern single-mode fiber optimized for 1550 nm wavelengths exhibits attenuation around 0.2 dB/km. While this seems small, over long distances the cumulative loss becomes severe. For a 10,000 km transoceanic cable, the total fiber loss would be approximately 2000 dB without amplification.

To put this in perspective, 2000 dB of loss means the signal would be attenuated by a factor of 10^200, which is an incomprehensibly small fraction. The signal would be completely lost in noise within just a few hundred kilometers. This is why repeaters are essential, typically spaced every 60-100 km to maintain adequate optical signal-to-noise ratio.

Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers: The Heart of Modern Repeaters

Modern undersea repeaters use erbium-doped fiber amplifiers as their core amplification technology. An EDFA consists of a length of optical fiber whose core has been doped with erbium ions. When these ions are excited by pump light at 980 nm or 1480 nm wavelengths, they can amplify signals in the 1525-1568 nm C-band range through stimulated emission.

The amplification process works through these key steps. First, pump light from laser diodes excites erbium ions from their ground state to higher energy levels. Signal photons at 1550 nm interact with excited erbium ions, causing stimulated emission of additional photons at the same wavelength and phase. This results in optical gain, typically 10-15 dB per repeater, achieved with low noise figure around 4.5-5.0 dB. The process is transparent to data rate and modulation format, and supports simultaneous amplification of multiple wavelength channels.

The quantum mechanical process underlying EDFAs relies on the electronic energy level structure of erbium ions in silica glass. The metastable excited state has a relatively long lifetime of approximately 10 milliseconds, which allows for population inversion and efficient amplification.

Technical Specification: Typical EDFA Parameters

- Gain: 10-15 dB per stage

- Output Power: +12 to +17 dBm

- Noise Figure: 4.5-5.0 dB

- Gain Bandwidth: 30-40 nm (C-band: 1525-1568 nm)

- Pump Wavelength: 980 nm (most common for low noise)

- Pump Power: 100-500 mW per amplifier

- EDF Length: 10-30 meters

Optical Signal-to-Noise Ratio: The Critical Performance Metric

The optical signal-to-noise ratio is the most important performance parameter for undersea optical transmission systems. OSNR quantifies the ratio between signal power and optical noise power within a reference bandwidth, typically measured in a 0.1 nm (12.5 GHz) bandwidth at 1550 nm.

EDFAs introduce noise through amplified spontaneous emission. Even in an ideal amplifier, quantum mechanics dictates a minimum noise figure of 3 dB, corresponding to the addition of one photon of noise per photon of signal gain. Practical amplifiers have noise figures of 4.5-5 dB due to component losses and imperfect population inversion.

For a chain of N identical amplifiers, each with gain G and noise figure NF, the cumulative OSNR at the output can be approximated by the formula: OSNR = (Pout / N·NF·hν·B0), where Pout is the amplifier output power, h is Planck's constant, ν is the optical frequency, and B0 is the reference bandwidth. This shows that OSNR degrades linearly with the number of amplifiers, making noise accumulation a fundamental limit for long-haul systems.

Modern coherent detection systems using advanced modulation formats like 16-QAM or 64-QAM require OSNR values of 15-25 dB or higher for error-free operation. This requirement drives the entire system design, from repeater spacing to amplifier output power to fiber type selection.

Technical Architecture and Components

A modern undersea repeater is a marvel of engineering, integrating optical, electrical, and mechanical systems into a hermetically sealed package designed to survive 25 years on the ocean floor. Understanding the architecture requires examining both the optical amplification chain and the supporting infrastructure.

Amplifier Pair Architecture

The fundamental building block of an undersea repeater is the amplifier pair. Each fiber pair in the cable requires one amplifier pair for bidirectional communication. The two amplifiers are optically independent, providing signal amplification in opposite propagation directions, but they typically share a redundant set of pump lasers for improved reliability.

