HomePosts tagged “Data Centers”

Data Centers

Showing 1 - 2 of 2 results

The world of optical communication is undergoing a transformation with the introduction of Hollow Core Fiber (HCF) technology. This revolutionary...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

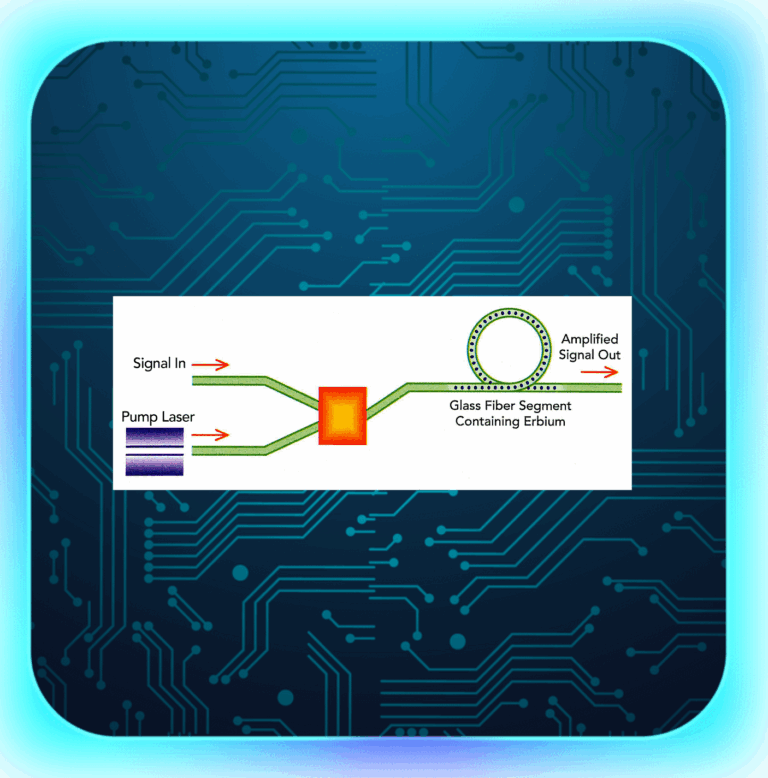

Optical Amplifiers (OAs) are key parts of today’s communication world. They help send data under the sea, land and even...

-

Free

-

March 26, 2025

Explore Articles

Filter Articles

ResetExplore Courses

Tags

automation

ber

Chromatic Dispersion

coherent optical transmission

Data transmission

DWDM

edfa

EDFAs

Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers

fec

Fiber optics

Fiber optic technology

Forward Error Correction

Latency

modulation

network automation

network management

Network performance

noise figure

optical

optical amplifiers

optical automation

Optical communication

Optical fiber

Optical network

optical network automation

optical networking

Optical networks

Optical performance

Optical signal-to-noise ratio

Optical transport network

OSNR

OTN

Q-factor

Raman Amplifier

SDH

Signal amplification

Signal integrity

Signal quality

Slider

submarine

submarine communication

submarine optical networking

Telecommunications

Ticker