HomePosts tagged “Signal transmission”

Signal transmission

Showing 1 - 2 of 2 results

When we talk about the internet and data, what often comes to mind are the speeds and how quickly we...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

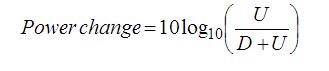

Power Change during add/remove of channels on filters The power change can be quantified as the ratio between the number...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

Explore Articles

Filter Articles

ResetExplore Courses

Tags

automation

ber

Chromatic Dispersion

coherent optical transmission

Data transmission

DWDM

edfa

EDFAs

Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers

fec

Fiber optics

Fiber optic technology

Forward Error Correction

Latency

modulation

network automation

network management

Network performance

noise figure

optical

optical amplifiers

optical automation

Optical communication

Optical fiber

Optical network

optical network automation

optical networking

Optical networks

Optical performance

Optical signal-to-noise ratio

Optical transport network

OSNR

OTN

Q-factor

Raman Amplifier

SDH

Signal integrity

Signal quality

Slider

submarine

submarine cable systems

submarine communication

submarine optical networking

Telecommunications

Ticker