A typical repeater contains 4 to 8 amplifier pairs, corresponding to 4 to 8 fiber pairs in the cable. Advanced systems now support up to 16 fiber pairs per repeater using space-division multiplexing architectures. Each amplifier in the pair contains a precisely designed optical chain including input isolator, pump wavelength combiner, erbium-doped fiber gain section, output isolator, gain flattening filter, and high-loss loopback path for monitoring.

Critical Optical Components

Optical Isolators

Optical isolators are unidirectional devices that allow light to pass in one direction while blocking reflections in the reverse direction. Modern undersea amplifiers use three isolators per amplifier. The input isolator prevents backward propagating amplified spontaneous emission from entering the input fiber, which would degrade noise figure through Rayleigh backscattering. The first output isolator prevents signal reflections from consuming pump power. The second output isolator, placed after the gain flattening filter, blocks external reflections from reaching the GFF, which can be a significant source of back-reflection.

Pump Laser Units

Pump lasers provide the optical power necessary to excite erbium ions. Modern systems use 980-nm pump lasers due to their higher power efficiency and lower amplifier noise figure compared to 1480-nm pumps. These lasers are wavelength-stabilized using fiber Bragg gratings to ensure operation in the coherent collapse regime, reducing output power fluctuations and stabilizing the lasing wavelength.

Critically, pump lasers in undersea applications are always passively cooled rather than using active Peltier coolers. This design choice reduces electrical power consumption and significantly increases laser reliability. The deep ocean provides a stable thermal environment at approximately 1-5°C, eliminating the need for active thermal management.

Pump redundancy is essential for system reliability. Modern designs use shared pumping configurations where multiple pump lasers feed both amplifiers in a pair through optical combiners and splitters. When a single pump laser fails, the remaining lasers maintain amplification with reduced output power. Since undersea amplifiers operate in deep gain saturation, subsequent repeaters can compensate for most of the power loss with negligible system performance degradation.

Erbium-Doped Fiber

The EDF itself is typically 10-30 meters long and contains erbium ions at concentrations of 100-1000 parts per million. The fiber is co-doped with aluminum to increase solubility of erbium and reduce clustering. Specific care is taken to ensure uniform erbium concentration along the fiber length and consistent aluminum concentration to maintain stable gain spectrum characteristics over the 25-year lifetime.

Gain Flattening Filters

Gain equalization is far more critical for undersea systems than terrestrial systems because transoceanic routes may include 150 or more amplified spans. Any residual gain shape error accumulates catastrophically. Modern systems support more than 30 nm of gain bandwidth in the C-band, and the natural erbium gain shape exhibits more than 2 dB of wavelength dependence that must be compensated.

GFFs are implemented using various technologies including short-period fiber Bragg gratings, long-period gratings, slanted gratings, thin-film filters, and tapered fiber filters. Each technology has tradeoffs between matching capability, spectral smoothness, and insertion loss. The filter must meet stringent requirements for temperature stability, low polarization dependent loss, low polarization mode dispersion, and minimal variation between manufactured units.

Beyond the per-repeater GFFs, systems also deploy gain tilt equalizers every 20 repeaters to compensate for accumulated tilt errors, and shape control filters to address systematic gain shape deviations measured during manufacturing.

High-Loss Loopback Path

The HLLB path enables optical time-domain reflectometry for cable fault localization and system monitoring. It consists of passive optical couplers that tap a small portion of the amplifier output signal and couple it back into the counter-propagating amplifier. During OTDR measurements, the HLLB couples the backscattered signal from the fiber span back into the opposite amplifier. Some systems include wavelength-selective gratings in the HLLB to reflect only specific monitoring wavelengths while allowing data traffic to pass unimpeded.

Power Feed Architecture

Undersea repeaters receive electrical power through the cable itself. A copper conductor within the cable structure carries DC current from shore-based power feed equipment. Systems typically operate at line currents up to 1.5 amperes and voltages reaching 15,000 volts for long transoceanic cables. The repeater electronics convert this high-voltage DC to the various voltages needed for pump laser operation and control circuits.

