HomePosts tagged “Optical receivers”

Optical receivers

Showing 1 - 2 of 2 results

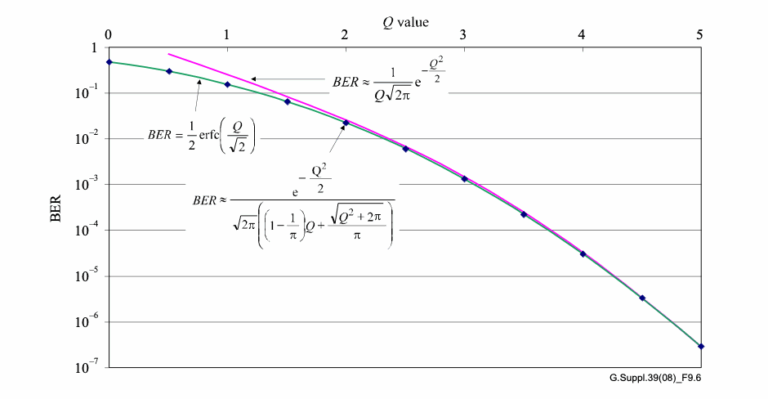

Signal integrity is the cornerstone of effective fiber optic communication. In this sphere, two metrics stand paramount: Bit Error Ratio...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

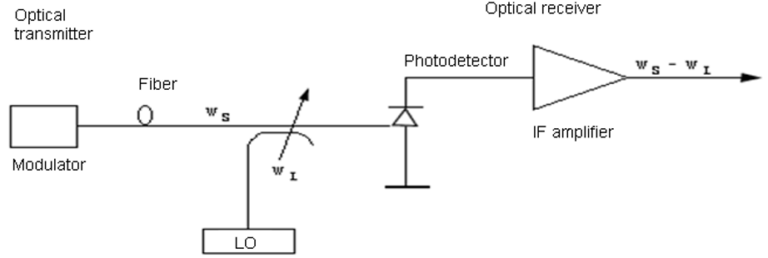

As we know that either homodyne or heterodyne detection can be used to convert the received optical signal into an electrical form. In the...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

Explore Articles

Filter Articles

ResetExplore Courses

Tags

automation

ber

Chromatic Dispersion

coherent optical transmission

Data transmission

DWDM

edfa

EDFAs

Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers

fec

Fiber optics

Fiber optic technology

Forward Error Correction

Latency

modulation

network automation

network management

Network performance

noise figure

optical

optical amplifiers

optical automation

Optical communication

Optical fiber

Optical network

optical network automation

optical networking

Optical networks

Optical performance

Optical signal-to-noise ratio

Optical transport network

OSNR

OTN

Q-factor

Raman Amplifier

SDH

Signal amplification

Signal integrity

Signal quality

Slider

submarine

submarine communication

submarine optical networking

Telecommunications

Ticker