The total power budget is a critical system constraint. Each repeater consumes 20-40 watts depending on the number of amplifier pairs and pump configuration. For a 10,000 km cable with 150 repeaters, total power consumption might reach 4-6 kilowatts. This power must be delivered efficiently while maintaining electrical isolation between the cable conductor and seawater ground potential.

Mechanical and Pressure Housing Design

The repeater housing must create a stable environment for precision optical components while withstanding extreme external pressures. At 8,000 meters depth, the hydrostatic pressure reaches approximately 800 atmospheres or 80 megapascals. The housing must maintain structural integrity over 25 years while experiencing negligible physical deformation that could misalign optical connections.

Modern repeater housings are fabricated from beryllium-copper alloys due to their exceptional combination of strength, thermal conductivity, and corrosion resistance. The ultimate tensile strength rivals steel while corrosion resistance is superior, ensuring consistent performance over the system lifetime. Alternative materials include titanium, various stainless steel alloys, and composite structures, each with specific tradeoffs in thermal management, weight, and cost.

Thermal management is critical yet simpler than terrestrial systems. The deep ocean maintains a stable temperature around 1-5°C. Heat dissipation occurs passively through the housing wall to surrounding seawater. The housing is designed to efficiently conduct heat from pump lasers to the outer surface. No active cooling is required, eliminating a major reliability concern. Shallow water repeaters require special consideration to handle higher ambient temperatures without Peltier cooling, maintaining passive thermal management throughout.

During deployment, repeaters experience significant mechanical shocks as they pass over ship machinery, potentially reaching 20g accelerations. The internal optical network must be rigidly mounted to prevent fiber movement or connection degradation. Qualification testing includes extensive vibration and shock testing to verify mechanical robustness.

Reliability Engineering and 25-Year Lifetime

The defining characteristic of undersea repeaters is their requirement for uninterrupted 25-year operation without maintenance or replacement. This drives every aspect of design, component selection, and manufacturing. Repair of a failed repeater requires a cable ship intervention costing millions of dollars and potentially weeks of service disruption.

Reliability Fundamentals and FIT Budgets

Reliability engineering uses the FIT as the standard metric, where one FIT equals one failure in 10^9 device-hours. System-level reliability is calculated from component-level FIT rates, with most components configured in series such that any single failure causes system failure. The exception is redundant components like pump lasers, where multiple failures must occur before system failure.

For a 25-year lifetime, the probability of failure must be kept below acceptable thresholds, typically requiring that cable ship repairs due to equipment failure occur less than once per system lifetime. A representative FIT budget for a modern repeater might allocate pump lasers at 1-10 FIT per laser, discrete optical components at 0.1-0.2 FIT each, optical fiber splices at 0.01 FIT, integrated circuits at 0.2 FIT, and passive electronics at 0.01-0.2 FIT. The total per amplifier pair, accounting for laser redundancy, might be 4-6 FIT, with a complete 4-pair repeater totaling approximately 21 FIT.

Pump Laser Reliability and Redundancy

Pump lasers are the most critical reliability concern. These semiconductor devices operate continuously at elevated current densities, slowly degrading over time. To ensure 25-year operation, extensive accelerated life testing is performed at elevated temperatures using Arrhenius extrapolation. Testing at 70-85°C for 6 months can predict behavior over 25 years at actual operating temperatures near 20°C.

Multiple levels of redundancy protect against pump failure. The most common architecture uses 2+2 redundancy where two pump lasers serve each amplifier, but systems increasingly employ 4+4 or higher redundancy with pump farming. Modern pump farming architectures pool 6 or more pump lasers serving multiple fiber pairs, providing tolerance for 3 or more pump failures without service impact.

When a pump fails, the system operates in a degraded but functional state. The reduced pump power lowers amplifier output power by 1-2 dB, but because amplifiers operate in gain saturation, subsequent repeaters can compensate for most of this power loss. System OSNR degrades slightly but remains within acceptable margins.

Manufacturing Quality Control

Every component must meet stringent quality standards. Optical components undergo extensive screening for insertion loss, back-reflection, polarization effects, and environmental stability. Erbium-doped fiber is characterized for erbium concentration uniformity, aluminum co-dopant consistency, and splice loss. Pump lasers are subjected to burn-in testing and wavelength verification.

After assembly, complete amplifier chains are tested as integrated units. Measurements include gain spectrum across all channels, noise figure, output power capabilities, and response to pump failures. Temperature cycling verifies performance stability. Any out-of-specification unit is rejected or reworked.

Factory acceptance testing of complete repeaters includes pressure testing to full depth rating, high-voltage insulation testing, and environmental stress screening using random vibration to detect subtle fiber movements or connection issues that could develop into failures at sea.

Field Performance Data

Actual field data from deployed systems validates the reliability engineering approach. Systems installed in the 1990s and 2000s have now accumulated 15-25 years of operational data. Pump laser failure rates measured in the field closely match predictions from accelerated testing. Modern systems show even better reliability as manufacturing processes mature and pump laser designs improve.

Operators monitor repeater performance continuously through supervisory telemetry. Pump currents are tracked to detect degradation trends. Optical power levels at amplifier inputs and outputs are measured. Temperature sensors within repeaters provide environmental monitoring. This data enables predictive maintenance strategies and informs future system designs.

System Design, Repeater Spacing, and Power Budget

The design of an undersea optical system involves complex tradeoffs between repeater spacing, amplifier output power, OSNR requirements, fiber characteristics, and total system capacity. These parameters are not independent but form an interconnected design space that must be optimized for each specific route.

Repeater Spacing Determination

Repeater spacing typically ranges from 50 to 100 kilometers, determined by the balance between fiber attenuation and required OSNR. Closer spacing means more repeaters, higher cost, more potential failure points, and greater complexity, but provides better OSNR and enables higher capacity. Wider spacing reduces repeater count and cost but degrades OSNR and may limit capacity.

The optimal spacing depends on several factors including fiber loss coefficient, amplifier output power capabilities, noise figure specifications, required end-of-life OSNR for the chosen modulation format, and nonlinear effects that limit maximum signal power. For a modern C-band system with 80 channels, typical spacing might be 70-80 km, while future systems with higher channel counts or more complex modulation formats might require 60-70 km spacing to maintain OSNR.

The total number of repeaters in a transoceanic cable can be substantial. A 10,000 km transpacific system with 70 km spacing requires approximately 140 repeaters. Each repeater represents a significant capital investment, typically $500,000 to over $1 million depending on fiber pair count and technology features.

Nonlinear Effects and Power Limitations

While one might think simply increasing amplifier output power would solve all problems, fiber nonlinearities impose strict limits on signal power. At high optical powers, several nonlinear effects degrade transmission including self-phase modulation, cross-phase modulation, four-wave mixing, and stimulated Raman scattering.

These effects scale with optical intensity and fiber length, making them particularly problematic for undersea systems with their long spans. The result is that per-channel powers must be limited to around -1 to +2 dBm, depending on fiber effective area, channel spacing, modulation format, and total system length. This constraint drives the entire power budget optimization.

Modern systems use large effective area fibers to mitigate nonlinearities. LEAF, TeraWave, and similar fibers provide effective areas of 70-110 μm² compared to 50-60 μm² for standard single-mode fiber. This allows slightly higher per-channel powers while maintaining acceptable nonlinear penalties.

Capacity Scaling and Modulation Formats

Modern undersea systems achieve multi-terabit capacities through dense wavelength-division multiplexing combined with advanced modulation formats. Typical configurations deploy 80-100 wavelength channels spaced at 50 GHz in the C-band. Each channel uses coherent modulation formats such as DP-QPSK, DP-16QAM, or even DP-64QAM, carrying 100-400 Gbps per wavelength.

The choice of modulation format involves a fundamental tradeoff. Higher-order modulation formats like 64-QAM pack more bits per symbol, increasing capacity, but require higher OSNR to achieve acceptable bit error rates. Lower-order formats like QPSK are more robust to noise but carry fewer bits per symbol. System designers must match the modulation format to the available OSNR determined by repeater spacing and count.

Recent systems explore spectral superchannels where multiple carriers are grouped and jointly processed. This approach improves spectral efficiency and enables flexible rate adaptation. Future systems may employ probabilistic constellation shaping and nonlinear compensation in digital signal processors to further push capacity limits.

Monitoring, Supervisory Systems, and Future Technologies

Supervisory Telemetry and System Monitoring

Modern undersea repeaters include sophisticated supervisory capabilities that enable remote monitoring and control. The supervisory system communicates with repeaters using low-frequency amplitude modulation superimposed on the optical signal. A typical implementation uses pulse-width modulation with a carrier frequency around 10-50 kHz, carefully chosen to avoid interaction with the EDFA's frequency response while remaining detectable after passing through the amplifier chain.

Shore equipment sends supervisory commands by modulating the aggregate optical signal with a low modulation index, typically around 4%. Each repeater includes an envelope detector to recover these commands. The repeater responds by modulating its pump current, which in turn modulates the amplifier gain at a different frequency, typically 1-5 kHz. This modulation propagates back to the shore terminal where it's demodulated to recover status information.

The supervisory system enables measurement of amplifier input and output powers, pump laser currents, internal temperatures, and detection of intermittent faults. Commands can set pump power levels, switch between redundant components, and configure active gain control devices if present. This telemetry is essential for system commissioning, performance monitoring during operation, and troubleshooting when problems occur.

OTDR and Fault Localization

Optical time-domain reflectometry enables precise localization of fiber faults. An OTDR system launches optical pulses into the fiber and measures backscattered light versus time. Rayleigh scattering in the fiber creates a continuous backscattered signal proportional to the fiber attenuation profile. Discrete reflections from fiber breaks, connector interfaces, or other discontinuities appear as spikes in the OTDR trace.

In undersea systems, the OTDR operates through the high-loss loopback paths in repeaters. A pulse launched from shore travels through multiple repeater spans. At each repeater, the HLLB path reflects a portion of the backscattered light from the following span into the counter-propagating amplifier, where it's amplified and travels back to shore. This allows measurement of the attenuation profile of every span individually, enabling fault location to within 1-2 km.

When a cable fault occurs, OTDR measurements from both cable ends quickly identify the fault location. This information is critical for dispatching a cable ship with the correct repair equipment and planning the repair operation. Modern systems achieve OTDR measurement precision better than 1 km over transoceanic distances.

SMART Cables: Integrating Scientific Sensors

An exciting development is the integration of scientific monitoring sensors into submarine cables, creating Science Monitoring And Reliable Telecommunications cables. SMART cables add temperature sensors, pressure sensors, and seismometers to repeater housings, enabling continuous monitoring of ocean conditions and seismic activity.

The scientific value is substantial. Temperature and pressure data help monitor ocean circulation, heat content, and climate change impacts. Seismometers enable earthquake detection and tsunami warning, particularly valuable in seismically active regions like the Pacific Ring of Fire. The UN's joint task force is actively promoting SMART technology through pilot projects in high-risk areas.

From a telecommunications perspective, adding sensors increases repeater complexity and power consumption, but the additional requirements are modest. Modern repeater designs can accommodate sensor packages with minimal impact on telecommunications performance. Several systems incorporating SMART functionality are already deployed or in planning stages.

C+L Band Systems

Extending amplification beyond the C-band into the L-band offers a pathway to doubling spectral capacity. L-band EDFAs operate from approximately 1565 to 1610 nm, adding 40+ nm to the usable spectrum. However, L-band amplification presents technical challenges.

L-band EDFAs require different operating conditions than C-band amplifiers. The erbium ion population inversion must be reduced to around 40%, compared to 60-70% for C-band operation. This results in lower gain efficiency and slightly higher noise figures, typically 0.5 dB worse than C-band. Gain equalization is somewhat simpler due to the smoother gain spectrum, but overall system OSNR is reduced.

Despite these challenges, C+L systems are increasingly deployed, particularly for high-capacity regional routes where the OSNR penalty is acceptable. Future improvements in L-band EDFA technology may enable wider adoption for transoceanic systems.

Space-Division Multiplexing

The most dramatic capacity increases come from space-division multiplexing, where multiple fiber pairs share a single cable. Early systems used 2-4 fiber pairs, modern systems support 8-16 pairs, and next-generation designs target 24 or more pairs.

Pump farming enables efficient SDM implementation. Rather than dedicating separate pump lasers to each fiber pair, a pool of pump lasers serves all amplifiers through an optical coupler network. This provides maximum flexibility and redundancy while optimizing power consumption. When properly designed, pump farming allows systems to tolerate multiple pump failures without service degradation.

The challenging aspects of SDM include increased repeater size to accommodate more amplifiers, higher total power consumption requiring larger power feed equipment, more complex optical coupling networks, and heat dissipation from higher pump densities. Despite these challenges, SDM is the primary pathway to achieving 500+ terabit per second system capacities demanded by future traffic growth.

Real-World Implementation and Case Studies

Cable Installation Process

Installing an undersea cable system is a complex operation requiring specialized vessels and precise navigation. Cable ships carry thousands of kilometers of cable and repeaters, deploying them at controlled speeds typically 5-8 knots. Modern installation uses dynamic positioning and real-time depth profiling to lay cable following optimal routes.

Repeaters present special handling requirements. During deployment, they pass through cable machinery on the ship's stern, experiencing significant mechanical stress and shock loads up to 20g. The cable-to-repeater transitions use tapered sections and bend limiters to enable smooth passage through ship equipment while protecting the fiber connections inside.

Route surveys precede installation, using multibeam sonar and remotely operated vehicles to map the seabed, identify obstacles, and locate optimal landing points. The goal is to avoid areas with steep slopes, active fishing grounds, seismic zones, and regions with rocky outcrops or coral reefs that could damage cable.

Case Study: Transatlantic System Design

Consider a modern transatlantic cable system connecting New York to London, approximately 5,500 kilometers. System designers must balance numerous requirements to optimize performance and cost.

Route selection avoids fishing grounds, shipping lanes, and seismically active areas while minimizing total distance. Water depths range from a few hundred meters near shore to 3,000-5,000 meters in the deep Atlantic. The route crosses the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, requiring careful path selection through underwater canyons.

With 75 km repeater spacing, the system requires approximately 73 repeaters. Each repeater might contain 8 fiber pairs using pump farming with 6-8 redundant pump lasers. C-band operation with 96 channels at 50 GHz spacing, each carrying 200 Gbps using DP-16QAM, yields 19.2 terabits per fiber pair or 154 terabits total system capacity.

Power feed equipment at each cable station provides 1.2 amperes at approximately 9,000 volts. Total cable power consumption might be 2,400 watts, split between the two cable ends. The system design life is 25 years with expected repair frequency less than one ship repair per system lifetime due to equipment failure.

Case Study: Transpacific Ultra-Long-Haul

Transpacific routes present even greater challenges. A system connecting Los Angeles to Tokyo spans approximately 9,000 kilometers across the Pacific Ocean. Water depths exceed 6,000 meters in many areas, with some routes crossing regions deeper than 8,000 meters.

Repeater spacing must be carefully chosen to balance OSNR requirements against the large number of amplifiers. With 70 km spacing, the system requires approximately 130 repeaters. Each additional repeater degrades OSNR and increases cost and potential failure points, so optimization is critical.

Given the extreme length, modulation format selection becomes crucial. DP-QPSK provides better OSNR tolerance than higher-order formats, enabling error-free transmission over the full distance. Per-channel capacity might be limited to 100-150 Gbps, but with 96 channels and 8 fiber pairs, total system capacity still reaches 75-115 terabits.

The power budget is extreme. With 130 repeaters each consuming 30 watts, total system power approaches 4,000 watts. This requires high-voltage power feed equipment capable of delivering over 13,000 volts while maintaining electrical isolation. Thermal management in repeaters is simplified by deep ocean temperatures near 1-2°C providing excellent heat sinking.

Lessons from Field Experience

Decades of operational experience have validated design approaches and identified areas for improvement. Pump laser reliability has proven excellent, with field data matching or exceeding predictions from accelerated testing. Modern pump designs show degradation rates well within acceptable limits over 25-year lifetimes.

Cable faults occur primarily from external events rather than equipment failures. Ship anchors, fishing gear, submarine landslides, and turbidity currents cause the majority of cable cuts. Repeater failures are rare, testament to rigorous reliability engineering and component qualification.

When failures do occur, the supervisory system and OTDR enable rapid fault localization. Cable ships can be dispatched with precise coordinates, reducing repair time and cost. Modern repair techniques allow cable recovery from depths exceeding 6,000 meters, though such deep repairs are challenging and expensive.

Continuous monitoring data reveals gradual degradation patterns. Pump laser currents slowly increase over years as diodes age, but remain within operational ranges. Fiber attenuation changes very slightly due to hydrogen ingression, but careful cable design minimizes this effect. Temperature variations on the seabed are remarkably small, typically less than 1°C annually, simplifying thermal management.

Future Outlook and Industry Trends

The undersea cable industry is experiencing rapid growth driven by insatiable demand for bandwidth. Tech giants are investing heavily in private cables, accounting for the majority of new installations. Annual investment in new submarine cables exceeds $3 billion globally.

Traffic demand is projected to grow at 30-50% annually through 2030, driven by video streaming, cloud computing, and emerging applications like virtual reality and artificial intelligence. This growth necessitates continuous innovation in repeater technology, amplifier design, modulation formats, and system architectures.

Sustainability is becoming a priority. Reducing power consumption lowers operational costs and environmental impact. Improved amplifier efficiency, optimized pump designs, and advanced power management enable greener systems while maintaining or improving performance.

The convergence of telecommunications and scientific sensing through SMART cables offers societal benefits beyond communications. Early warning systems for tsunamis and earthquakes could save lives. Climate monitoring supports better understanding of ocean dynamics and global warming impacts. This dual-use approach adds value while leveraging existing infrastructure investments.

Key Takeaways

10 Essential Points About Undersea Repeaters

- Critical Infrastructure: Undersea repeaters enable global internet connectivity, carrying over 99% of intercontinental data traffic across 1.3+ million kilometers of cable.

- 25-Year Lifetime: Repeaters must operate continuously for 25 years at depths up to 8,000 meters without maintenance, driving every design decision.

- EDFA Technology: Modern repeaters use erbium-doped fiber amplifiers that amplify optical signals directly without electrical conversion, enabling multi-terabit capacities.

- Typical Spacing: Repeaters are positioned every 60-100 km along cables to compensate for fiber attenuation of approximately 14 dB per span.

- Pump Redundancy: Multiple 980-nm pump lasers with shared pumping configurations ensure system survival even with multiple laser failures.

- Extreme Environment: Housings withstand pressures exceeding 800 atmospheres while maintaining thermal stability in near-freezing water temperatures of 1-5°C.

- OSNR Degradation: Amplified spontaneous emission noise accumulates linearly with repeater count, making noise figure optimization critical for ultra-long-haul systems.

- Advanced Architectures: Pump farming and space-division multiplexing with 16+ fiber pairs enable 500+ terabit system capacities.

- Supervisory Systems: Low-frequency modulation enables remote monitoring of amplifier performance, pump status, and fault detection via OTDR.

- Future Technologies: C+L band systems, SMART sensor integration, distributed Raman amplification, and AI optimization are driving next-generation capabilities.

For educational purposes in optical networking and DWDM systems

Note: This guide is based on industry standards, best practices, and real-world implementation experiences. Specific implementations may vary based on equipment vendors, network topology, and regulatory requirements. Always consult with qualified network engineers and follow vendor documentation for actual deployments.

Unlock Premium Content

Join over 400K+ optical network professionals worldwide. Access premium courses, advanced engineering tools, and exclusive industry insights.

Already have an account? Log in here